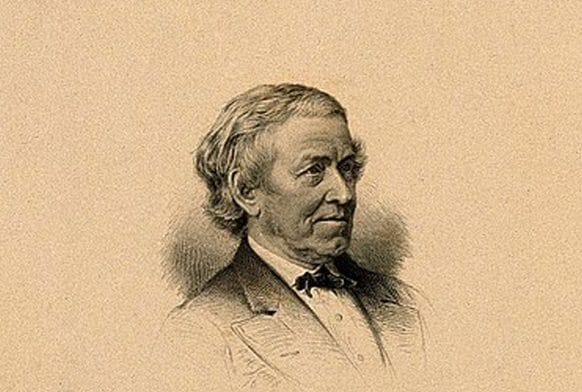

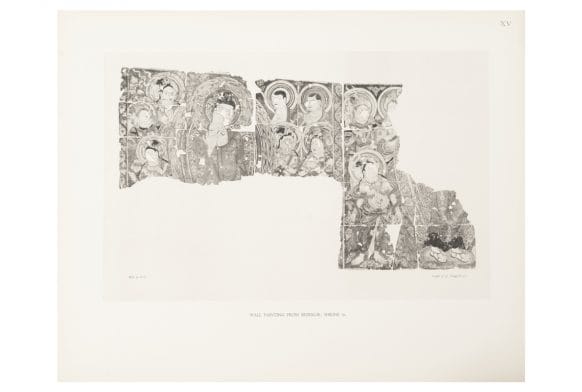

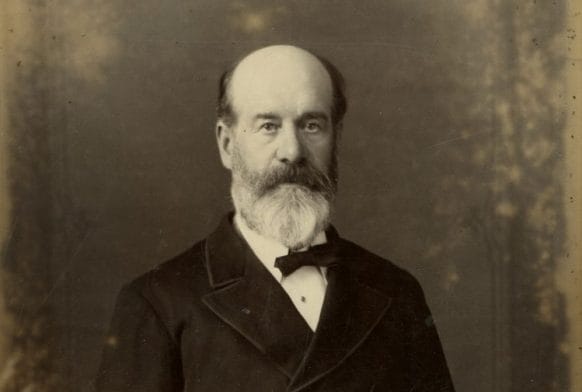

Miniature portrait of Maharaja Kharak Singh (1801-1840). Gouache (possibly heightened with gold) on ivory.

Kharak Singh succeeded his father as to the throne of Lahore in 1839. Compared to his father, he was regarded as weak in character and incompetent as a ruler. Under the influence of Chet Singh, a court favourite, his father’s prime minister Raja Dhian Singh was ignored and insulted. A plan to assassinate Dhian Singh was uncovered so the minister formed a coalition with Prince Nau Nihal Singh, Maharaja Kharak Singh’s only son (who was much more like his grandfather, being in possession of a fiery and ambitious temper) and with some Sikh chiefs to do away with Kharak Singh. To this end, they circulated a rumour that he contemplated submission to the British Government, when the Khalsa Army would be disbanded. This appealed powerfully to the soldiery, who consequently looked upon the maharaja as a traitor to his country. Soon after, Dhian Singh with his cohorts forced their way into Maharaja Kharak Singh’s private apartments and killed his favourite, Chet Singh. Kharak Singh was deposed after ruling for just three months, and his son, Prince Nau Nihal Singh, placed on the throne. The deposed maharaja died the following year, not without suspicion of poisoning, and his son mysteriously met his death by an apparent accident while returning from his father’s obsequies. Suspicion fell largely on the prime minister, Dhian Singh, and his allies. The painting can be dated to around 1850-60 and was probably completed either at Lahore or Delhi. Dignitaries, local rulers and colourful characters were standard subjects for ‘Company paintings’ in the Punjab. Their principal customers were Europeans living and working in the India subcontinent.