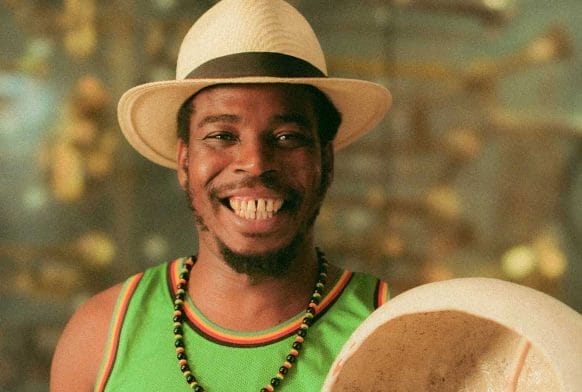

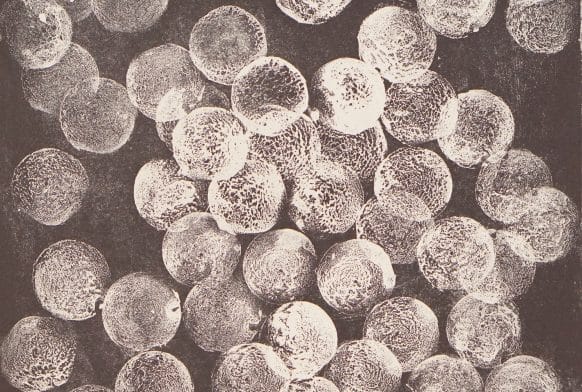

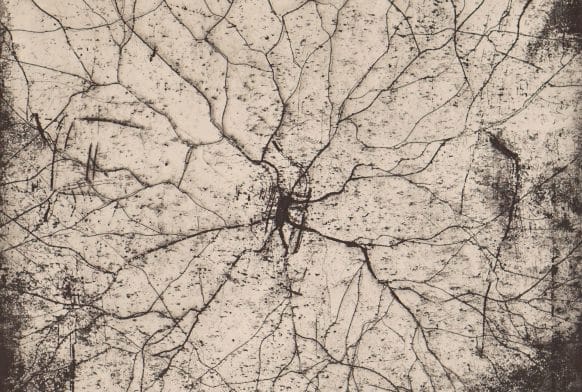

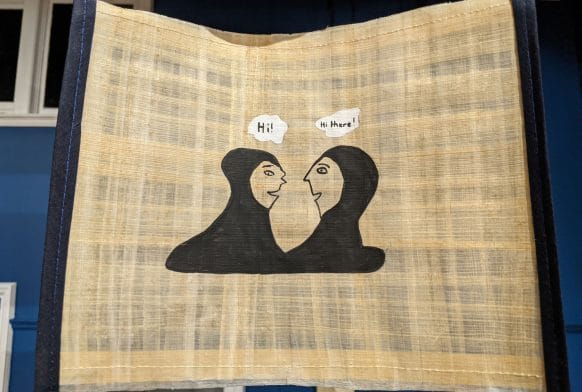

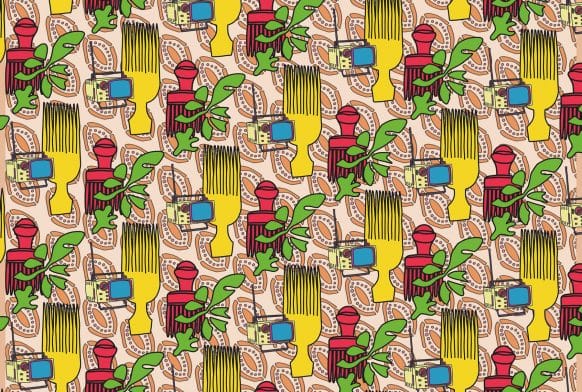

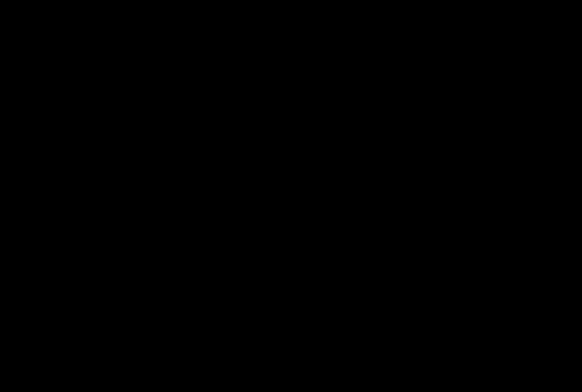

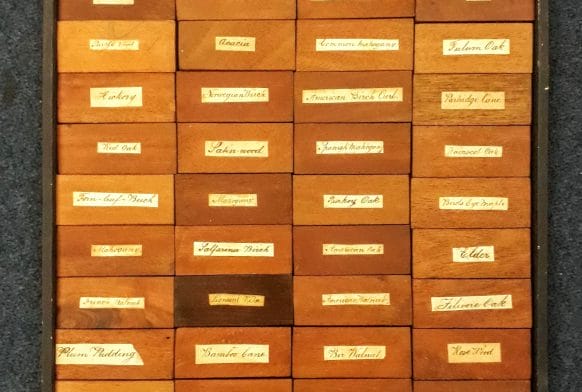

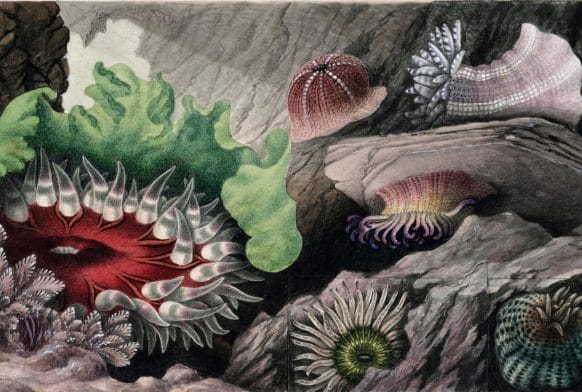

Light and dark brown geometric design.

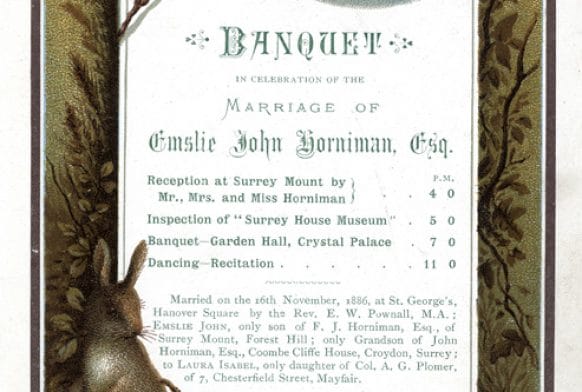

Barkcloth, Siapo Vala, Probably Savai‘i, Samoa, Western Polynesia While in other Polynesian island groups, everyone historically wore barkcloth (or tapa, as it is sometimes known in the Pacific) as a kilt or sarong, before 1800 in Samoa this was not the case. Only certain unmarried upper-class women were permitted this luxury, and so the cloth has retained an air of status and prestige about it. With the advent of Western clothing, fewer and fewer women make barkcloth in Samoa, and its production is now largely restricted to a small area of Savai‘i island. The Samoan method of making barkcloth (a felted, paper-like fabric) was much the same as that practiced throughout tropical Polynesia. The inner ‘bast’ layer of the bark from three-year-old saplings of the Paper Mulberry (u‘a, Broussonetia papyfera) was soaked in water and then beaten together by women into a continuous sheet using hardwood mallets (i‘e) on broad, table-like wooden anvils (tutua). Once complete, the fine white siapo cloth is decorated in a number of complex ways, using various techniques and a range of vegetable and mineral dyes. Hand-painted cloths were known as siapo mamanu, while the kind illustrated here is a siapo vala. Such cloths were given a dry-brushed stain of vegetable dye using carved wooden pattern-boards called ‘upeti, and then overpainted by hand in a second colour, or a darker shade, to highlight certain parts of the design. These boards were valuable commodities, and the number of boards used in decorating a siapo vala was a mark of the cloth’s value. We can see that two ‘upeti have been used to make up this cloth, creating an attractive composition in combination with multiple layers of painting. Barkcloth, pigments. 1960s. Presented to the Horniman Museum in 1971 by the Congregational Council for World Missions.