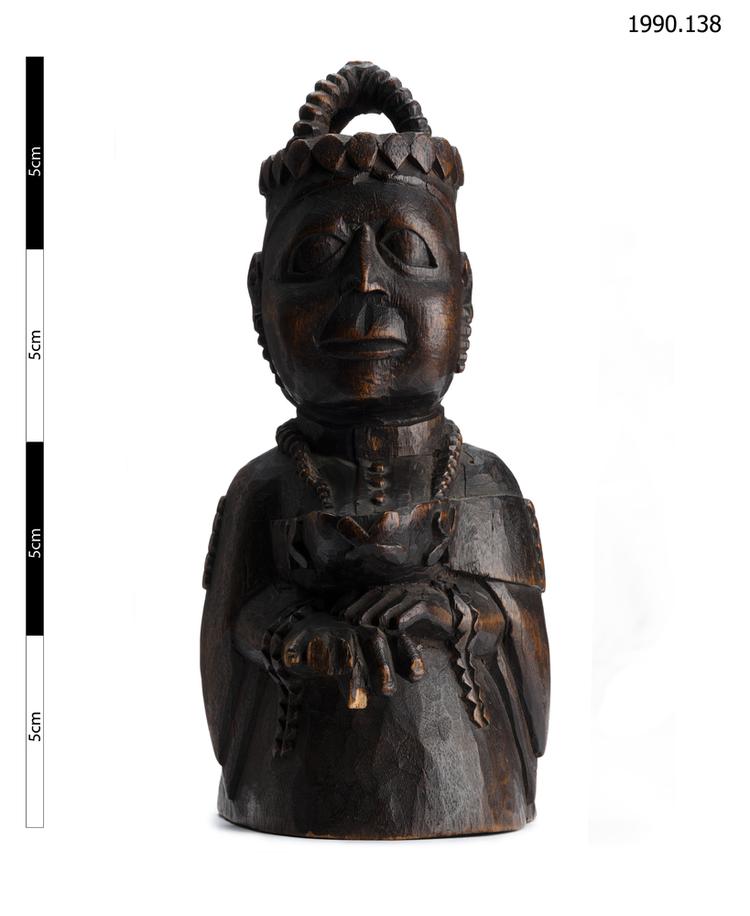

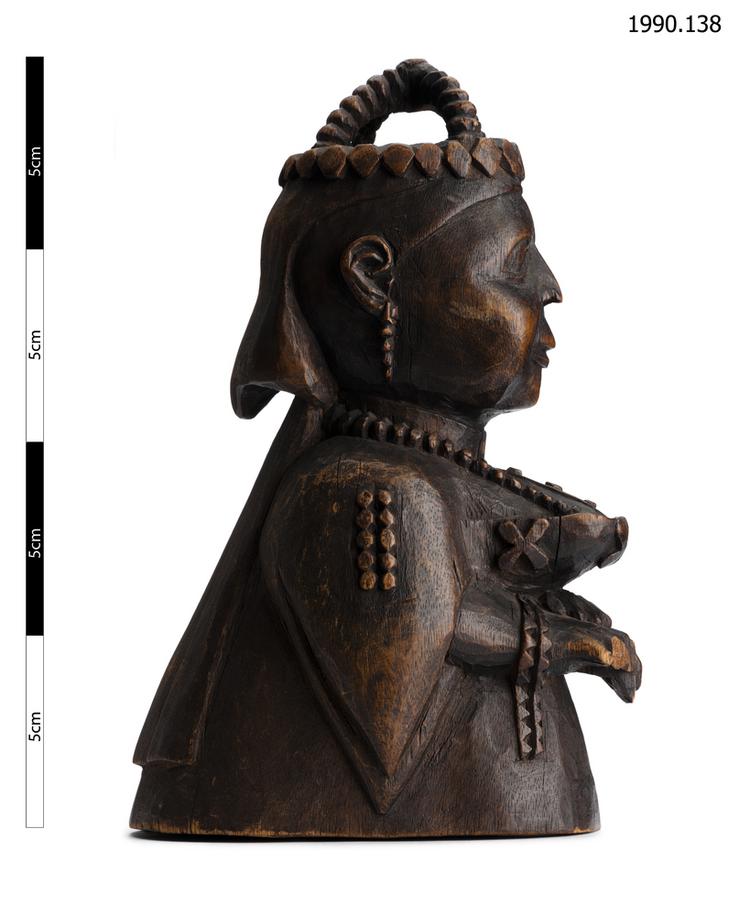

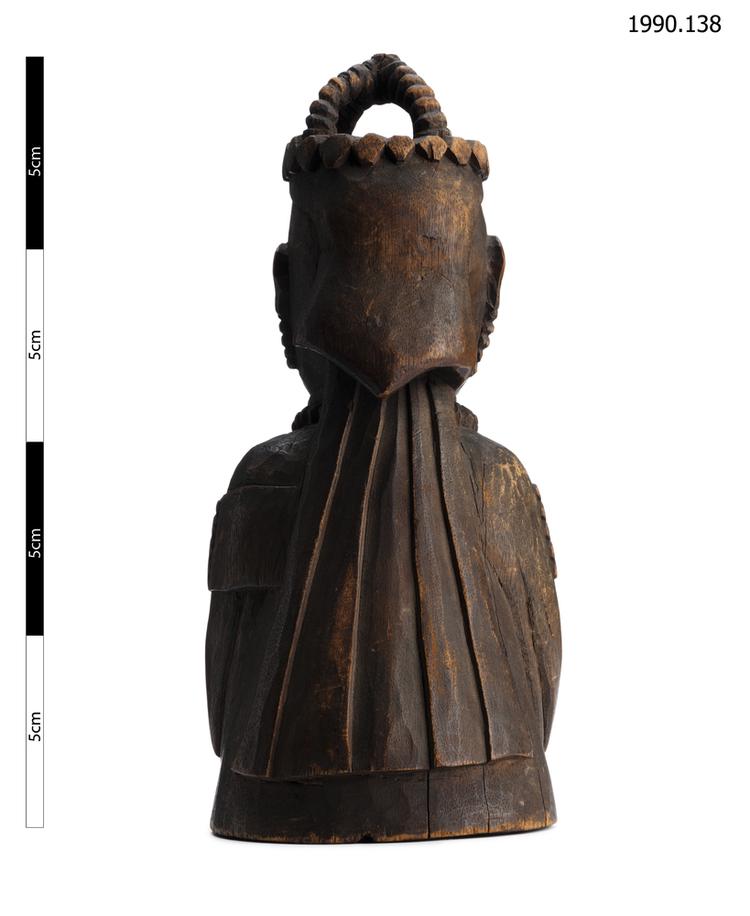

Carved wooden figure of Queen Victoria in regal dress. The figure is very detailed, and has feet carved underneath the skirt.

This well-observed portrait figure of Queen Victoria would have been made during her life time, probably from photographs of her distributed at the time of her Golden (1887) or Diamond (1897) Jubilee. A number of similar figures exist in museum collections in Europe and the USA. There is no evidence that they served any function in indigenous Yoruba society in the late 19th century, and recent research by Zachary Kingdon suggests that their original owners were probably Saros settled mainly in Lagos and Abeokuta (Kingdon, Z. “The Queen as an Aku Woman? Reassessing ‘Yoruba’ Queen Victoria Portrait Figures” forthcoming). Saro was the Nigerian name given to immigrants from the Sierra Leone peninsula. These returnees were mostly 'Aku', or formerly captive Yoruba who were released at Freetown in the nineteenth century off slave ships intercepted by British naval cruisers. After being educated by missionaries in Sierra Leone, a number of them chose to return to their homeland, where many settled as traders in Lagos and Abeokuta, where they were known as Saro. Limited opportunities in Freetown encouraged later generations to migrate to ports and settlements all over West Africa, either as independent traders or to take up positions with European firms or with the British colonial administration. Although frequently disappointed by the way they were treated by British traders and officials, most Aku/Saro retained a reverence and affection for Queen Victoria. They also retained their new-found Christian identity and formed prominent urban communities with their churches, schools, and other institutions. Crucially, Saro continued to dress in European-style clothing. In the context of British imperial culture in West Africa, deficiency of clothing was equated with the 'primitive' state of Africans before colonisation, and provided part of the visual evidence of the Africans’ need for 'civilization'. So the fact that category one ‘Yoruba’ Queen Victoria figures are represented wearing an impressive array of regal clothing suggests that, apart from their possible function as material demonstrations of loyalty to the British monarch, the Queen Victoria portrait figures were probably invested with other significances by their Saro owners. In fact, their meaning as domestic furnishings was probably as markers of Saro identity, or rather, of Saro identification with the notion of British 'civilization'. The assertion of an elite or distinct 'civilized' identity may have been seen as especially important at the end of the 19th century in a place like Lagos, where two groups with related cultural origins but different histories, Akus/Saros and indigenous ‘Yoruba’, lived side by side, and when colonial officials were likely to classify all blacks alike as uncivilized 'natives'. Two other similar Queen Victoria portrait figures in museum collections (Musee du Quai Branly and the Royal Collection) are known to have come from Lagos in southwestern Nigeria. This figure was probably also made in Lagos, and is likely to have originally been commissioned by a Saro resident there.