Tell us a bit about yourself

I am a French artist living in London. I studied fine art in France and later went on to follow a programme in Arts and Politics (SPEAP) at Sciences Po, a political science school in Paris. It furthered my approach of working across disciplines exploring the points of articulation between scientific and artistic fields to address societal issues.

Climate change is a consequence of our ways of perceiving the natural world as a resource to be endlessly extracted.

I am currently interested in how art might help redefine our relationship with the Earth. Livability on our planet is dependent on the presence of its many life forms. I think we are starting to see those new scientific understandings enacted in environmental conservation but we also need the arts to filter those paradigm-shifting ideas into our society and culture.

What is the film about?

For the Love of Corals is an artist film that follows Project Coral through the different stages involved in reproducing the corals behind-the-scenes at the Horniman.

It documents the daily labour of the team caring for these endangered beings as well as the corals themselves, encouraging attention to their intricacy. From spawning induced in lab-tanks replicating lunar and solar cycles, to the delicate IVF procedures, as well as the constant care required to keep the corals alive throughout their life cycle.

For the Love of Corals (2018) Trailer from Sonia Levy on Vimeo.

The film also includes shots of artefacts from the Horniman’s collections, such as the 19th-century Anna Atkins’ Photographs of British Algae Cyanotype Impressions. The opening sequence of the film confronts images of Atkins’ seaweed cyanotypes to close-up shots of the corals.

Anna Ricciardi’s essay on Anna Atkins, written for Edward Chell’s 2015 exhibition Bloom at the Horniman, really moved me. She says:

As we face an accelerating environmental crisis in this century, Atkins’ seaweed impressions surface with something like visionary timing, having slipped their privately-published moorings, to remind us about extinctions past and present, those erasures and absences yet to come.

It deeply resonated with an angle I wanted to take, a feminist approach to questioning the moment we find ourselves in. Climate change, ecological collapses: who are the most affected and vulnerable?

There is a growing sense of an interlaced precarity between humans and the other life forms with whom we share this planet. I think it might be crucial to develop a more inclusive sense of “we”.

A site like the Horniman Museum and Gardens, with its Natural History Gallery, is a powerful place to revisit our past, our ways of looking at and relating to nature.

It is also a compelling site to build and develop new connections as seen with the work of Project Coral.

The soundtrack was made in collaboration with sound artist Jez Riley French and involved many recording techniques made on site.

We used hydrophones and underwater microphones to capture the sound of some of Project Coral’s critters. Contact microphones picked up the resonance of surfaces around the Museum and the laboratory tanks. They are able to capture vibrations through contact with solid objects.

Adapted geophones, used to transfer ground movement to sound, allowed us to record the vibrations of the complex machinery sustaining the corals’ life. Electromagnetic signals emanating from the laboratory equipment were also captured with coil pick up microphones.

Jez also captured the sound of the skeleton of a coral dissolving, alluding to ocean acidification. These recordings, as well as music from composer Georgia Rodgers, are all part of the soundtrack composed for the film.

I also created a large-scale tapestry made from cyanotypes on fabric, which is part of the film installation. Titled Atkins Blue the work is a direct reference to Anna Atkins, an acknowledgement to her contribution in the history of science and art.

In conjunction with my exhibition, Obsidian Coast commissioned a reading list; We are All Bodies of Water, from scholar Astrida Neimanis.

What drew you to Project Coral?

I spent a spawning season with the team at Project Coral, through the invitation of Jamie Craggs. I was really fascinated by what they achieved.

To be the first in the world to successfully induce coral to spawn by recreating the environmental conditions of the Great Barrier Reef, as well as other locations like Singapore, in the basement of the Horniman, for me was a powerful and striking image.

Coral bleaching appears simultaneously as a sign of climate change, their death providing visual evidence of the rising of the sea temperature. As anthropologist Irus Braverman has put it, corals emerge as a ‘catalyst for action’* for many activists, scientists and artists.

Corals are stunning entities and coral reefs are some of the most beautiful ecological assemblages on Earth. The corals’ ability to perplex the notion of individuality, the distinction between self and other. There is something interesting about the figure of the coral and its capacity to blur the boundaries between organism and environment, expressing this idea that we are environments for others, as well as not being separated from our environment.

I have also worked with Project Coral to produce a short film, viewable on site at the Horniman’s Aquarium, as well as online. We worked with Jamie Craggs’ research footage to tell Project Coral’s ongoing work and explain its workings. I wanted the visitors to catch a glimpse of this vital research happening behind-the-scenes.

What techniques did you use to document the coral?

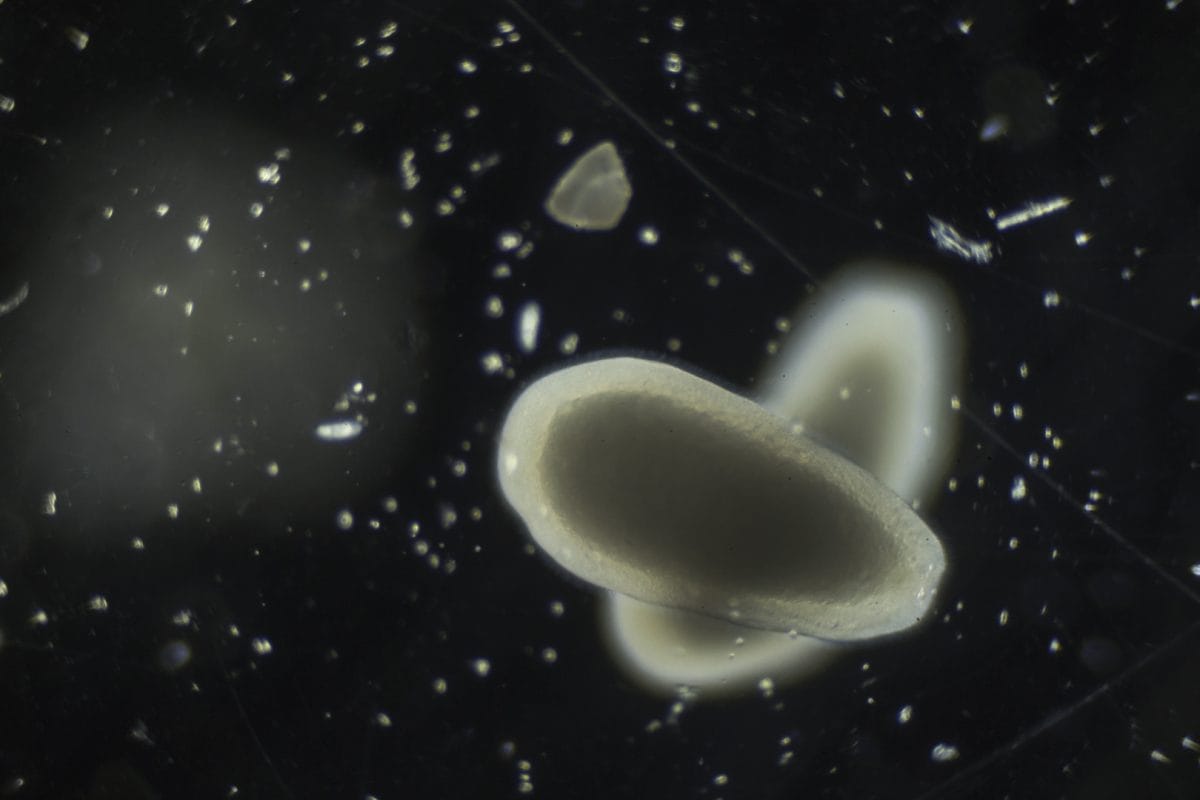

Some of the most extraordinary ways of filming involved coral larvae shot through a microscope. The larvae are no bigger than 1mm and I could see the cilia, the hair-like organs that propel them.

We documented the coral in other ways, such as the use of macro lenses and under blue light (actinic light), which produced a beautiful result. When pointed at corals it makes the symbiotic algae living within their tissue fluoresce.

We also collaborated with Jamie to make microscope time lapses of coral embryos development, as well as egg-sperm bundle dissociation.

What is your favourite moment from the film?

To film the juvenile corals I saw coming to life in 2017 as yearlings, but still no bigger than a thumbnail.

It was very moving for me to film them under blue light and see how they acquired their symbiotic algae. I also loved to plunge at the scale of those tiny corals and see the many critters and microorganisms living alongside them.

What is the next stage of this project and for you?

I am working with Obsidian Coast on a publication around the project, to be released in 2019. Additionally, I have a few screenings and exhibitions of the project planned in France, the US and Germany. But, what I am really interested in doing is to carrying on filming and progressing the project.

I would like to go to Florida where Project Coral is working in partnership with the Florida Aquarium Centre for Conservation. It would be really exciting to see how Project Coral’s methods are being used to help restore damaged reefs there.

For the Love of Corals is on view at Obsidian Coast, Bradford-on-Avon, until the 26 of January 2019. For the Love of Corals was produced with the support of Obsidian Coast and Fluxus Art Projects. Sonia Levy wishes to thank Jamie Craggs, Project Coral team and the Horniman Museum and Gardens for their in-kind support.

* Irus Braverman (2018), Coral Whisperers: Scientists on the Brink,University of California Press.