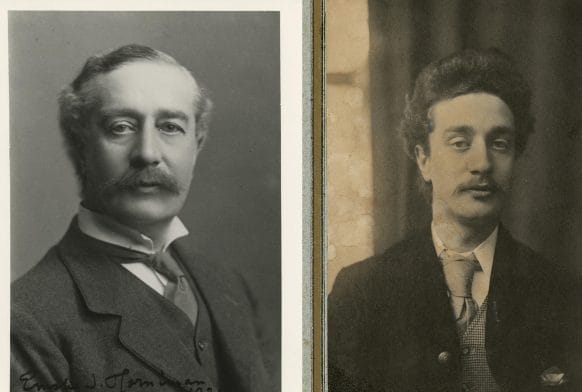

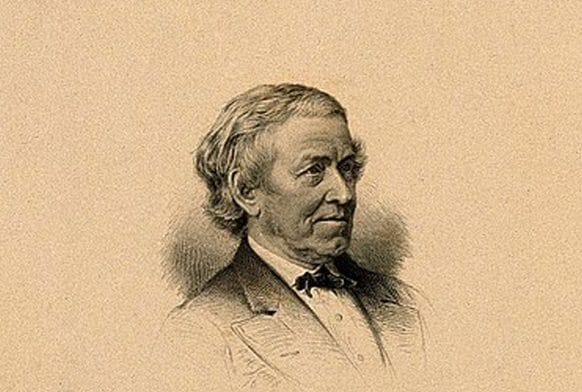

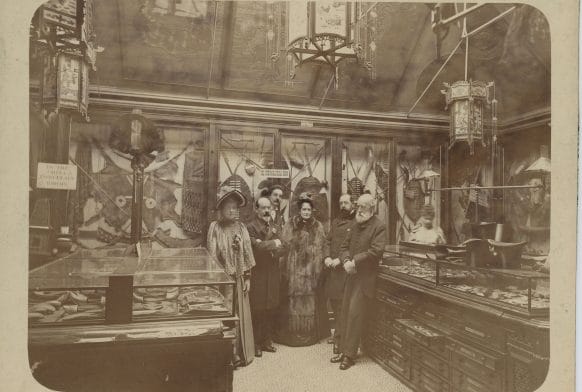

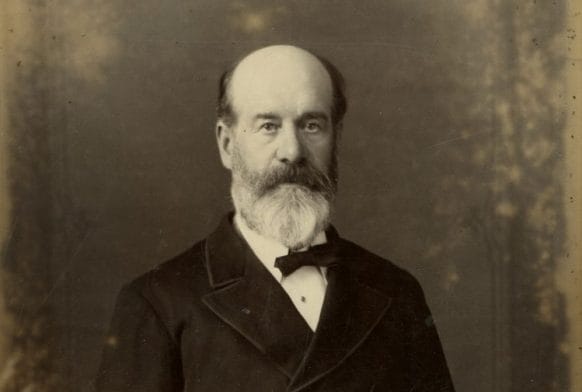

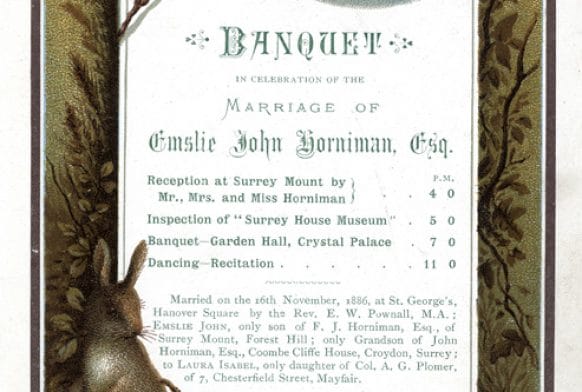

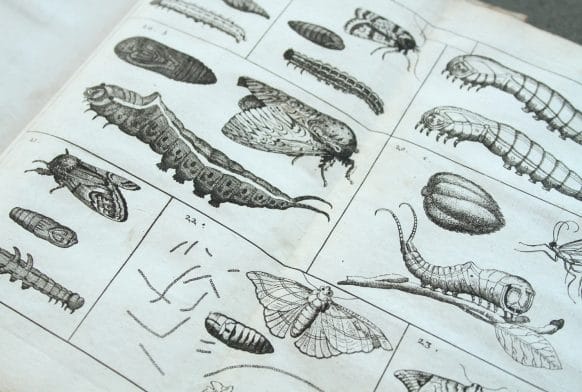

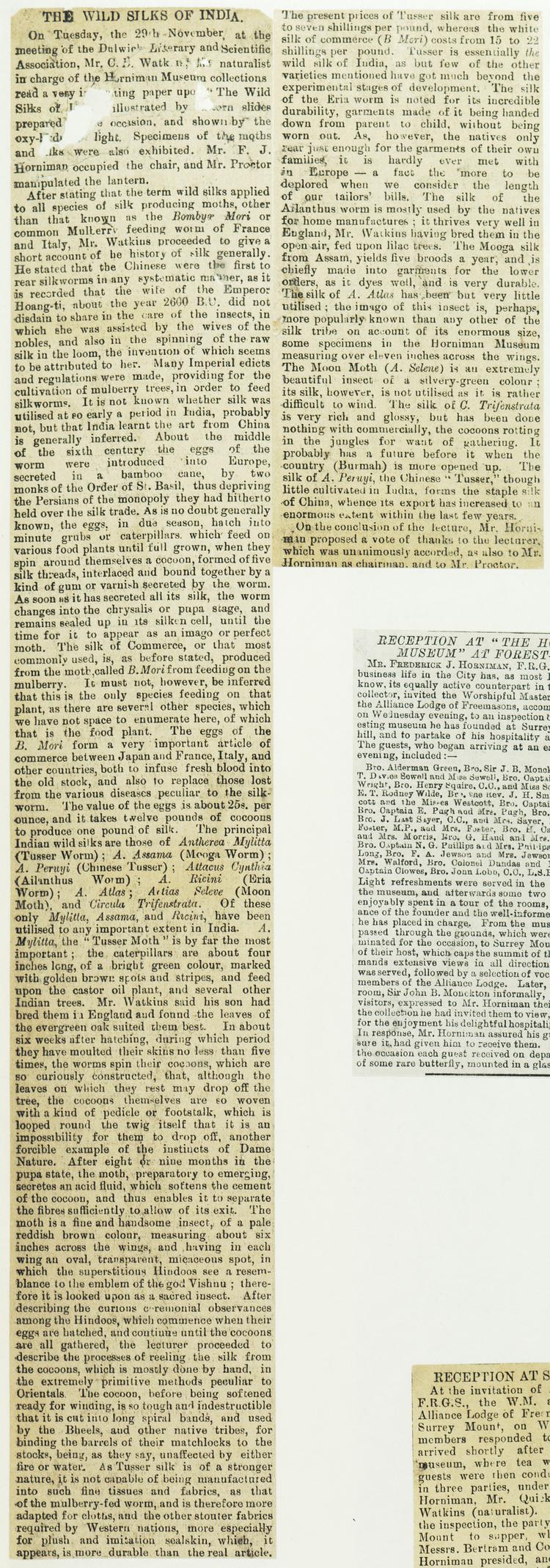

One newspaper article detailing the scientific information presented by C. D. Watkins, the Horniman Museum’s naturalist, on the 29th of October when he read a paper about moths and wild silks in front of Dulwich literary and Scientific Association. The presentation was illustrated by slides, as well as moths and silk specimens. F. J. Horniman was part of the audience.

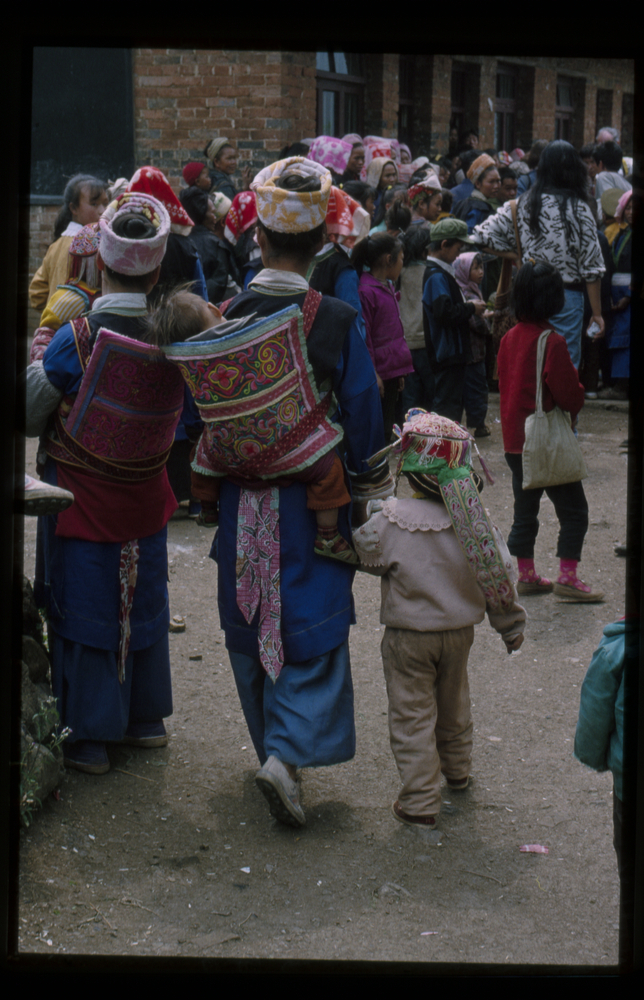

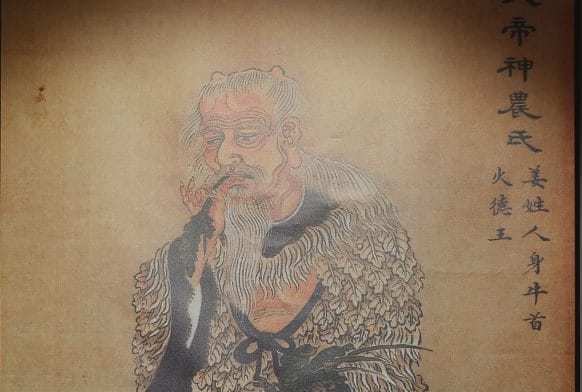

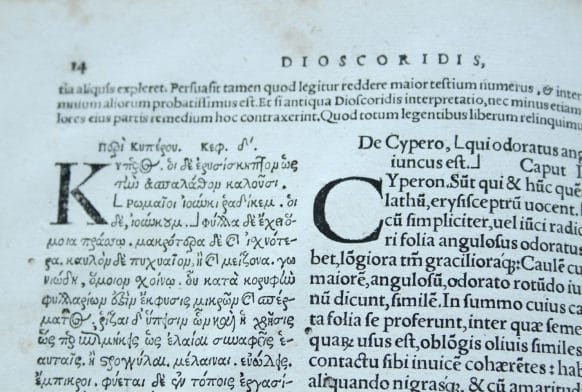

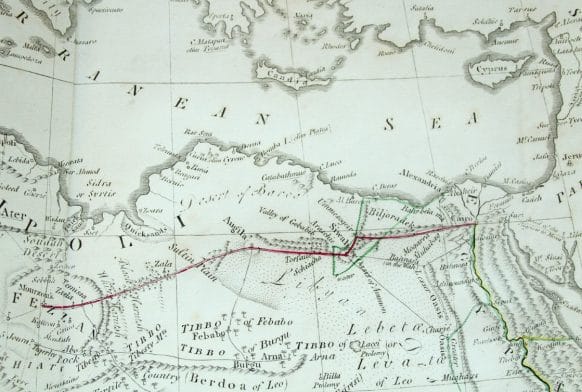

The guest reader started by familiarising the public with a bit of history concerning moths and silk production: the first to rear silkworms in any systematic manner were the Chinese, as early as 2600 B.C. It is generally inferred that India learnt this art from China later on. About the middle of the 6th century the eggs of the silkworm were introduced in Europe, hidden in a bamboo cane by two monks of the order of St. Basil. Thus, the Persians were deprived of the monopoly they had previously hold over the silk trade.

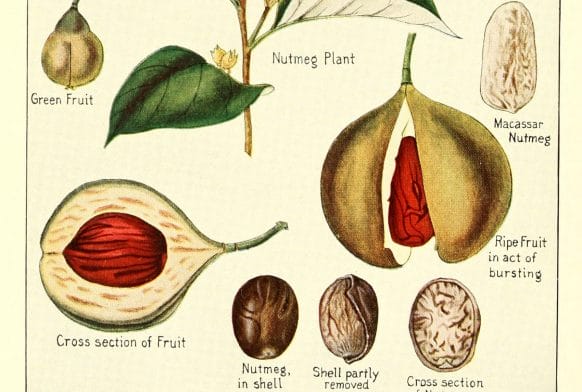

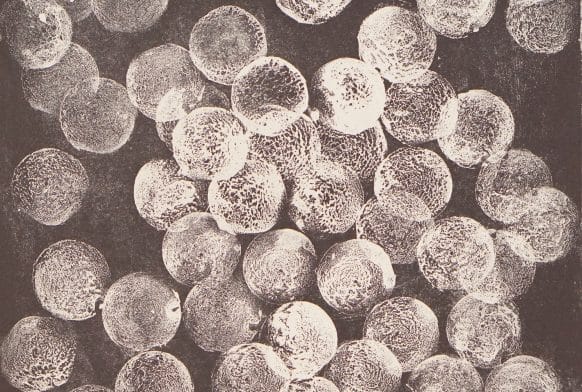

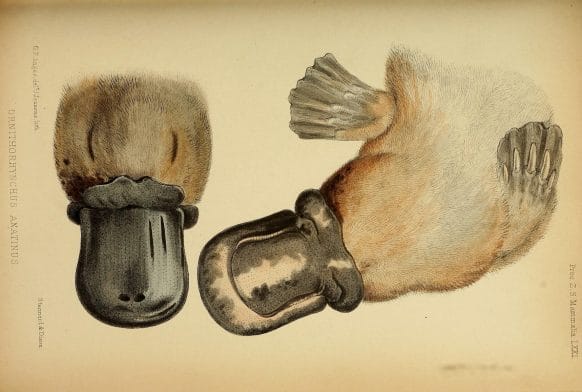

The most commonly used silk is that produced from the moth called B. Mori feeding on the mulberry. The eggs of the B. Mori form an important part of the trade between Japan and European countries such as France and Italy. It takes about twelve pounds of cocoons to produce one pound of silk.

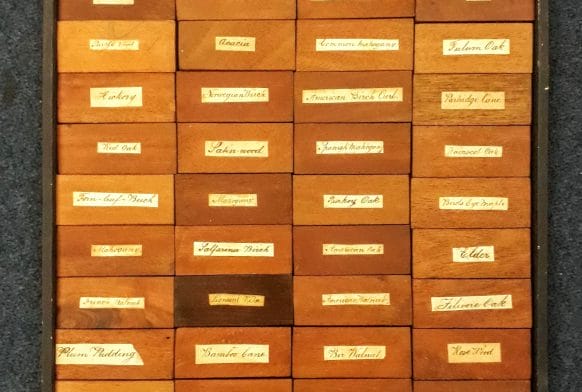

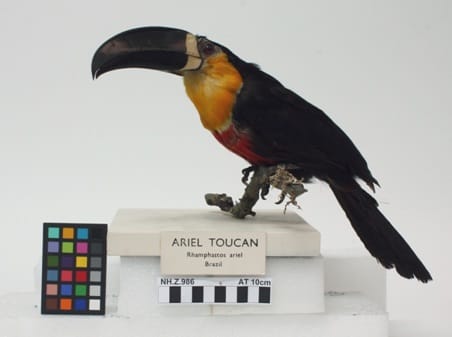

There are many varieties of silk worms in India, but only three of them have been used to any important extent. A. Mylitta, the “Tusser worm”, is by far the most important source of wild silk in India. Mr. Watkins said his son had successfully bred Tusser worms in England and found that the evergreen oak suits them best. Tusser silk is of a stronger nature and is not capable of being manufactured into the softer finer silks as that of the mulberry-fed worms; but it is the perfect silk for durable garments. The reader also discussed many other little-known species of wild silk worm, such as the Eria worm and the Ailanthus worm in India, or the Mooga silkworm from Assam: these are all species of silkworm used to some extent by local peoples, but largely unknown in Europe and yet untested for larger, commercial production.