Where did the steel pan originate?

The steel pan is the national instrument of Trinidad and Tobago.

Enslaved people were not allowed to attend Trinidad and Tobago’s yearly carnival celebrations, which at the time were derived from European Christian traditions and similar to a harvest festival.

When slavery was abolished in Trinidad and Tobago in 1838, emancipated slaves were no longer barred from taking part. This included Canboulay processions, where burning sugar cane was carried to commemorate the harvesting of burnt cane fields during slavery.

The British Colonial authorities did not like Canboulay and the growing carnival celebrations. Captain Arthur Baker, the head of Trinidad’s police force, wanted to put a stop to it altogether. The early 1880s saw riots break out during Canboulay as police attempted to put restrictions in place. One incident saw British Colonial police open fire on the crowd.

In the 1880s and 1890s drumming was banned at carnival, as were tamboo bamboo, tunable bamboo sticks played by being hit on the ground.

This tradition of percussion instruments at celebrations continued to the 1930s, when the steel pan became increasingly popular. The pans were oil drums hit with bamboo sticks. The players discovered that the raised parts of the drums made a different sound to the flat parts.

Steel Pans first appeared on British TV on the Bal Creole show in 1950, thanks to Trinidadian creative Boscoe Holder and his Caribbean Dancers. This lead to the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO) performing at the Festival of Britain in 1951. The steel pan has remained a popular element of Carnival in Britain ever since.

In conversation: Dougie Dallaway

The Horniman’s Music Gallery has a tenor steel pan on display, originally from Trinidad and Tobago and created from an oil drum. It was presented to the Horniman in 1955, at a time when the two island state was under the colonial rule. This meant that the Horniman was able to order the drum from the Trinidad and Tobago Tourist Board.

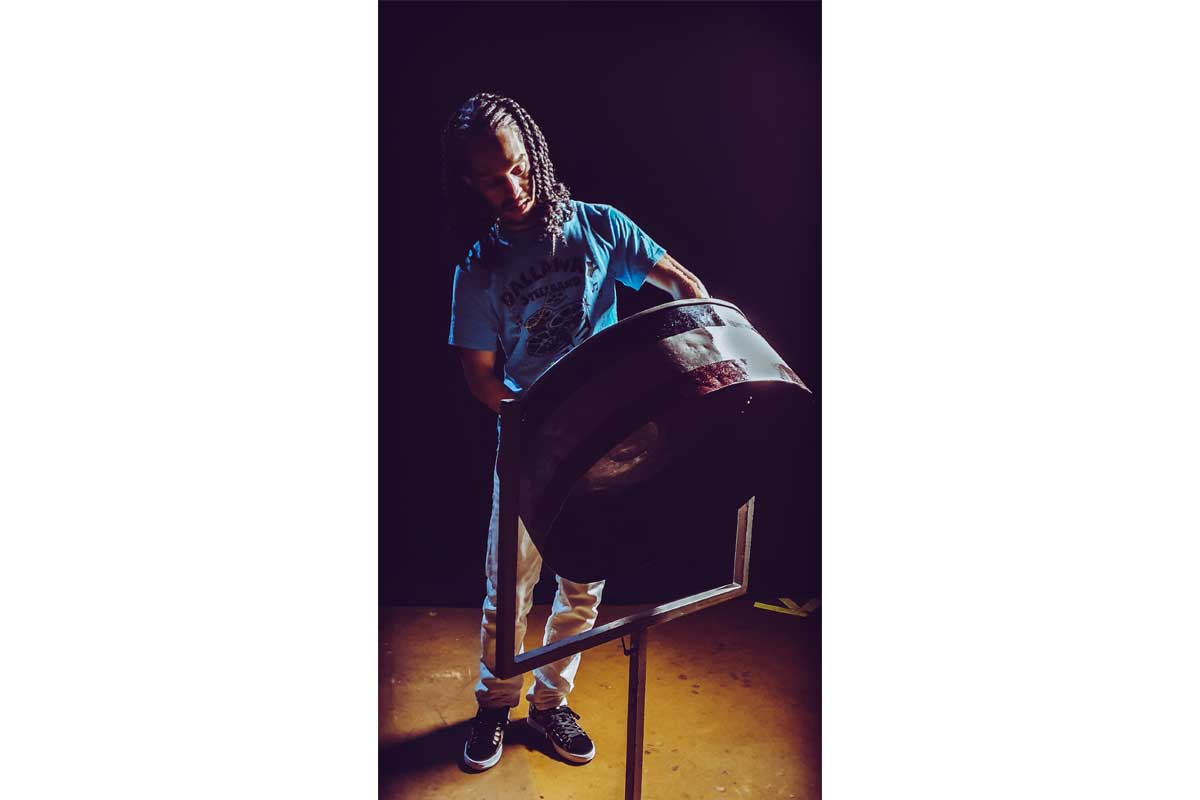

Dougie Swizz Dallaway, a renowned pannist, was invited to the Horniman to play our tenor steel pan as part of the 696 Project. He spoke with our Principal Curator of Musical Collections and Cultures, Margaret Birley and we’ve captured some of their conversation.

Dougie: ‘There was something about it that was very spiritual for me, I don’t know how long I was there for, I feel like I zoned out at some point. I could have been there for ten hours, two hours, it didn’t matter to me – I just feel like I really disappeared.’

But it wasn’t plain sailing from the off.

The pans, being so old, are very different to contemporary pans in their configuration. And although Dougie has played pans from all sorts of time periods, there was no way of knowing what these would be like ahead of his visit to us.

Dougie: ‘People have asked me to come in and play pans and I’ve thought – are they even gonna be playable? Do they know what they have? I’ve seen pans that were so smoothed over there were basically no notes in it.’

But luckily Dougie’s whole life is pan, and he made light work of establishing how the pans are played.

Margaret: ‘It was so impressive to see you find your way around the pans almost instantly, although they were so out of tune, and it was quite difficult to establish their real configuration and even which way up they were supposed to go – but you solved that instantly.’

111.241.22 Sets of gongs with divided surface sounding different pitches

Musical Instruments

But the pans themselves aren’t the only element here. The sticks, and the variations in rubbers, brought up a lot of debate and questions between Dougie and Margaret.

Dougie: ‘So originally they just used any sticks they could find really, because it was just about using anything you could find. It was very experimental in the beginning. They had shorter sticks, longer sticks, they just used to use wood that was straight up plain. They eventually evolved into the rubber.’

The rubbers that were first used were not like the ones that are used today. Today, you can buy sticks with pre-made rubber covers on, circular and thick, with a hole in the middle for the stick to go through. You can even buy rubber wraps, long thin bits of plastic that come in every colour imaginable. But originally, pannists would wrap their sticks themselves using found rubber – rubber which came from places like cricket bat wraps, or snorkelling goggles.

What difference does the rubber make?

Dougie: ‘When you hit wood, on the table, it’s quite hard sounding and you can hit the pan out of tune. But rubber, it’s more of a humble, less harsh sound.’

But wrapping the sticks yourself can be tricky, and is something that must be learnt over time.

Dougie: ‘In the pan world there’s a saying that only real musicians use wrapped sticks.’

With rubber that you wrap yourself you’re in control, as the player – you can choose the thickness, the weight, the distribution. It’s a tricky balance though.

‘If it gets too fat or too thick, the smaller notes on the pan are very difficult to bring out, so it becomes very difficult, you’re barely hearing the note at all. Whereas if the wrap is too thin when it comes to the bigger notes – it’s a similar thing they either can’t bring the note out, or you can’t hear anything at all, you end up hitting it out of tune whilst you’re playing it.’

Sticks have evolved over time to respond to changes in the pan themselves.

‘Originally all of the pans were single drums. The tenor was a single, like the ones you have; the bass is a single, the guitar is a single, the harmony is a single, all of them were just one pan that you’d put round your neck. You’d play that walking down the round, and you’d tap the side, for rhythm and play it at the same time.’

Dougie is going to continue gathering knowledge and information about pans for the Horniman, and work with Margaret to share all the knowledge he has gathered over a lifetime of pan.

Dougie: ‘My whole life is pan, everything I do is pan, I work it, I teach it, I do workshops online, I play pan, I do performances and I do try and educate as many people as possible once they’re interested. I grew up in several different places, but growing up in the UK there was a lot of ignorance from people that weren’t interested in it, who didn’t want to learn about it and took the mick out of it and there was a lot of racism and ignorance around it. So the fact that people wanna ask questions about it, I love that. For me it’s quite therapeutic.’

You can see the tenor steel pan on display in the Music Gallery.

Find out more about the 696 programme.