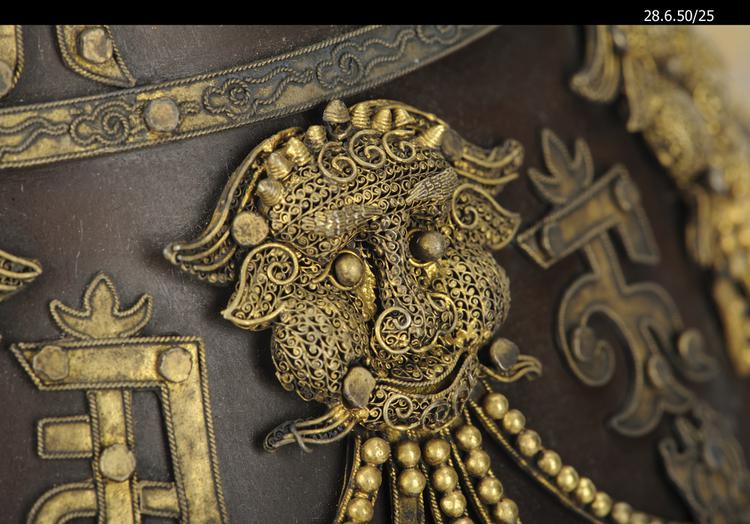

Ceremonial helmet. Conical helmet frame of lacquered brown wood with elaborate decorations in gold tacked onto the surface, including faces and dragons in filigree, stones in cloisonne settings, and script. The front has an elaborately decorated vertical peak, and a vertical gold bar above. The top has a pink finial on it, indicative of high rank. To the bottom of the helmet are attached padded fringes, pattern woven in gold thread with metal studs and edged in velvet; incorporated in this is a fastener round the neck, and also two holes for the ears.

This helmet probably dates from the late 18th or early 19th century. It would have been worn as part of an elaborate warrior’s costume by a courtier serving China’s Qing Dynasty. The decoration on the helmet is heavy with symbolism, drawing from both Chinese mythology and Buddhism. The helmet is surmounted by a finial of opaque pink glass, which is probably indicative of rank. The finial is capped with a plate bearing the Chinese shòu character, representative of long life. Dragons repeatedly occur in the helmet’s decoration. The dragon was associated with the emperor and today it continues to be the ultimate symbol of the cosmic energy qi and a powerful symbol of good fortune, it is also a symbol of power, virility, masculinity, and high rank. Several of the dragons on the helmet are depicted flanking flaming pearls, a motif which is very common in ceremonial helmets of this era. The pearl is symbolic of good luck and prosperity. The characters which run in bands around the helmet are of the Lantsa script, a calligraphic, official or religious script used in Nepal, Tibet, China, and in Buddhist contexts in India. They appear to spell out two of the fundamental Buddhist mantras in Sanskrit. The mantra, ‘Om Ma Ni Pe Me Hum’, is probably repeated in the first two rings of inscription. ‘Om Ma Ni Pe Me Hum’ is the most commonly recited of mantras in Tibetan Buddhism. It is associated with Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, of whom the Dali Lama is understood to be a reincarnation. Some authorities translate, ‘Om Ma Ni Pad Me Hum’ as, ‘Jewel in the lotus’. Interpretations and uses of ‘Om Ma Ni Pad Me Hum’ are manifold as it is argued that the mantra contains the essence of the entire teachings of the Buddha. The third ring, which has the largest characters bears the mantra, ‘Om Aa Hum’, translating to, ‘Body, Speech, Mind’. By reciting this mantra a practitioner works to purify all the negative actions he or she has committed through body, speech, or mind. The faces which separate out the middle row of characters represent the deity Kirtimukha (Glorious Face) in Sanskrit or T'ao t'ieh (Monster of Greed) in Chinese. Kirtimukha occurs as a popular motif in religious architecture across South Asia. The motif can be understood to symbolise a devotee’s absorption in worship. Much of the symbolism borne by this helmet points to power, prosperity, and good luck. But the incorporation of Buddhist mantras and symbols also suggests the warrior’s concern for protection during battle. This helmet, however, would never have seen armed conflict. The phenomenal amount of highly skilled work that went into its construction demonstrates the owner’s ability to command enormous resources. It is an item of costume designed to communicate high status in the elite environment of a Qing court, not a helmet to protect from a weapon’s blow. Although the helmet is clearly of Chinese manufacture, in the Horniman’s records it is attributed to Tibet. This attribution came with the helmet when it was donated by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1950. The Victoria and Albert Museum, then the South Kensington Museum, acquired the helmet from the dealer John Spark’s Ltd. in 1906. This date, combined with an attribution to Tibet, suggests that the helmet could have been collected during the Younghusband Campaign (1903 - 1904). Although the helmet is Chinese it may have found its way to Tibet as a high-level diplomatic gift to a Tibetan official, or as a donation to a Tibetan monastery. However, the records of John Spark do not mention the helmet in conjunction with Tibet (it was acquired in 1906 by the dealer with a group of five Chinese objects). The first association of the helmet with Tibet comes in a report from a South Kensington Museum curator written in 1910, which accurately describes the helmet, but misattributes it as Tibetan.