Chinese-British relations

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Britain admired China and the Qing empire as a civilisation leading in art, philosophy and culture – although this admiration came through a lens of orientalism and exoticism.

By the mid-nineteenth century, however, the Opium Wars had shifted the British perception of China, Chinese peoples and Chinese commodities. British politicians declared that the Qing empire was against ‘free-trade’ and that it, and its commodities, should be treated with suspicion. By this point in time, however, Britain was a mass consumer of Chinese tea and demand was increasing.

Tea in Britain before the Opium Wars

Tea was introduced to Britain in the mid-seventeenth century, initially dubbed “China drink”.

It was popularised by Catherine of Braganza, of Portugal, after her marriage to Charles II in 1662. Her wedding dowry included a chest of Chinese tea as well as British control of Mumbai (then Bombay), India.

Tea was a symbol of Chinese exoticism – to have this expensive drink was a signifier of wealth and high social standing. As such, tea was quickly embraced by nobility, along with ‘eastern’ aesthetics and tea-wares that mimicked Chinese tea culture.

In 1750, the tax on tea was lowered, making it much more affordable and accessible. As an energising, easy to brew hot drink, tea’s popularity skyrocketed, becoming a daily necessity across homes in Britain.

Chinese tea and the crisis of British identity

The emerging reliance on Chinese tea as a pick-me-up, a domestic ritual, and cheap fuel for workers was at odds with the anti-Chinese propaganda being spread within Britain in the mid-nineteenth century.

Britain’s national drink could not be from a nation that was outside of its control, let alone from a nation that it was in conflict with.

A boycott of tea in response to the conflict with China would have caused a massive loss in profits. Plus, European merchants at the time did not actually know how tea was cultivated and processed.

In light of this, tea needed to undergo a metamorphosis from a Chinese drink to a British one. It needed a rebrand that plucked it away from its roots.

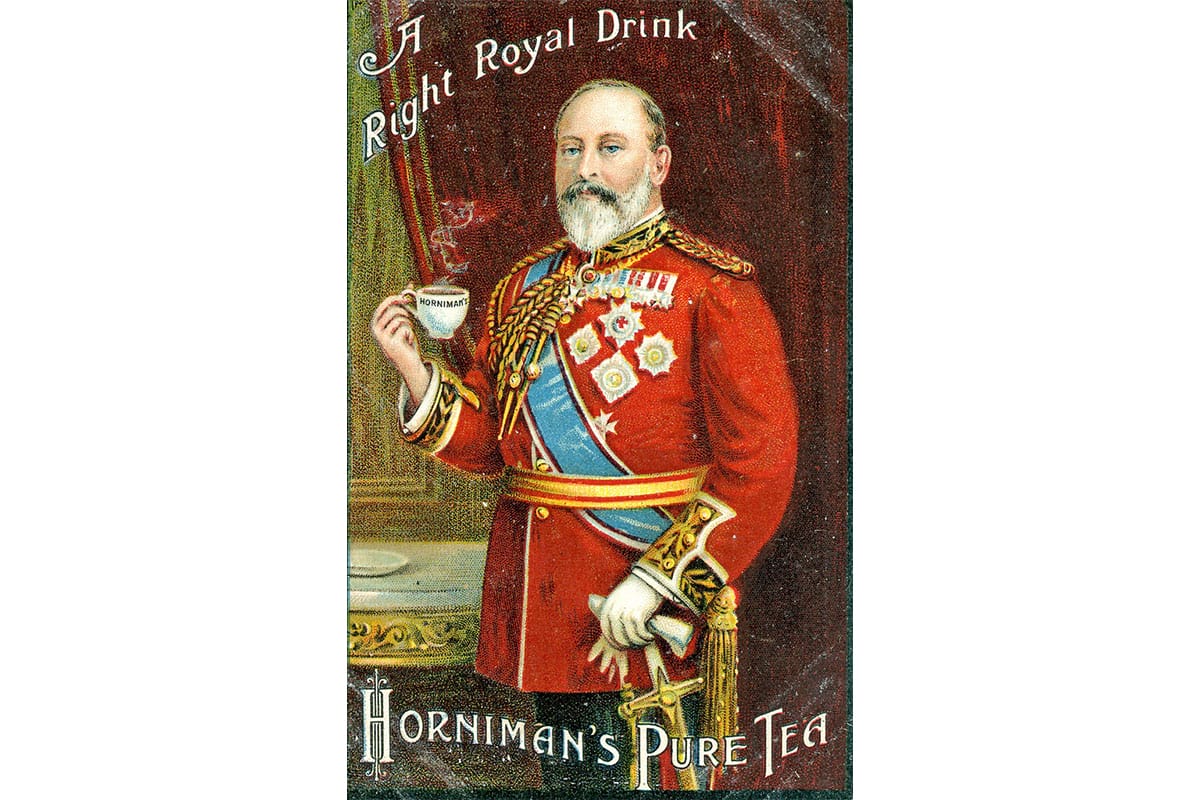

These examples of tea packaging and marketing materials from the Horniman collection exemplify these attempts to undermine Chinese tea culture and history.

Robert Fortune and the dyeing of tea in Britain

In 1846, Scottish botanist Robert Fortune stole and illegally smuggled tea plants and tea growers from China to India. Under the pay of the East India Company, the aim was to learn how tea was cultivated and processed.

Fortune reported that teas destined for Britain were dyed, fuelling the belief that Chinese tea suppliers were slowly poisoning Britain’s masses. In fact, East India Company merchants had been aware of this since, at least, the start of the nineteenth century.

The tea was dyed – to make it more appealing to British consumers who wanted their green tea to look green.

Fortune said that green tea was dyed with Prussian Blue and Gypsum, both made using chemicals that may cause illness or death in highly concentrated amounts or over a prolonged period. In fact, they were much more harmful to those dying the tea than to those ingesting it.

The marketing

Horniman’s Pure Tea was founded in 1826 by John Horniman. Horniman’s Quaker beliefs were used in the marketing, along with guarantees that nothing had been added to their pre-packed tea. It was marketed as ‘pure’.

The prominent brand name shows Horniman taking ownership of the tea, allowing consumers to buy into the brand and its values. The illustration shows the harvesting and processing of the tea taking place in a small rural setting, suggesting it’s all done under the watchful eye of Horniman’s Tea Company. Finally, the packaging reinforces that the tea is ‘free of the usual injurious mineral facing powder’

Horniman’s Pure Tea reinforced sinophobic values that were present at the time, demonising Chinese people and practices as it sold and profited from a Chinese product.

Gender, domesticity, and class

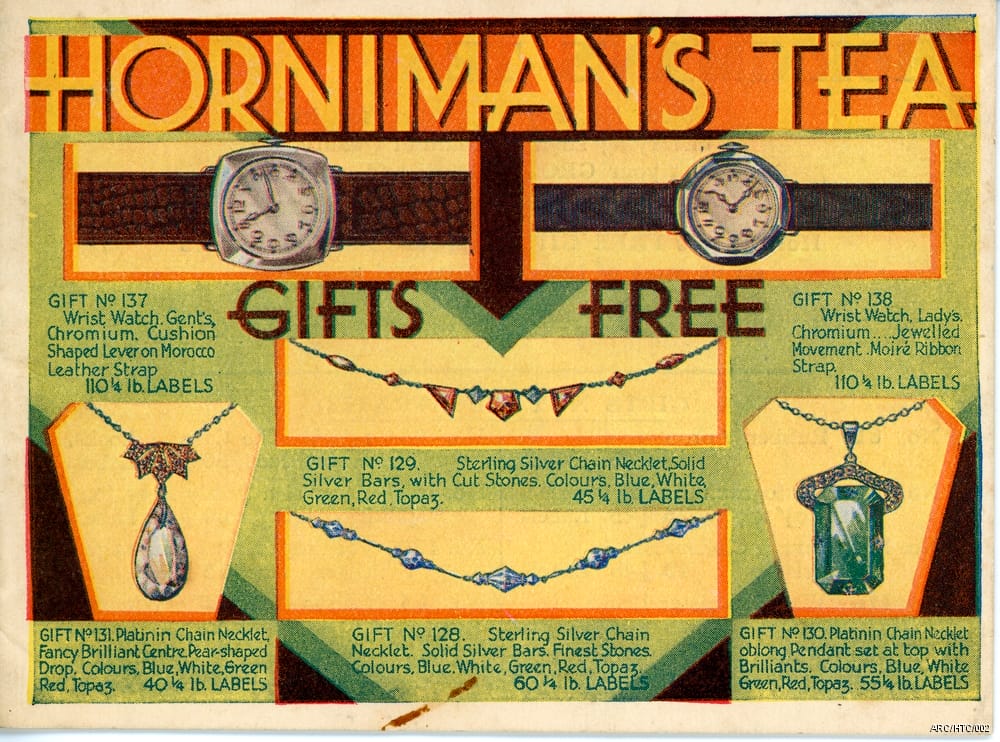

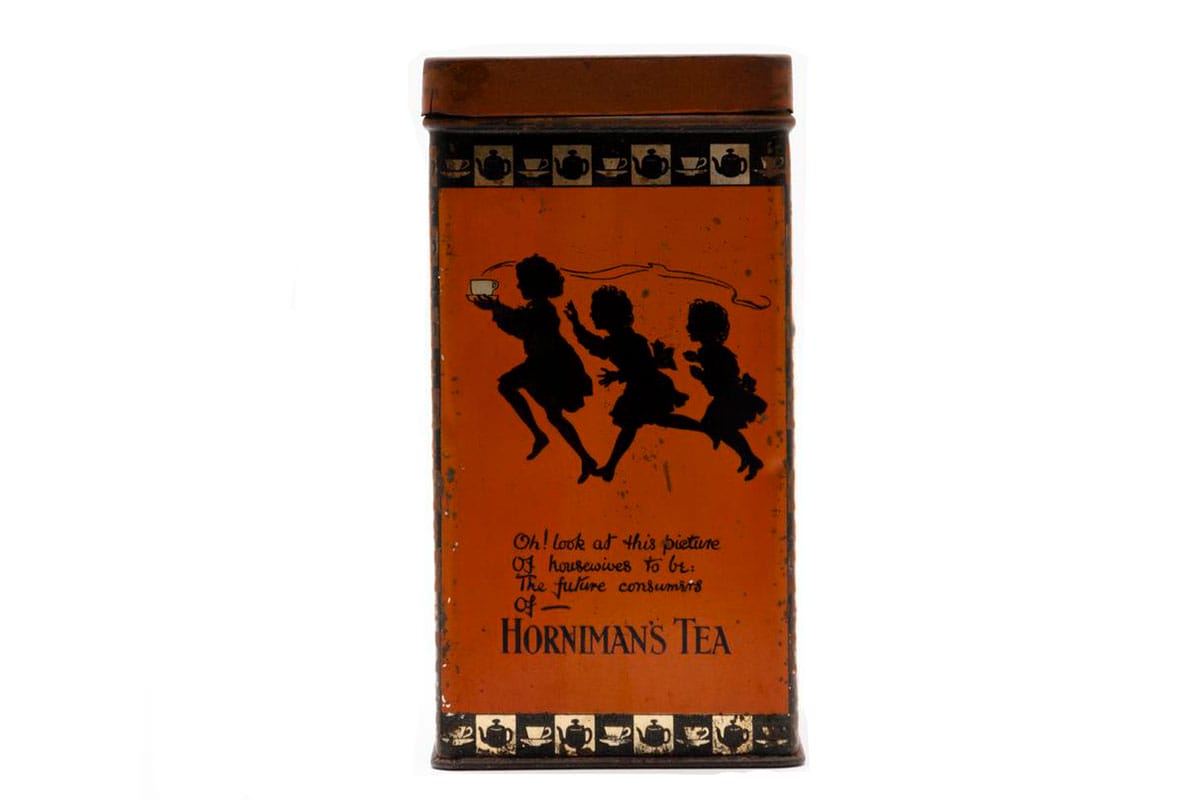

Another approach in the marketing of Chinese tea to a British audience was to align tea with British family and class values.

The emphasis was placed on how tea could improve the drinker’s life, as opposed to where it was from. Marketing often centred women from upper-class backgrounds enjoying tea with family or friends.

Horniman’s Pure Tea marketed itself as the go-to tea for the household. The company offered coupons and discounts for domestic items that might elevate your social standing. If someone bought enough tea, they could get discounted or free clothing, jewellery, cutlery and/or children’s toys.

By aligning tea with familial values and domesticity, it became a daily necessity that also held social value. That value however was no longer rooted in where the tea was from, but in the brand and what it seemed to represent.

The marketing

British tea marketing began featuring less, and in some cases no information, on where the tea was coming from. This enabled the erasure of Chinese tea heritage and culture for the British consumer.

‘British soil’ and empire

In 1788, Joseph Banks, the first director of Kew, suggested that the East India Company should cultivate tea plants in India.

From 1833 onwards Europeans were ‘allowed’ to ‘buy’ Indian land colonised by the East India Company. The first English tea garden in Assam was established in 1837.

In 1863, The Wastelands Act meant that Europeans could purchase ‘wasteland’ at cheap rates. As a result, large areas of Assam deemed ‘wasteland’ by European entrepreneurs and the colonial government were deforested to grow tea.

Tea was cultivated and produced through the labour of peoples in indentured servitude – meaning people were forced to work off debt that they incurred (for shelter, water) whilst living on the tea estates.

This exploitative practice was also used in Darjeeling; the south of India; Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) and later in the 19th century, Kenya, and East Africa.

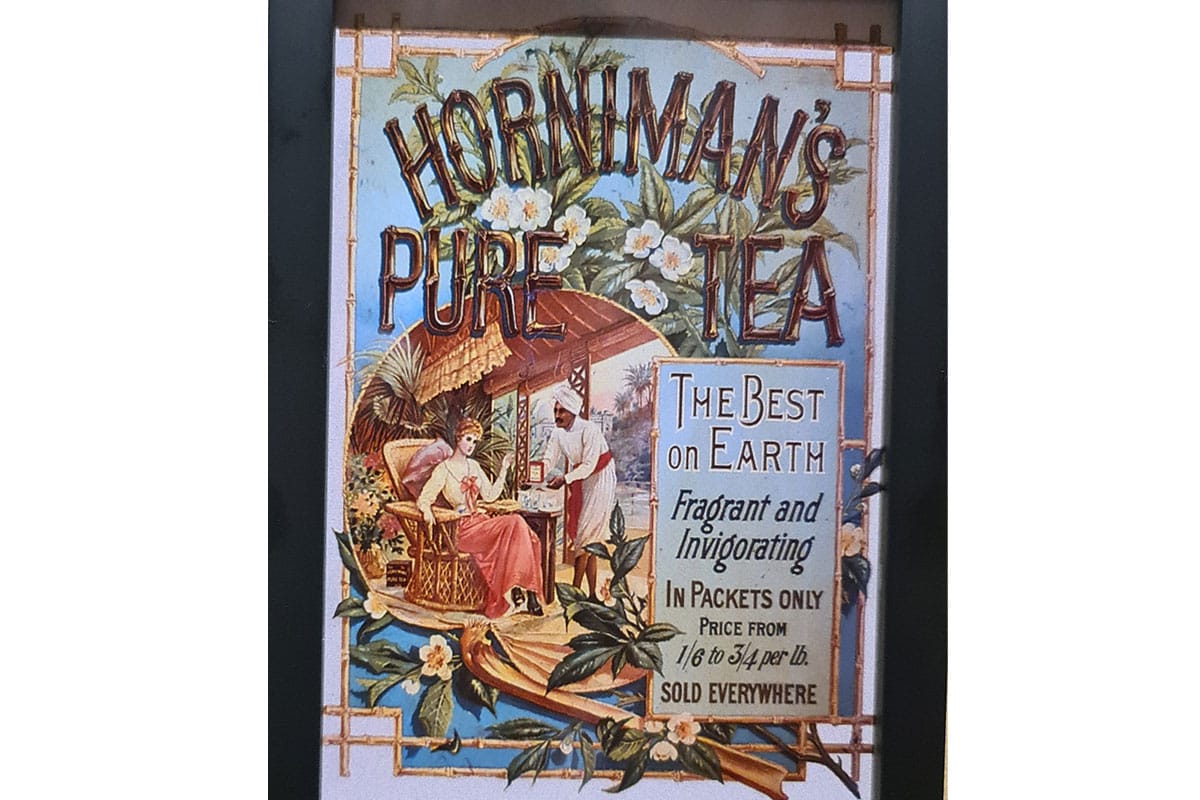

By the late 19th century, Indian tea was traded across Britain. The fact that the tea was from the British empire was a key point picked up by marketers. Indian tea, using racialised pseudo-science, was marketed as coming from ‘British soil’ and as being ‘superior’ to Chinese tea.

The British public were actively encouraged to buy goods from the empire and commodities grown on ‘British soil’. Describing the tea plantations of Assam and Darjeeling or Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) as ‘British soil’ vastly expanded the idea of Britishness.

The marketing

However, the portrayal of South Asian peoples in marketing reinforced ideas of British superiority. It maintained a clear hierarchy between the people in the United Kingdom and those who were in its empire.

When featured, South Asians were exoticised, typically shown picking tea in idyllic fields or serving tea. Notably, South Asians were not depicted consuming tea, or were rarely depicted in a location beyond the tea plantations, on marketing materials in Britain.

This reinforced imperial attitudes. The message to consumers was that South Asians were subservient to the British public. The tea was picked by Indian or Sri Lankan people for the drinker at ‘home’.

The portrayal of a woman, wearing a sari, picking a single tealeaf in the tranquil tea plantation was particularly popular. This imagery aided the romanticisation of Darjeeling, Assam and ‘Ceylon’ tea that continues to exist today. It helped establish a new exoticised tea heritage rooted in British colonial India that would overtake high quality Chinese teas in Britain.

Although these examples offer us an insight into just one organisation, the approaches taken by the Horniman Tea Company were widely used by many other tea brands. It presents us with a time when Britain was trying to reaffirm its national identity amidst a huge change brought on globalisation and imperial expansion.

The erasure of cultural heritage, and the propagation of racist ideas during this period has a legacy that continues to disproportionately impact East, South East and South Asian communities today.

The process undertaken by Horniman’s Tea Company and other tea brands at the time not only ingrained tea into ‘British values’ but also uprooted it from its Chinese origins. The relationship between manufacturing, the people who produce our goods and the consumer was broken.

This broken relationship continues today – how much do we know about the tea we drink? Where does your tea come from? What does your tea’s packaging tell you?