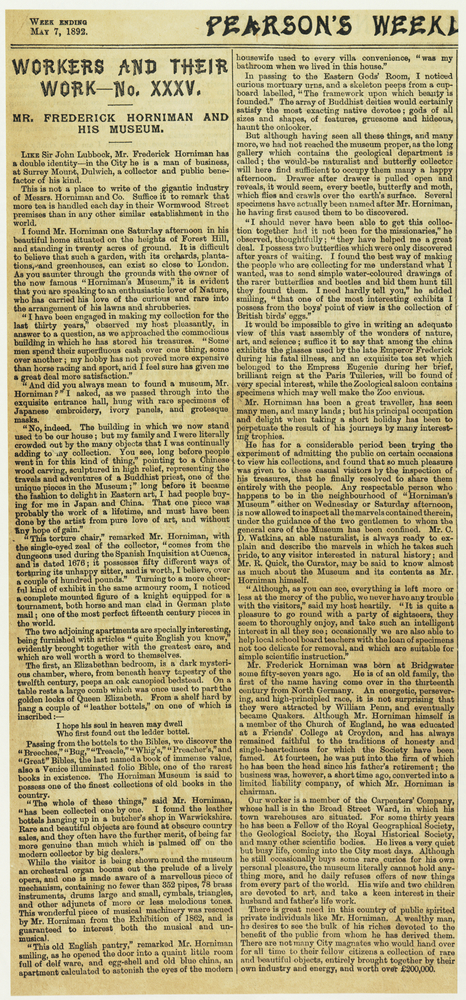

One newspaper article about Frederick Horniman’s Museum and his life, published in Pearson’s Weekly on May the 7th, 1892. The article follows a structure which combines interview with the description of the Museum and some biographical data.

The unknown journalist paid a visit to Frederick Horniman in his Forest Hill home one Saturday afternoon, and took this opportunity to both visit the Museum, and to ask his host some questions. The visitor was immediately impressed with the beauty of the Horniman home, and the twenty acres garden setting. As he and his host were approaching the building housing the Museum, Frederick Horniman remarked that he had been engaged in making this collection for the last thirty years. This was his hobby, not necessarily more expensive than horse racing or sports, but much more satisfying. He did not start collecting with the intent of founding a museum; the idea formed only when he and his family felt too crowded in their home by the artefacts, and consequently moved out to a new building and dedicated the space exclusively to the collections.

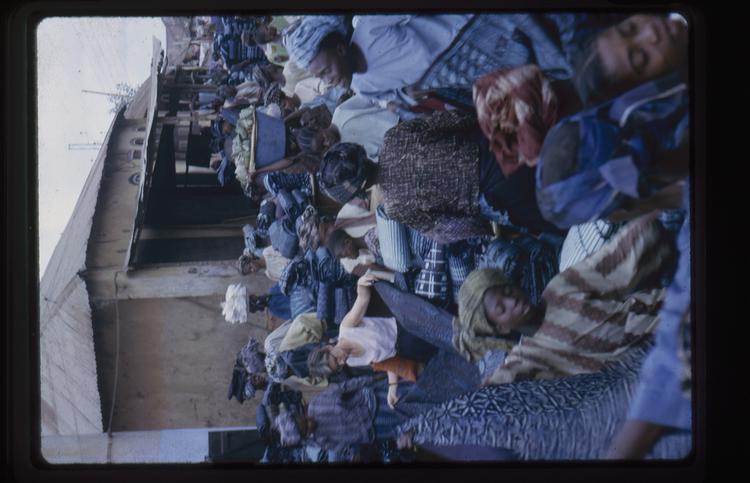

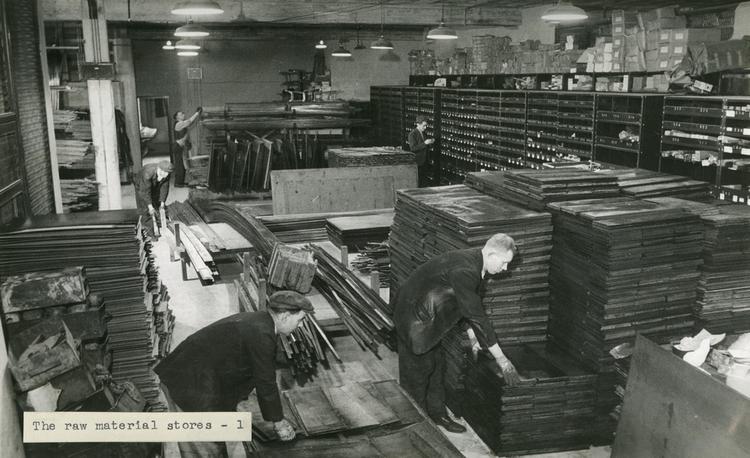

The visitor enjoyed a tour of the Horniman Museum guided by Frederick Horniman himself. While admiring the Oriental displays, the host remarked that he had started collecting Chinese and Japanese artefacts well before an interest in Eastern art would become fashionable in Europe. Of special interest to the visitor proved to be the Spanish Inquisition Torture chair, dating from 1676; the fifteen century German man and horse armour; the Elizabethan bedroom, with Queen Elizabeth’s comb resting on the table. The visitor marvelled at the Bible Room, especially when admiring the Venice illuminated folio Bible, one of the rarest books in existence; and was amazed by the skilfully played orchestral organ, the one saved by Frederick Horniman from the Exhibition of 1862. The old English pantry, or the Eastern Gods Room with its array of Buddhist deities, never failed to leave an impression. But only when they arrived at the long gallery containing the natural science collection had they reached the museum proper: drawer after drawer with every beetle, moth and butterfly known, some named after F. Horniman. Other special exhibits singled out by the visiting journalist were the collection of glasses used by the late Emperor Frederick, Empress Eugenie’s exquisite tea set, and the Zoological Saloon.

Frederick Horniman had been experimenting with having members of the general public admitted to visit his collections for quite some time. He found those instances quite instructive for the visitors, therefore he decided to have the Museum open free of charge every Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. Mr. C. D. Watkins, and able naturalist, and R. Quick, the Curator, would provide the guided tours. The Museum would even help local teachers with loaning them not too delicate specimens, for the purpose of classroom scientific instruction.

The biography of Frederick Horniman begins with him being born at Bridgwater in an old family of Quaker tradition. Although he himself opted for the Church of England, he was educated at the Friends’ College at Croydon, until joining his family business at fourteen. Frederick Horniman was, at the time of this article, fifty-eight years old and member in a wealth of scientific and professional bodies (such as Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, the Geological Society, the Royal Historical Society). Although he was still buying the occasional curiosity for his own pleasure, he was no longer purchasing artefacts for the museum because there was no more space for display or depositing. The Horniman Museum’s collection was estimated, at that time, at over £200.000 – a figure which, concludes the article’s author, not many businessmen would convert into art and science, and then dedicate the result entirely to the general public.