Masquerade in Guyana

© Scherin Barlow MassayIntroduction

Muddah Sally as I remember her wore a long flowing dress. As a child, nothing could instil more fear me, than the sight of that gigantically, tall woman, swaying, her arms and toppling toward me. The way she moved petrified me. I thought that she was going to kill me. I thought that I was going to die.That was my earliest memory of masquerade in Guyana. Since then, whenever I see stilt walkers, a mixture of fear and fascination always grips me, as I am transported back to that giant figure. As a result of those memories, I decided to look at the origins of masquerade in Guyana.

In this essay, I will give an overview of masquerade. How it arrived in Barbados and how it was celebrated. The Crop Over festival, the characters, in both masquerades, I will look at eye-witness descriptions of masquerades in Guyana, the main characters in both types of masquerades, the instruments in the Guyanese masquerade and their origins. I will look at an eyewitness account of Afrikan masquerades, why it was celebrated there?

Masquerades/ Carnivals

Masquerades have always been part of the cultural traditions in many Afrikan societies. However, European ideology in trying to suppress Afrikan cultural references in the “New World” has resulted in the fragmentation of knowledge of the exact reasons why certain things were practised and by whom. Because of that suppression of Afrikan culture, many Afrikan-Caribbean’s cannot differentiate masquerade from carnival. Although the two elements are lumped together, the two celebrations had two very different beginnings and world views. But, despite the fact that masquerade had its inception before Christianity, the term carnival, is given the dominant emphasis as to its origins, with masquerade being relegated to just a component within the carnival.History of Carnivals

Carnival is celebrated throughout the Caribbean, in parts of England, the USA, Canada and mainland South America. While many view the carnival as one big procession of merrymaking, few stop to consider the different aspects that have come together under the umbrella of carnival.In England, the Notting Hill Carnival is celebrated by millions of revellers during the last bank holiday weekend of August. Some go to listen to the sound systems; a relatively new component to the carnival. Others follow floats with steel-bands; the invention of post -World War ll, Trinidad and Tobago. Or for many, it’s the thrill of the masquerade (mas) bands, which spent months making themed costumes that show off all forms of visual artistry. Carnival, first recorded in the 13th century was originally a Catholic festival, celebrated before Lent in the Christian calendar. However, masquerades, predate the Christian festival, and has its origins in Fulani traditions, said to date back to 6,000 BCE.

The Fulani, Afrika’s largest ethnic group, are spread over many countries, but predominately in West Afrika. In 1910, more than 15,000 cave drawing were found in Algeria, depicting scenes from the social life of the Fulani. Some depict people wearing masks, and in one drawing, there is a running woman with a pair of cow horns on her head.

By the time of the Pharaonic dynasties, masquerades were fully established within their festivals. The use of masks was firmly rooted in their religious ceremonies, and with deities such as Hathor, a cow headed woman, who symbolised motherhood and fertility.

Masquerades have always been part of the cultural traditions of Afrikan societies, including that of the ancient Egyptians. But what are masquerades and what were their purposes?

The Spread of Masquerades to the New World

In the late 15th century, European quest for Afrikan gold and other trading commodities soon resulted in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. During the Maafa, or Afrikan holocaust, a conservative estimate claims that over 15,000,000 Afrikans were kidnapped, enslaved and taken to the “New World” from all over West Afrika. British involvement in the slave trade began with John Hawkins in 1562, and by 1636, the island of Barbados had become the first and most successful of England’s slave societies.The Peopling of Barbados

Most of the 231,000 enslaved Africans arriving in Barbados were taken from Nigeria (62,000) Ghana (59,000) Benin (45,000) Central Afrika (29,000) Senegambia (14,000) 9,000 from Sierra Leone and from Liberia, down to Cote d’ Ivoire (13,000).However, Afrikans were not the first to arrive in Barbados. In 1627, two years after the British first landed, eighty settlers, and 10 enslaved Afrikans landed there.

Beginning in 1642, male and female convicts from England were sent to Barbados to work as indentured labour. Soon afterwards, people began to be trafficked by organised gangs who kidnapped and sold them to ships bound for the Caribbean. Names such as “spirited away” or “barbadosed” were terms for such trafficking.

During the British Civil Wars (1642- 1651) over 50,000 Irish people were shipped to Barbados under the orders of Oliver Cromwell. And in 1687, after the Monmouth rebellion, 720 people from the west country of England were also transported there.

Crop-Over

The Crop Over grew out of the traditions of the people from the West Country and the Irish. It was instituted by the plantocracy and celebrated by bound and contracted workers at the end of the sugar-cane harvest. Initially, called ”Harvest Home”, this festival began in 1687. Fifty years after Afrikans were first enslaved in Barbados. The early Crop Over was led by a woman dressed in white with an elaborate white head-tie, decorated with a brightly coloured flower. She led the procession into the mill-yard, followed by carts of sugar cane, also decorated with flowers. The last cart carried “Mr. Harding”, a scarecrow like effigy, stuffed with the sinewy remains of the cane after the juice had been extracted.Masquerade Characters

Later, other characters were added to the Bajan Crop Over festival.These are: Mother Sally, the donkey man, the shaggy bear, the Green monkey, stilt walkers, and the Tuk band.

The Guyanese characters are: Mother Sally, Bum-Bum Sally, the Butting/ Mad Cow, Stilt walkers and the Flouncers. Both the Bajan and Guyanese masquerades have stilts walkers. However, in Guyana, Mother Sally and Bum-Bum Sally are two different characters. But in Barbados, both names are interchangeable for the same character. In Guyana the band, is simply known as the masquerade band.

Characters in Bajan Masquerade

The Tuk Band in Barbados would have appeared as part of the procession, only after emancipation in 1838. To curb slave uprisings, in 1675 a law was passed to ban the use of drums, making it a punishable offence. Later, in 1688 another law was implemented that saw the burning of drums and loud instruments. However, some enslaved people hid their drums and played music at night. As a result, there is some retention today, in the rhythms that were played in original masquerades.The Shaggy Bear character is an established part of Bajan masquerades. While some writers have placed a literal bear within a West Afrikan, context, that concept needs to be re-examined. The only bears in Afrika are the Atlas bears, who were introduced to North Afrika during the Roman Empire. However, the Atlas mountain range acted as a barrier, and there are no records of bears inhabiting West Afrika.

From a European’s cultural reference point, the Shaggy bear character appeared to be a bear, however, what was assumed, was not what it was. Enslaved Afrikans were not permitted to take part in those early Crop Over celebrations but had their own and so created masks that preserved their deities. And in true masking tradition, the Shaggy Bear, started off as something different.

The Green Monkey was not native to Barbados. It was introduced there from Senegambia, in 1670, shortly after enslaved Afrikans. As they bred, the sight of these wild animals would have reminded the enslaved of their homelands. It would have been natural to include to the Green Monkey in the masquerade as a reminder that both had been displaced.

Donkey CharacterAlthough donkeys were first domesticated in Afrika, there are no records that they had any role in the Afrikan belief system. Nonetheless, a more feasible explanation for the donkey character comes from the mummers’ tradition. A mummers’ or mumming play had its origins in European harvests festivals honouring the agricultural year. Mummers’ were processions of masked men who during winter festivals paraded the streets and who entered houses to dance or play disc in silence. When plays were later added to this celebration, one of the characters was a man dressed up as a horse. So this could have been the origin of the character.

After slavery was abolished, many former enslaved people left their island homes in search of better working and living opportunities. Guyana, located on the north eastern coast of South America was then considered “The food basket of the Caribbean” and people from all over the Caribbean flocked there. The 1892 Guyana immigration records stated that of the 40,656 people that immigrated to Guyana from the different Caribbean islands, the majority had emigrated from Barbados.

When people migrate, they take their cultural references with them and it is likely that the Guyanese masquerades evolved from the Barbados Crop Over festival when aspects of the festival, as it had by then evolved, were taken to Guyana by Bajans in the late 19th century.

Eye Witness Accounts of Guyanese Masquerade

“It’s like a parade, men on stilts. Men and women stuffed their bellies, hips and back with pillows to have big bellies, big hips and big butts. What it is represented is not what was. [The instruments were] Bongo drums. Flute, Shak-Shak The music they play is folk music new and old. They dance and gyrate their bodies, they wear colourful costumes. They would go through many different neighbourhoods, mainly Saturday and/ or Sunday afternoon. And when they perform, families would look out their windows, come out in their yard and watch from their fences, or come out on their bridges to watch. Some folks even get to dancing to the music too. Oh and you would give them a little change [money] for their music and performance.....not to mention if the[y] really perform...oh, and if you give them a good bit of change [money] they would really perform and extra too...they would shut down a corner for a good 15 to 30 minutes if many folks come out, give them money and dancing too...oh la la!”J.J. Georgetown, Guyana. c. 1970.

“I would go to the Masquerade, but I was afraid of the band. They put on some clothes and danced to the sound of the music. There were about four or five, somebody to collect the money, and they danced around it and picked it up. Children would follow the band. There was a stilt walker and Mother Sally, I always saw them when I was little, around 1948. [It was] Only at Christmas time.”

Gloria aged 87. c. 194 8, Georgetown, Guyana.

“They went up and down the street. They started before Christmas and went on for a week After Christmas, five weeks….flute, drums, bongo drums, small tassa drums, bass drum. Four musicians, dancers. It was different bands [that played] there were barrel dancers, people who danced on top of barrels, Mother Sally and the stilt walkers. When I went back to Guyana, four or five years ago, there weren't many and the costumes were not as good as when I was a child. [When I was young] if you go out shopping, they would be out and about collecting money.”

Jean aged 80s

“They play and they get money. They are on the public road dancing and they would stop traffic and try to get money from the vehicles. And they used to stop in front of the rum shop; a lot of drunk men came out and gave money.

The instrument was the kettle drums, African drums. There is a bull cow made out of bamboo, then they cover it with a horn. They move from left to right. They have a string attached to their shoulder and the person stand in the middle of the cow dancing.

The dancers move from left right, front to back, then they go on their right foot with their hips and hands moving, then you step on the back and repeat. The dancers would spin their foot inwards, heel and toe, that is the flounce. Sometimes there would be 10 to 15 dancing on the streets. They wore female clothes; they wore strip pieces of cloth made into a skirt.

Mother Sally was [a man dancing] on a stilt. Years ago, the character was made from bamboo. He was on a stilt and his head protruded from the character. I was scared. The frame was made from bamboo or raffia. Bum-Bum Sally wore a big bum.

Christmas time, they just go round but not every band had the characters. When I was small, in the early days, women didn't dance, it was just men.”

Westley. West Coast Berbice, Seafield village

“The music was shrill played on a flute. There was drums. There were flouncers doing a kind of heel and toe dance. I was between four and six years, when I saw my first masquerade. I was not aware of Bum- Bum Sally; my grandmother would not have pointed that out to me. That was not something for children.”

SM Georgetown. c.1962

“There is the Bum-Bum Sally dance, it is vigorous. It is a man dancing; it is not a graceful movement, a gyration. It is a very sexual dance, but from a man's perspective, bold! The stepping is a man’s exaggerated sexual movements. The man is accentuating the behind. They would drop to the ground. They spread their legs and drop to the ground with the bum just showing in the air. It is a wild dance.”

C.W. mid -sixties

Most West Afrikan cultures viewed curvaceous women as symbols of affluence, good health and prosperity. Today, in the Efik culture of Nigeria, it is customary for teenage girls to be fattened up in preparation for marriage. During that time, older women instructed the younger ones in sexual life, etiquette, and femininity. Could that have been the origin of the Bum-Bum Sally character? Possibly, but it is more likely that the character evolved from the mummers tradition that was transported to the Caribbean.

In the 16th century it was customary for men to dress as women in British theatre. In 1642, Oliver Cromwell, banned theatre plays because they were considered places for sexual amusement, where serious matters were treated frivolously. In mummer plays, cross dressing was a common and acceptable practice. And while some scholars claim that the character is a fertility symbol, I think that Bum-Bum Sally was handed down through the mummers’ tradition and later adopted into the Bajan masquerade.

However, when it was adopted into the masquerade, it was a means of creating the desired aesthetics of the Afrikan woman. Nonetheless, over time, the character morphed into what we see today, a character of hyper-sexuality and mirth.

Stilt Walkers

Stilt walking is firmly established in the Afrikan psyche. It was one of the cultural practices carried to the Caribbean by enslaved people. In some Caribbean islands, stilt walkers were given the name Moko Jumbie. The name “Moko” means healer in Central Afrika, while jumbie, in the Caribbean is a generic name for a ghost, or evil spirit. But depending on whom you ask, Moko, means different things. To some, stilt walkers became the spirit of fate and retribution.

In West Afrika, the understanding is different. In some cultures Moko is a god, while in other cultures, stilt walkers are believed to be the protective guardians of their villages. They believed that because of the stilt walkers’ height, it was able to reach and drive evil spirits away by mocking them with supernatural powers. Stilt walkers, were also viewed as an important aspect of religious worship.

Butting Cow/Mad Cow

It is not known when the cow was added to the masquerade. However, in 1838 an influx of people from India arrived in Guyana as indentured labour. Because of their religious reverence to the cow, it may have been added to the masquerade along with the Tassa drums that also came from India.

Rhymes

Both masquerade and mummers’ performers have traditions of making up rhymes as they went along. Here are two popular rhymes from Guyanese masquerades:

1. “Drink a rum on a Christmas morning

Drink a rum on a Christmas evening

Mama drink if you drinking.”

2. “Christmas comes but once a year And every man must have his share But poor brother Willie in the jail Drinking sour ginger beer Now pick up the band and awe go.”

Flouncers

Dance in masquerade became a specific part of Guyanese culture. Flouncers were the name given to the dancers and flouncing was the type of dancing they performed. The flouncers would spin and twist and do acrobatics and when they spun around, their dresses spun around too. They were very nimble on their feet as they picked up money that onlookers threw, that part was a graceful dance.

Different Afrikan cultures had their own traditional dances. Dances were used for emotional expression, as parts of annual festivals, rites of passage, recreation and for telling stories.

Music

To the Afrikan psyche, music was always active and communal. Music was used as a means of communication, and also communion between mortals and the spirit realm. Where there were no instruments, hands and feet were used to keep rhythm. Therefore, dance and music was always intertwined and had a purpose.Musical Instruments

This account of Afrikan drums is given by Dutch slave trader, Willem Bosman. It was published in the early 18th century."Their second sort of instruments are their Drums: of which there are about ten several sorts, but most of them are excavated Trees covered at one end with a Sheep-skin, and left on the Ground like a Kettle Drum, and when they remove it they hang it by a string about their Necks: They beat on these Drums with two long Sticks made Hammer Fashion, and sometimes with a straight Stick or with their bare Hands; all which ways they produce a dismal and horrid Noise: The Drums being generally in consort with the blowing of the Horns; which afford the most charming Asses Misick that can be imagined to help out this they always set a little Boy to strike upon a hollow piece of Iron with a piece of Wood; which alone makes a Noise more detestable than the Drums and Horns together. Of late they have invented a sort of small Drums, covered on both sides with a Skin and extended to the shape of an Hour-Glass."

A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea. Willem Bosman. Printed in 1705.

Dundun Talking Drum -Horniman Museum Collection

Bosman in his description of Guinea, talks of this type of drum as a new invention. The eyewitness to the Urhobo Masquerade, nearly three hundred years later, describes the same instrument along with hook like drumming stick. The Dundun talking drum is often played at celebrations such as weddings, held by members of the Yorùbá diaspora community from Nigeria living in London. It is known as a talking drum, as it is used to imitate the Yorùbá language, which is tonal, where words have different meanings depending on the pitches at which they are spoken. The drum is held under the left arm, and by pressing on the thong lacing, the drummer can vary the tension of the drumhead to create different pitches. The patterns of speech rhythms are beaten out with the curved stick.

MUSEUM NUMBER: MT40-1995

LOCATION: On display: Horniman Museum > Music Gallery > Side D - Listening to Order > Case D2 - Classification > position 125

PLACE: Africa; West Africa; Nigeria

The three types of bells used in Afrika, are: the Pellet- bell, the Clapper-bell and the Struck-bell. The Pellet- bell has a free moving object in the cavity and is closed. The Clapper-bell has an attachment on the inside, while the Struck- bell is struck with an implement. Bosman’s description of “a hollow piece of iron that is struck with a piece of wood” is none other than a Struck bell, which are used in some masquerades.

MUSEUM NUMBER: 28.76

PLACE: Africa; West Africa; Nigeria; Benin City

Clapper Bell

MUSEUM NUMBER: 1970.28

PLACE: Africa, Central Africa, Democratic Republic of the Congo, East Kasi, Lukolela.

Instruments in Guyanese Masquerade

The main instruments used in Guyanese masquerades are classed as idiophones and membraphones. This is coupled with the flute which is an aerophone.Today, musicians mainly play the Djembe drums, the Shak-Shak, the Triangle and the flute. However, it depends on whether you live in the capital or country areas and what instruments are readily available.

Afrikan drums are very diverse, and over time, different type of drums were played during the masquerades. The Djembe drum is shaped like a goblet and originated with the Mande people, about 800 years ago. It is about 25 inches high and made from a single piece of wood. The top is covered in animal skin with ropes securing it, to keep it taut. The drum was later adopted throughout Guinea, as West Afrika was then called.

It is believed that the drums possess three spirits: the spirit of the tree, the animal whose skin it was, and the maker of the drum. Originally, Djembe drums were used exclusively by the griots within the Mande culture. Griots were trained historians responsible for passing down oral histories and genealogies. They were also singers, poets and social commentators.

MUSEUM NUMBER: HC.2014.38

Afrikan drums are very diverse and over time, different types of drums were played during the masquerades. The kettle drums could be either small or large. Afrikan Kettle drums were made of copper or clay and came in pairs. The main beat was played by the right hand and the left hand played the secondary beat. Smaller drums were designed to be cupped under the left arm when played. Bongo and Tassa drums were also small drums which made them easier to transport.

Drums had a meaningful presence even when they were not being played. And drums had deep symbolic meaning to the Afrikan, for example, the drum was the female and the stick the male. Also drums were used to signify the spirit world; therefore the drum was a mask for evoking spirits.

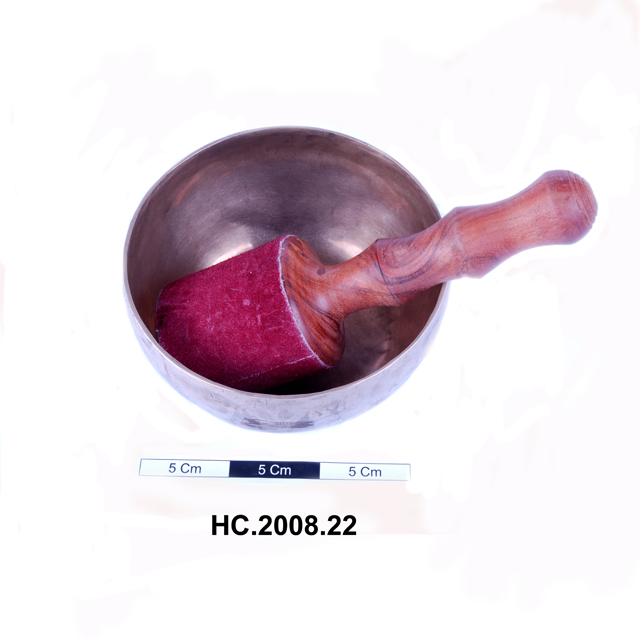

Kettle Drums similar to this one, were used in the Guyanese masquerade.

The shell is a wide and domed section of a calabash. Goat-skin membranes at both endswith remnants of hair on outer surfaces. The hair has been scraped away from the centre of the head. The lower membrane is an irregular shape. The head is tensioned with goatskin straps, which are threaded between the membranes around the sides. With partially legible label.

MUSEUM NUMBER: M19.4.66/8

LOCATION: On display: Horniman Museum > Music Gallery > Side D - Listening to Order > Case D2 - Classification > position 112

The Tassa drum came from India. It was bought to Guyana by indentured labourers who were contracted to work in Guyana after slavery was abolished.

The Shak-Shak is a rattle made from the bottle gourd tree. It is also native to Afrika. Pebbles or seeds are placed in the egg or oval shaped gourd, then shaken, hence its onomatopoeic name. Maracas and Shak-Shak’s are the same instruments. They are similar to the West Afrikan Shekere.

Burnished gourd rattle.

MUSEUM NUMBER: HC.2010.43

MUSEUM NUMBER: HC.2012.17

The Triangle, is a metal object instrument, shaped like a triangle, but is curved at the edges. It has an opening at one side so that it can vibrate; it is struck with a straight metal rod. This instrument has been in Europe since the 10th century, and was played in religious music. Related to the Sistrum, an ancient Egyptian percussion instrument, it was also played during religious ceremonies and when coming into the presence a deity. Many Sistrum’s were decorated with images of Hathor, who was also the goddess of music and dance.

MUSEUM NUMBER: M24.8.56/123

DATE: 1868

PLACE: Africa; Horn of Africa; Ethiopia

Flutes

The Flute was one of the earliest musical instruments of civilization. Flutes were originally made from bamboo, wood, or reed with the mouthpiece either at the side or at the top. The flute had a number of holes that were either covered or opened with the fingers, to get the pitch. These are three examples of flutes found throughout West Afrika.Notched end-blown flutes

Notched end-blown flutes. Each is a single piece of wood with a round central bore burnt out. These are open at the top and constrict to a narrow opening at the bottom. The heads are each carved to a wedge shape and then a U-shaped notch carved into the centre. Two raised sections at the side of each flute have finger holes finger holes positioned at their centre. Below the heads the necks are constricted and each is tied with a tartan ribbon. The bodies from here down are covered in snake or lizard skin, which is stitched into place along rough seams at the back. The shorter of the two pipes has museum number M14.3.61/5. It has a bulbous section at the distal end that is not covered with skin.

Notched flute

MUSEUM NUMBER: M15.6.55/25

Notched flute. A bamboo tube open at both ends, the central section covered with brown leather, which is stitched in place along an irregular seam at the back. The upper rim has a rectangular notch cut into the front edge. Immediately below this is another leather band, which is slightly darker in colour and has a strap attached. Four large widely spaced finger holes, two of which are positioned on the leather covered section and the other two beneath. The distal end is choked by an inserted disc of gourd with a smaller circle cut in the middle. A dogtooth design is cut into the wood on the front of the instrument in the small gap between the two leather strips.

Oja Whistle

MUSEUM NUMBER: M15.6.55/33

Oja, whistle, notched flute, carved from a single piece of wood that is closed at the distal end. The proximal end is cut with a wide, rounded notch on the front and back rims. A ridge encircles the body about one third of the way down with a small, round finger hole on the side to the player's left. The rectangular distal end has a hole for a carrying cord at the bottom corner to the player's right. Two diagonal crosses are carved into the front of the instrument, one on the head and one at the distal end.

Afrikan Masquerade

"There is flute music a little bamboo thing that they would play. And drumming and they paraded around the village, and as they walked through the village, they dance to the music that was being played by them. The ones that stuck out for me were the characters in grass skirts. They all wore different masks, depending on the character. Each character, I was told meant something. They symbolised something to do with spirits. They were all men in the masquerade, there was one on stilts. Because it was just for the village, it was quite small. It was very colourful and noisy. There was lots of tinny sounds as opposed to a drum based sound; they [The drums] were small and they played it under their arms. And they played with a hook-line stick. People made up their own instruments and there were cow bell sounds. It reminded me of the rolling calf from Jamaica, which was something to be feared. They tried to frighten you; the masks were scary and they would come towards you to get a reaction from you. The music which was noisy made you want to investigate. It was during the Christmas season. It is a celebration of what the earth has given us."Eye witness account of the Urhobo Masquerade. Abraka, Delta State, Nigeria.

c. 1979.

Conclusion

Afrikan’s had for thousands of years been practising life affirming rituals and masked ceremonies. Although displaced, their thought processes and cultural references remained intact, despite their movements and languages being severely restricted.In Barbados, masquerade as we know it today, became a fusion of Afrikan and European culture. That fusion came about because Oliver Cromwell had banished so many English and Irish to Barbados. That resulted in the mummers’ tradition becoming the first cultural festival to be re-enacted in Barbados.

The tradition of Mumming, a celebration of fertility, birth and renewal, was practised in Europe for centuries before being exported to Barbados in the early 1600’s. The tradition of wearing white attire came from the mummers’ Christmas festival, when a white decorated costume was worn with a bishop’s mitre, or crown. This was reflected in the costume worn by the leading character in the Crop Over procession. Many, of those taking part, and those watching had no idea what they were witnessing was a masked religious ritual.

Enslaved Afrikan’s had their own masking traditions that they took to the Barbados and which they adhered to in secret. And because the enslaved were not a homogeneous mass, different variations of masking traditions were retained and eventually mixed with European influences. There is no evidence to suggest that Afrikan’s took part in these early celebrations, however, they may have been silent onlookers. Those traditions formed a cultural fusion that branched off into a different kind of masquerade, once in Guyana.

The mummers’ festival was foremost a street performance that incorporated a play. Both performances took part around Christmas time and saw masked performers dancing on the street. Early mummers’ tradition saw mummers’ visiting stranger’s homes. Where as in Guyana, the masquerades stood in the yard, or performed outside rum shops for money.

Mummers also had a history of making up rhymes. This can be traced back to ancient Greece, where the Greek god Momus, apart from being a cross-dressing deity, was also the god of satire, mockery and poetry. These components, also found in the Guyanese masquerade, has its origins in the Kaiso musical tradition that has its origins in West Afrika.

Although many of the components making up masquerade and carnival are credited to Ancient Greece, deeper research goes back to the practices of Ancient Egypt. Those Ancient Egyptian influences were absorbed by Greeks and later incorporated into Catholicism when the Romans wanted people to turn to Christianity, the concession being, that they kept their former practices, under the new guise of Christianity. Incidentally, in many of the older mumming plays, one of the characters was either an Egyptian, Moorish king, or a black knight. And in Cornwall, Mummers’ day was known as Darkie Day, perhaps a long forgotten reference to its origins?

Ancient Egyptians venerated the cow in their religious practices, as did many ancient religions, where the horns of the animal were seen as a symbol of power and sovereignty. The Fulani, had an even longer history of such reverence; their supreme deity being the cow god, Geno. That the cow should have a place in masquerade should not be surprising. When Indentured workers, arrived from the Indian-subcontinent, they brought with them their religious and cultural ideas. Today, many popular world religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism, in one way or another, venerate the cow. So it is no surprise that we find this object of veneration reintroduced into the masquerade.

Today, masquerades in Guyana does not have the importance it had years ago. Traditional Christmas celebrations have been replaced with many new practices, brought in by ex-pat’s holidaying from the USA. Also the influence of television, in promoting American culture, has also swayed people to making a cultural shift. For car drivers using the public roadways at Christmas-time, masquerade has become a nuisance. The antics of the mad cow, often jumping out in front of cars is more of an annoyance than a cause to celebrate. Nonetheless, masquerades seem to be more popular in the country areas than in the city, perhaps because there are not the many distractions associated with city life.

Today, a Guyanese masquerade bears no resemblance to what it once was in Afrika. Now, it is more like a walking pantomime, because both the performers and the audiences have lost the meaning and understanding of what was being conveyed through the mask. Masquerades no longer, define social roles or communicate religious meanings in a way to be clearly understood. Although many of the original practices were centred on the worship of deities, such understanding is lost and many would say is no longer significant.

The only masquerade characters that have a direct link to the Afrikan belief system are the stilt walkers and the shaggy bear. There is some also retention in the type of music and the musical instruments. Those early European onlookers, who interpreted the bear like character as such, did not know what they were witnessing. To those early enslaved Afrikan’s, that figure was believed to be the spirit incarnate, as masquerades are not seen to be normal human beings.

Igbo stilt walker masquerades are known as Izaga, or Ulaga masquerade. The Ulaga masquerade is only seen occasionally; during the funerals of prominent men, or in recognition of someone’s importance within the community. The Ugala always wear black while Izaga wears white and rings a bell to announce its presence. Izaga is taller that Ulaga and both are there as a mark of respect to bid farewell to the deceased. The Yoruba, the second most populous group to be enslaved in the New World, also had masquerades that had stilt walkers. Their Egungun festival involved the return of the spirits to the ancestors. The literal translation of the name egungun means “walking dead”. Dance.

Some dances were connected to the worship of gods, as in the case of fertility dances. Such movements were designed to stimulate the passions of both participants and onlookers. That being the case, the Bum-Bum Sally dance, could be classed as a fertility rite.

That carnival and masquerade should be lumped together is no coincidence because Catholicism and masking traditions had already been syncretized thousands of years ago. Masking traditions were dominant in ancient Egyptian festivals. So carnival in its essence is a masked celebration of masquerade, which evolved from Ancient Egyptian festivals.

References

* https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=MR1svTwGws8 * http:pointblanknews.com/pbn/exclusive/special-report-who-are-the-fulani-people-and-their-origins/ * https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=ltXfR_TIlEE * https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=MR1svTwGws8 * http:pointblanknews.com/pbn/exclusive/special-report-who-are-the-fulani-people-and-their-origins/ * https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=ltXfR_TIlEE * https:en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afro-Barbadians * https:core.ac.uk/reader/215278048 * https:www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/irish-roots-were-there-irish-slaves-in-barbados-1.2337597 * https:www.nytimes.com/1973/02/25/archives/poor-backward-and-adamantly-white-in-a-black-world-culture-doomed.html * https:irishamerica.com/2015/10/the-irish-of-barbados-photos/ * https:bridgwater-tc.gov.uk/history/bridgwater-slavery/somerset-rebels-sold-into-slavery/ * http:nsadulsausa.over-blog.com/2020-04/the-white-slaves-of-england-compiled-from-official-documents.-with-twelve-spirited-illustrations.html * https:panamericanworld.com/en/magazine/travel-and-culture/barbados-cultural-gem-what-is-tuk-band/ * https:folkplay.info/sites/default/files/papers/201111/Rowley2011.pdf * https:folkplay.info/sites/default/files/papers/201111/Rowley2011.pdf * https:barbados.org/monkeys.htm#.Xx077J5KjIU * https:www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-29742774 * https:www.vanguardngr.com/2011/03/fattening-tradition-in-south-eastern-nigeria/ * https:hekint.org/2017/01/29/a-tribes-fattening-culture-and-its-impact-on-health/ * https:www.enotes.com/homework-help/why-did-puritans-close-down-globe-all-together-61973 * https:www.mun.ca/ich/inventory/profiles/xmastrad/mummering.php * City of Sin, London and its vices, Catherine Arnold. 2010 * https:repeatingislands.com/2009/10/28/moko-jumbie-stilt-dancing-rooted-in-the-ancient-traditions-of-african-slaves/ * https:strangersguide.com/articles/stilt-walkers/ * https:repeatingislands.com/2009/10/28/moko-jumbie-stilt-dancing-rooted-in-the-ancient-traditions-of-african-slaves/ * http:www.unitycommunity.com/stiltwalkers.htm * https:stthomassource.com/content/2019/03/01/the-evolution-of-the-mocko-jumbie-in-the-v-i/ * https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPnsJtycxmM * https:www.drumconnection.com/africa-connections/history-of-the-djembe/ * Traditional African and Oriental Music Otto Karolyi 1998 * https:www2.palomar.edu/users/warmstrong/ww0503.htm#calabash * https:www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/performing-arts/music-theory-forms-and-instruments/maracas * https:www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/553814 * http:www.instrumentsoftheworld.com/instrument/176-Triangle.html * https:www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/African_dance * https:en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Momus * http:quakercitystringband.com/a-history-of-mumming-how-the-mummers-got-here/ * https:addameer.org/journal/archive.php?id=momus-greek-god-669280 * https:www.youtube.com/watch?v=ltXfR_TIlEE * https:www.stabroeknews.com/2017/12/31/sunday/arts-on-sunday/wanted-a-rescue-for-the-street-masquerade-bands/ * https:www.pulse.ng/lifestyle/food-travel/4-things-you-should-not-do-when-you-encounter-a-masquerade/f47lmky * https:geography.name/masks-and-masquerades/ * https:www.caribdirect.com/the-familial-relationship-between-guyanese-and-bajans-part-i/ * http:www5.csudh.edu/bdeluca/ThePowerofMasks/hum310/2_Africa.html * www.encyclopedia.com/religion/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/fertility-and-vegetation-cults * https:www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2018/12/25/where-are-the-true-masquerade-bands/ * https:www.thingsguyana.com/everything-you-need-to-know-about-nenwah/ * https:wonderfulcollection.wordpress.com/2014/11/11/shak-shak/ * https:en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cucurbitaceae * http:www5.csudh.edu/bdeluca/ThePowerofMasks/hum310/2_Africa.htmlttps:en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1898_Windward_Islands_hurricane#:~:text=The%20Windward%20Islands%20Hurricane%20was,Vincent%20was%20catastrophic * https:www.caribdirect.com/the-familial-relationship-between-guyanese-and-bajans-part-i/ * http:www5.csudh.edu/bdeluca/ThePowerofMasks/hum310/2_Africa.html * http:www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/gods_gallery_07.shtml * https:hubpages.com/holidays/The-Magnificent-African-Masquerade * https:www.legit.ng/1126026-igbo-musical-instruments-names.htmlI do not own the copy rites to the photographs of the musical instruments, which belong to the Horniman Museum.

Many thanks to Val and Obiora.