Hi, can you tell us a bit about yourself and your process?

I like to call myself a ‘Creative Practitioner’ as I merge a few disciplines into my arts-based practice, all revolving around creativity and community.

I’m really committed to working with people and am especially interested in individuals and groups who often don’t have a voice in the mainstream or whose voice is misrepresented.

The things that really inspire me are how our lives are driven by these hidden mythologies that we enact, often without even knowing it. When I work with people I’m often trying to uncover these social narratives that help us explain who we are as people inhabiting this planet. This usually manifests itself through projects that are installations, performances, guided walks (either live or recorded) and text-based works.

I love language and how we are able to portray our lived experiences through both poetic and verbatim collections of words. I also spend a huge amount of time organising and dreaming up new ways of connecting artists who are dedicated to working with community, and are dedicated to social justice and change.

I really see this movement of social art as an antidote to these times of deep material culture that is sinking the planet in a rubbish heap.

Where did the idea come from for Scrolled Life Stories?

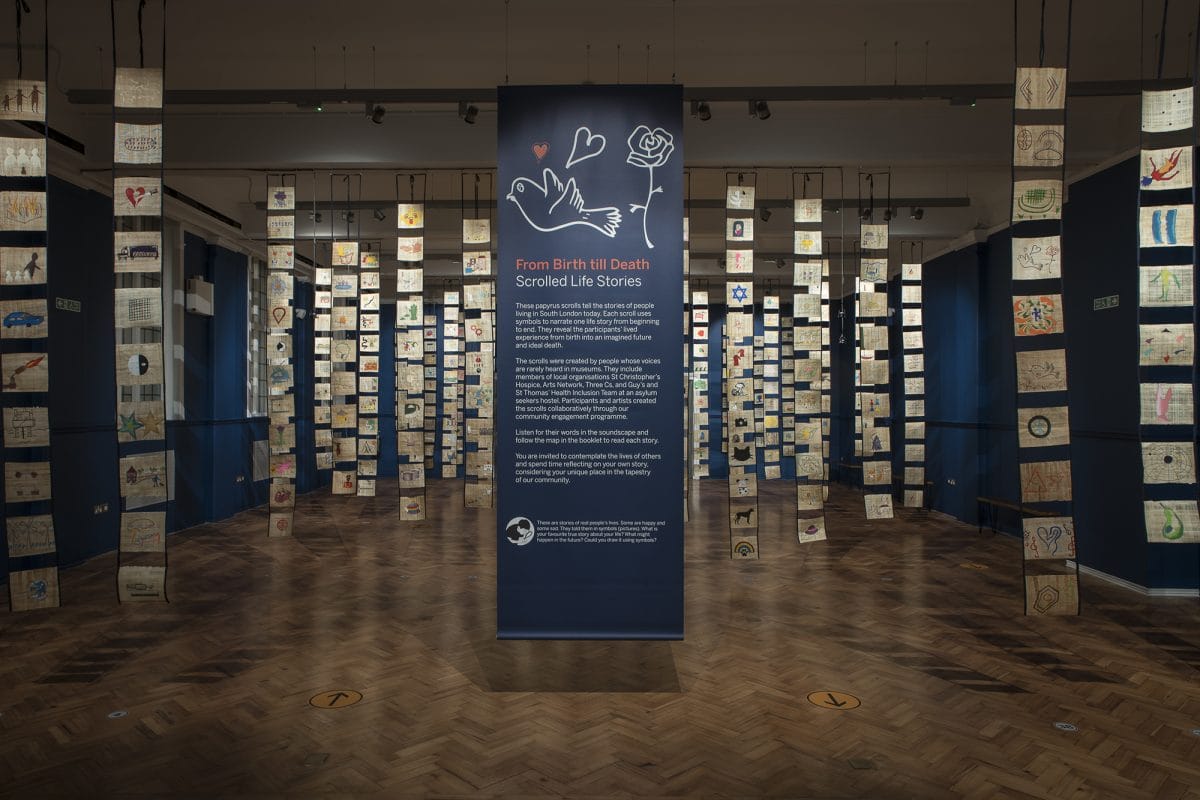

The Studio at the Horniman had been in place for a few years, and I was watching it very closely. There are very few, to almost no, museum spaces dedicated to showcasing work created directly with the community.

I have worked with the Horniman Community Team on a few smaller-scale projects before and was really impressed with their reach into the community, and service to various groups that tend to care for vulnerable and or excluded people. My overwhelming sense was that I wasn’t seeing these people in the Museum, and I longed to make their stories first and foremost.

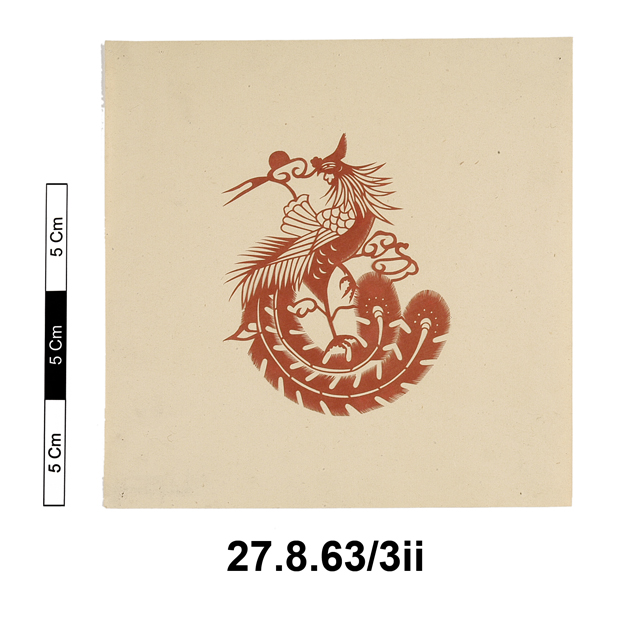

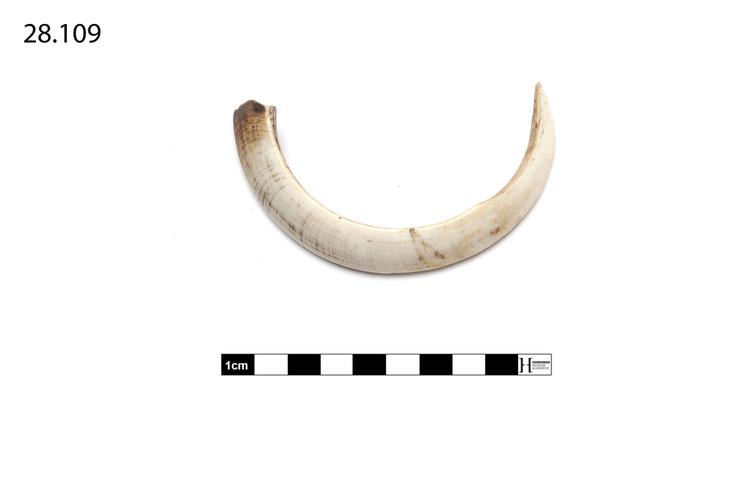

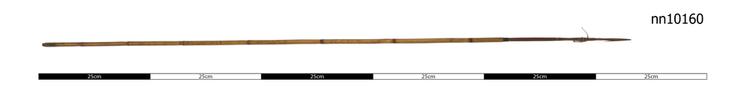

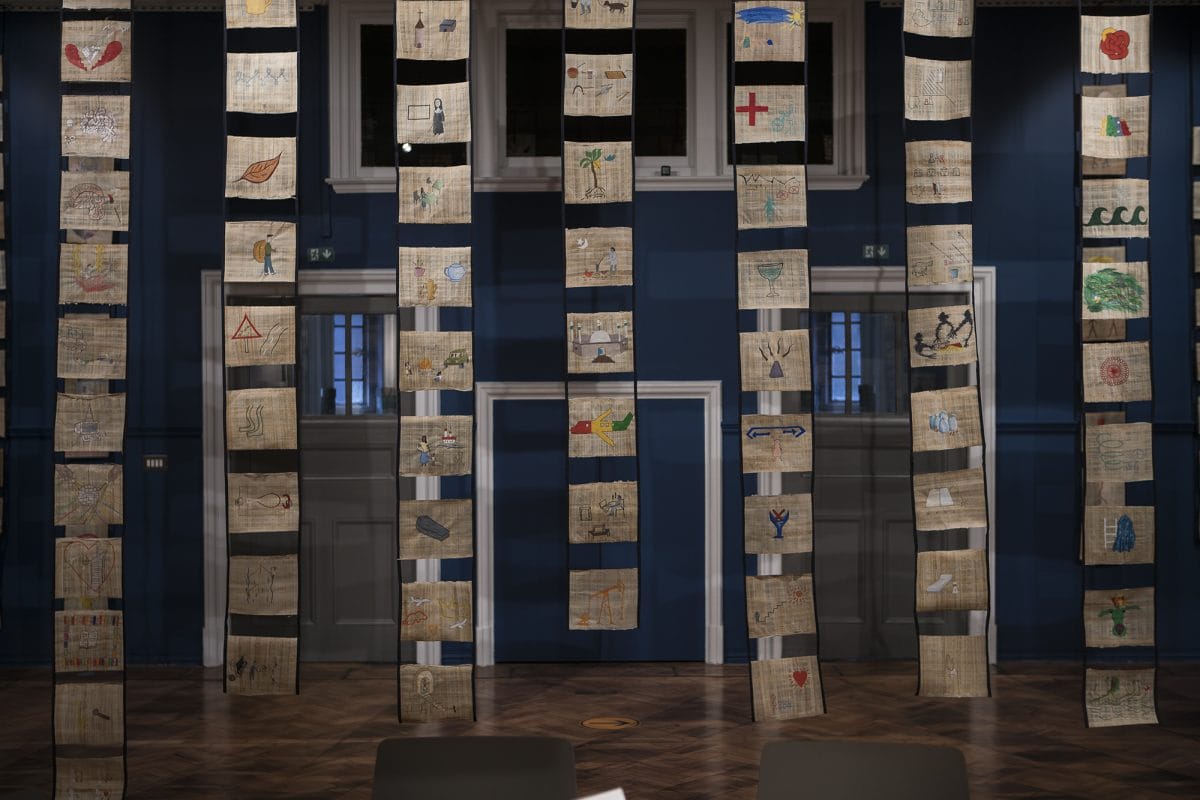

Scrolled Life was designed with two main things in mind: a mode to represent the lived experience of community members, and a visual that would fit seamlessly into the Museum’s collection. The exhibition is not directly in conversation with the collection but rather sits alongside it as a sibling in the family.

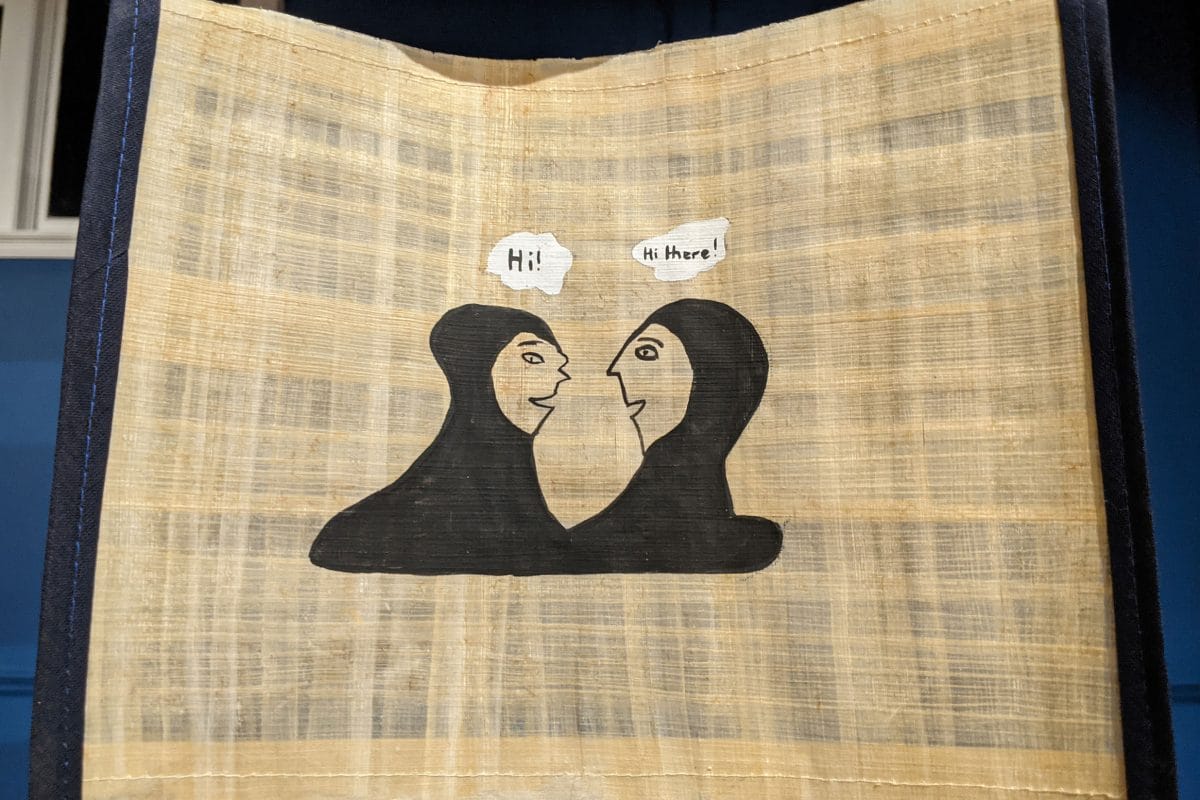

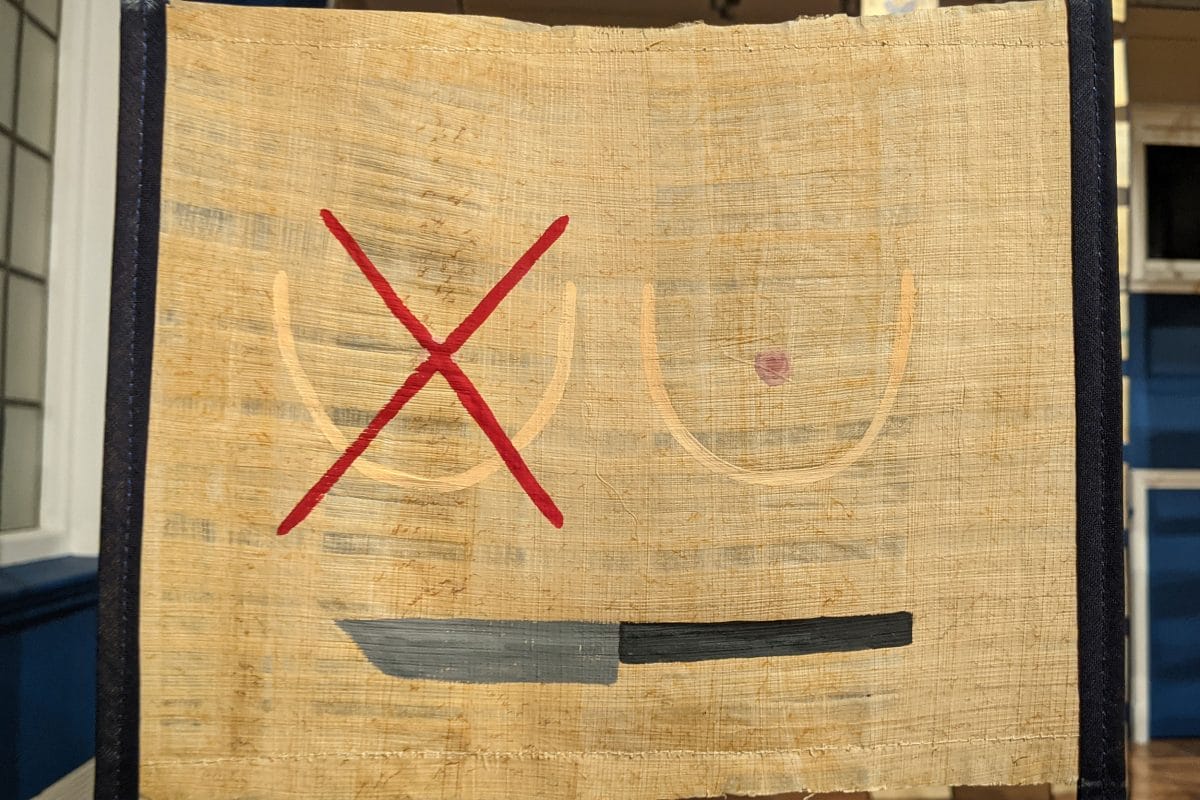

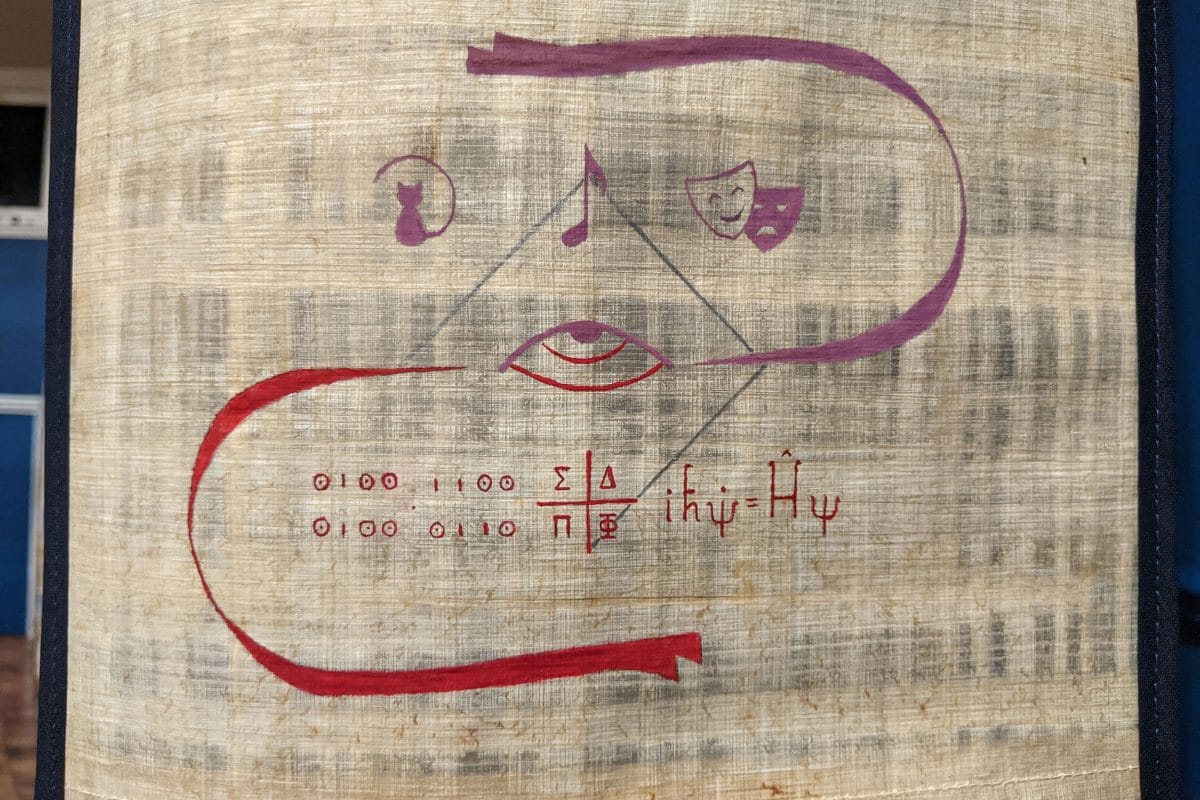

I was inspired by the earliest marks that we made as a species to tell our stories and mythologies: cave paintings, petroglyphs, hieroglyphs. Drawing activates the right side of the brain and allows us to tell stories through feelings rather than words, text or language. So the invitation comes from a visceral, emotive place.

The actual creation process of archiving the lived story through sequential narrative was informed by Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET). NET was developed in conflict zones to help cope with PTSD but now is used in general for people who may need help contextualising issues in their life. The process helps you tell a narrative story so that the highs and lows all fall within the larger narrative of who we are and help us not get stuck on the lows.

To bring this process into a simple art-making exercise is quite a powerful way to give individuals a chance to reflect upon their own life stories.

How was it working with all the community members to create this work?

Working with various community groups was really life changing. Each group and each individual was incredibly varied, and everyone had their own powerful lived experiences.

We worked with hospice patients and explored what making a life story was like at the end of life, when the imagined future and ideal end was so close.

We worked with a really creative and deep thinking group of individuals who have had personal experience with mental distress in the various forms that this may come. One in four adults in the UK will experience mental health issues, and this was such an important group to share their personal stories of resilience and recovery.

We also worked with asylum seekers living in a hostel and seeking a better life in the UK. A hugely varied group from all over the world, from a shepherd to an accountant. Their stories of perseverance and their incredible love for their host country, our London home and UK reality, was so inspiring and absolutely does not match what you see in the media.

As a child of migrants and as someone who also decided to make UK my home (in a much different way) I knew that these would be great neighbours, hardworking residents and dedicated citizens. For the asylum seekers, the imagined future was tantamount.

Working with each of these groups was so very different. So the way we approached the drawings was tailored to each group. We started first with a timeline sketch and then we slowly chose the top ones we would represent. Of course, we are more than just a dozen images, this project is not about our whole lives but think of it as a film trailer.

I will say that if you’re wondering why these scrolls don’t look like what you’d imagine the Old Testament was written on, you’re right! They are more like film strips, and when we think of ‘scrolling’ through our life we have moments that we land on, which become individual stories and segments that form our collection of self: our scrolled life.

Each of us are micro-museums with a collection of stories, memories, emotions, successes, failures and dreams. Here is an opportunity to consider that collection in others and in ourselves.

What would you like visitors to think about when they visit From Birth Till Death: Scrolled Life Stories?

There are two main invitations taking place in this exhibition.

The first is to understand that the Horniman, as a museum of cultural anthropology, tells us who we are as people on this earth, and that part of that story is who we are as residents of London.

There is a real joy in seeing artifacts from around the world, especially First Nations peoples, and we can learn so much about connecting to a deep sense of magic and animism. I want to remind audiences that we too are a curious bunch in this cosmopolitan city, with such an incredible diversity that is our strength.

The second invitation is for audiences to take a moment to reflect on their own lives as they spend time looking at the lives of others. So the exhibition space is designed around a central table and a simple yet poignant activity pack that allows you to design your own life scroll.

This is an invitation to take a moment, to reflect, to consider and to imagine a bird’s eye view on your journey through life.

We don’t often give ourselves such opportunities when we are too busy surviving and striving!

What mediums do you enjoy working in and why?

I have specialised in a combination of forms.

I tend to work site-responsively; this means that I take into consideration the physical site where the artwork may be happening and also the social context around it. Generally, I create installations and sometimes these can include performances. I love spoken word, song, creative movement, and folk.

My main medium is working with people, so you will find that central to my work tends to be others, not myself. I’m sure we could sit in a café and chat all day about our personal lives, but when I make work I am most interested in sharing and exploring the lives of others rather than my own. This is because I consider cultural production the best way we can know ourselves as a society, and the responsibility of the artist is to give that voice over to others, especially those who could really benefit from a platform.

Politics was always huge in my family. I’m a settled citizen in a country I wasn’t born in, and raised in another country by parents who settled and became citizens there but were born somewhere else. My family history is one full of migration and I did my DNA to explore that!

Politics remains a very central part of my life. When I say this I don’t mean political parties, but the origin of the word, polis or city or body of citizens. This deeply inspires me and my creative process. There is an endless amount of material when we consider the city as not just a place of concrete and steel but of memory and myths.

Why is this exhibition relevant today?

We had no idea when we were developing this over the last two years it would be opening after a series of lockdowns during a pandemic, social distancing and the collective trauma that goes with it.

This is compounded with the cultural awakening of the climate crises and our first-hand experience of how much cleaner our world can be when industry and traffic halts. The surge of the civil rights movements across the globe, including the Black Lives Matter movement, is all intensified in this period. Instead of masking the bigger issues at stake the health crisis has heightened them. Naming the problem is the first step towards addressing solutions and working together towards actions to create a new, more just world together.

What we can offer through this exhibition is a creative site of care, offered by the Horniman and the participation programme to members of the public through a simple yet effective act of engagement. When you visit, there is a booklet to take you through the exhibition and read the stories, and an activity to create your own scroll. I think we are all needing some time to reflect on what’s happening!

St Christopher’s Hospice Community Action Team is hosting a community takeover and there will be Horniman Volunteers on site. We are hoping this will become a real hub of healing. We need gentle and safe ways to congregate, to be together and make sense of these times and of our lives. I will be there each week after opening as well, to share stories and work facilitate the activity and listen to those who need to share.

What do you have coming up?

2021 is really rolling for me already! I am part of Social Art Network a mutual aid group for social practice artists across the UK. I also am working with Axis, an organisation dedicated to artist support.

Through these two organisations I am helping deliver two new exciting digital projects: Social Art Library, a new digital platform for archiving and collecting process around socially engaged art, and Social ARTery, a new online work, and a social media platform for artists and communities.

It’s not small effort to take on the tech giants and get off the data mining circuit, but it’s something that I am really dedicated to.

I am also working on a public art commission with Poet in The City and Greenwich Council for Woolwich City Centre, which I am delivering early in 2021.

Finally, I am touring a socially distanced drawing project inspired by this exhibition called WTF Just Happened?! It’s a way to sit and draw with people on how this time has affected changes in their lives and create a huge pool of drawings from across the country that will become an important archive of the times we are living in.