Hi Jane, first of all please can you tell us about yourself and your work?

I am inspired by the criminal, the cultural and the curious. The thread that runs through my practice is the desire to know why people do what they do. Or rather, did what they did.

A lifelong fascination with lesser-known aspects of social history, anthropology, museological presentation, surreal marriages of objects and thoughts, and the darker side of life incites my work.

As a perfectionist, I notice imperfection. I love the patina of age; the wear and tear that shows an object has lived a life, and my work will often deliberately emulate the aftermath of merciless insects or destructive people. The materials and techniques I use are largely determined by concept, and frequently turned on their head.

Most recently I have been producing work that addresses some of the history and hysteria associated with menopause for a solo exhibition that will commence touring later in 2022.

The Hair Receivers that you’ve created are based on actual objects that were used in the 19th Century. What drew you to hair receivers as objects?

Having made Shorn Out of Wedlock about five years earlier, I’d read quite a bit about the social history associated with hair, and hair receivers had lingered in my mind. Traditionally, these small lidded pots with a finger-sized hole were stuffed with the loose hair from brushing. This hair was then made into ‘ratts’ (potato-sized bundles stuffed, shaped and sewn into hairnets), and worn beneath the owner’s hair to create volume and height.

Someone then gifted me a box of human hair shortly after I moved into a new studio.

I had a shabby ebony hair receiver and was shown how to revive the wood. Satisfied to learn how to even up the quality of different types of ebony, I bought more pieces which I discovered were originally manufactured in component parts before being screwed together.

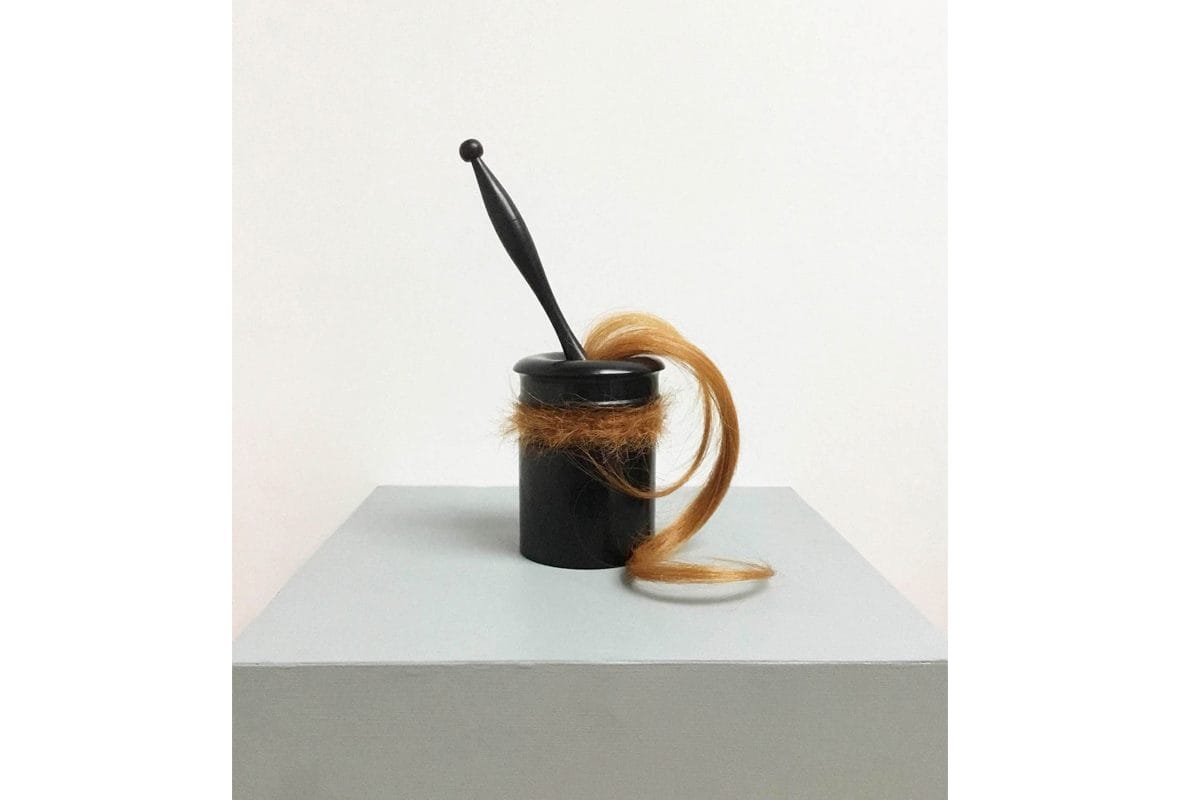

My Hair Receivers are fabricated from a melange of these unscrewed ebony pieces, formerly artefacts once common on dressing tables from the late-19th to mid-20th centuries: candlesticks, manicure stands, boxes, clock cases… I incorporated a length of auburn hair, liking its contrast against the blackness of the ebony.

The first piece I made is the tallest one, which later reminded me of an old-fashioned candlestick telephone, and the hair – which was sometimes neat, sometimes wild – brought to mind ectoplasm and tapped into the idea of spirit messages common in the same era. I pushed these multiple meanings further, reconfiguring the different components to appear as though they had always been just so.

In the Hair Receivers, hair is manipulated into different shapes. What is it like working with hair as a material and how does it differ from other, manmade, materials?

I have made quite a few pieces using hair, both human and man-made, the main difference being that human hair felts somewhat better. I use lots of different mediums and fabrication techniques in general, often inventing, rarely repeating.

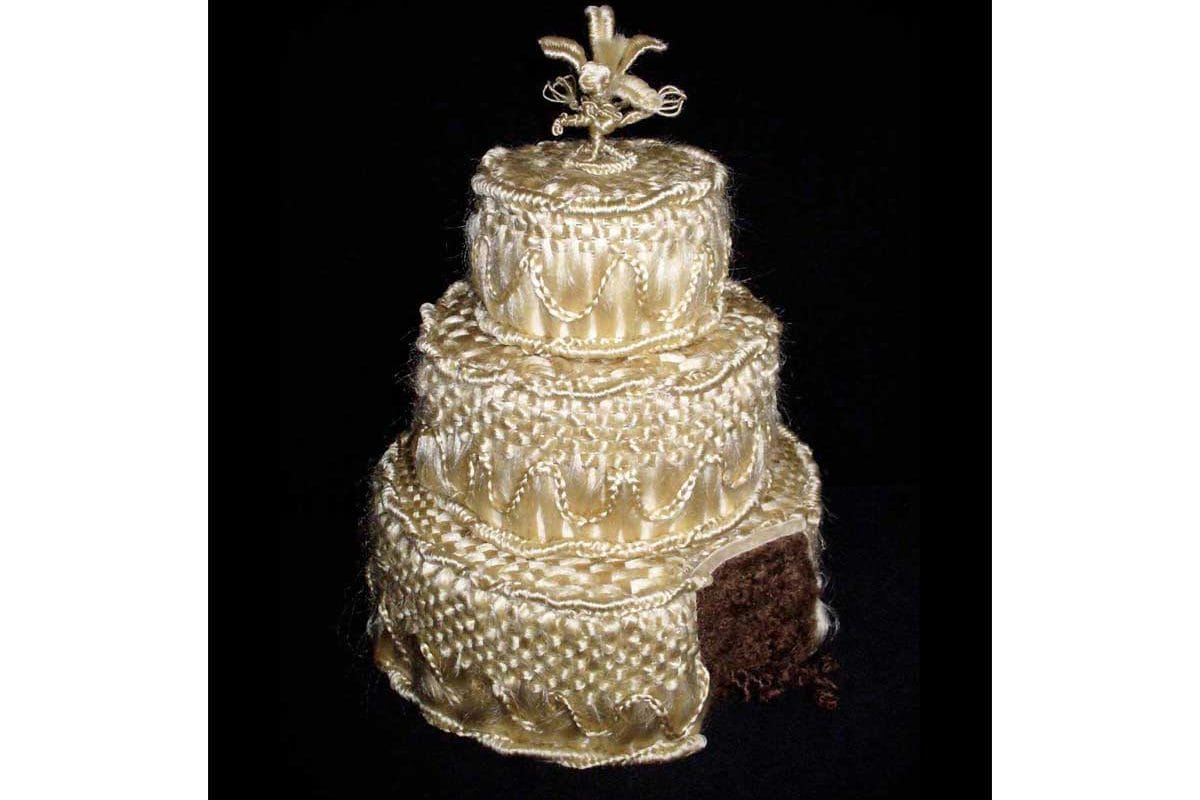

I improvised construction methods when making Shorn Out of Wedlock as working with long hair got really messy weaving, plaiting and stitching, and much ended up on the floor. Felting hair is less wasteful. I needle-felted a very large wall-hanging of a moth using about a dozen shades arranged in different pots like a paint palate, which enabled me to build up a more tonally graduated image.

Shorn Out of Wedlock looks at hair as a signifier of the marital status of women. Can you tell us more about the work and why you thought this aspect of hair was interesting?

During the 19th century, it was frowned upon for married women to let their hair flow free in public, this being normally reserved for single women, although they were allowed to wear it loose while mourning to show their distressed state.

Today, the potency of hair, long apparent in myth, literature and legend, is probably most evident via the religious resonance it retains in many faiths and cultures; delineating traditional male-female roles or marking the symbolic changes (of style or concealment) a girl makes after marriage.

Both the Hair Receivers and Shorn out of Wedlock look to the Victorians and their relationship with hair. What do you think it is about this era that meant people had such a complex relationship with hair?

The Victorians were obsessed with hair, embellishing its symbolism to often fetishistic levels, and generating new commercial values. From the mid-19th century onwards the codes and imagery associated with hairstyling grew in significance, and reflected the changing roles of women in society.

Queen Victoria’s highly publicised widowhood, and the short life expectancy of the age, also created a vogue for jewellery and artefacts made from the hair of the loved and lost.

See more on Jane’s website.

See Shorn Out of Wedlock and the Hair Receivers in Hair: Untold Stories