The enormous fossil – which comes in at 33ft long – is thought to be the first ichthyosaur of its species found in the country – Temnodontosaurus trigonodon. This species has only previously been confirmed in Germany.

Emma, Horniman’s Senior Curator of Natural Sciences, was part of the specialist team of palaeontologists which excavated the skeleton in August and September 2021, which was featured on BBC2’s Digging for Britain programme.

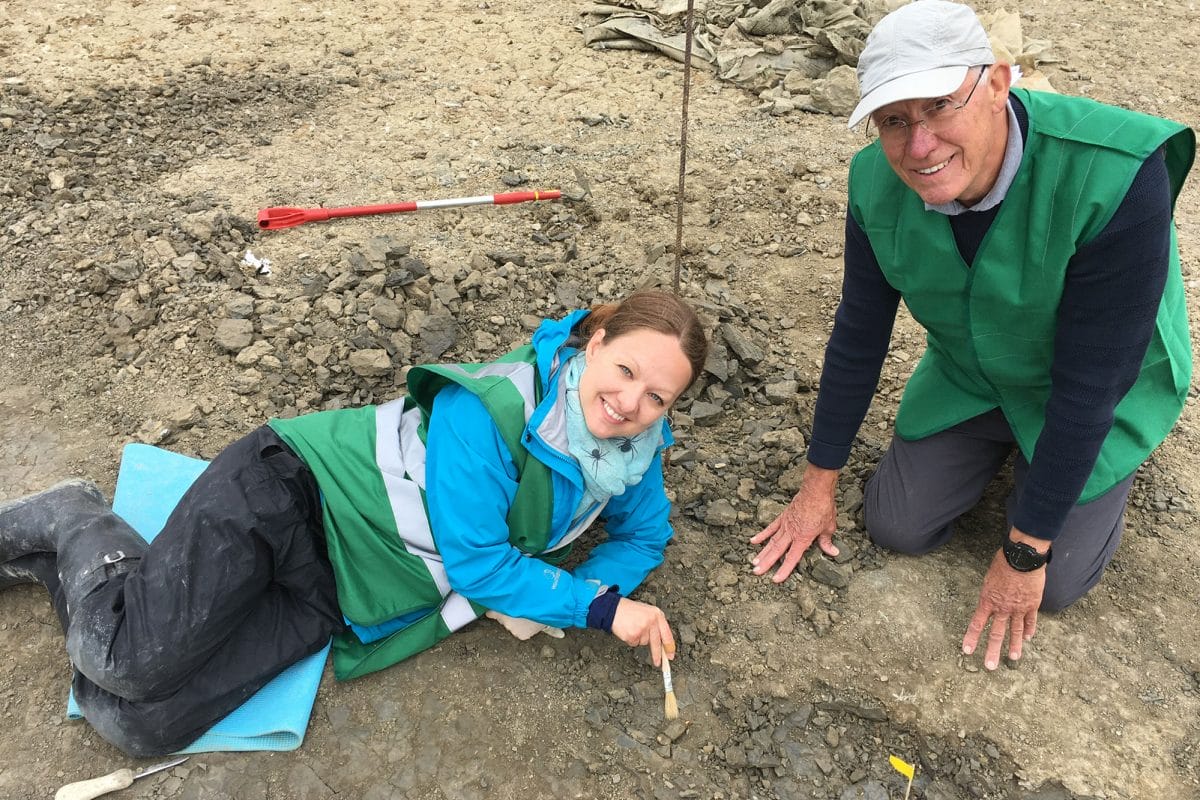

Dr Emma Nicholls as a scale with the enormous ichthyosaur discovery

I was asked to be on the team due to a combination of my background as a curator and my research specialism in marine vertebrate faunas.

The huge fossilised remains were discovered at Rutland Water Nature Reserve, owned by Anglian Water, by Joe Davis, the Conservation Team Leader at Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust. Joe made the discovery during routine draining of a lagoon island for re-landscaping in early 2021.

The find has been absolutely fascinating and a real career highlight, it’s great to learn so much from the discovery and to think that this amazing creature was once swimming in seas above us and now once again Rutland Water is a haven for wetland wildlife albeit a little smaller!

We asked Emma some questions about her experiences of the excavation:

Before this specimen was found, were there any clues about ichthyosaurs in this part of the country?

Isolated ichthyosaur vertebrae are found every now and then in Rutland and, in fact in the 1970s, two partial skeletons were uncovered when the artificial lake at Rutland Water was created.

So when the first few vertebrae of the new specimen were brought to the attention of my colleagues Dr Dean Lomax, Nigel Larkin, and Dr Mark Evans, it wasn’t a huge surprise. However, when they visited the site with Darren Withers in February and discovered that an entire skeleton may lay buried in the sediment, it suddenly became extremely exciting!

They uncovered enough of the skeleton at this point to identify it as probably being Temnodontosaurus trigonodon.

How was this confirmed?

As the skeleton was more fully exposed during the excavation in August and September, we were looking for particular diagnostic features such as notches in certain paddle bones along the leading edge of the fin.

What we found backed up the original identification, but we will have to wait for the skeleton to be further prepared before we can know for sure.

Why is this find so exciting?

Articulated and near-complete skeletons of large prehistoric vertebrates are INCREDIBLY rare!! Also exciting is that if we are right about the identification of the species, then this is the first confirmed record of Temnodontosaurus trigonodon anywhere outside of Germany, which adds to our knowledge of the biogeography of the species.

Who was on the excavation team?

The core team comprised four palaeontologists from across the UK; Dr Dean Lomax (University of Manchester), Nigel Larkin (University of Reading), Dr Mark Evans (British Antarctic Survey) and myself – from the Horniman Museum.

Dean and Mark are marine reptiles’ experts, whilst Nigel is a specialist palaeontological conservator. They secured funding and worked with Anglian Water, Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust and Rutland County Council to gain access and work out the logistics. I was brought on as the fourth member of the core team to (primarily) curate the site using methodologies set out in the Conservation Strategy devised by Nigel.

We also had help in excavating the ichthyosaur from a number of other people, including but not limited to PhD Student Emily Swaby; and Darren Withers, David Savory and Mick Beeson from the Peterborough Geological and Palaeontological Group. They were all vital to the effort and we absolutely couldn’t have done it without them.

What was your specific role?

It is crucial to document a site to ensure that no scientific data are lost as specimens are unearthed and removed.

Although we all worked on a variety of elements of the excavation as it progressed, my primary role was to use my 20+ years of curatorial experience to curate the site efficiently and accurately, according to specifications set out by Nigel in the Site Conservation Strategy.

Emma with fossilised remains at the ichthyosaur site

At first, the ground was very soft which meant the excavation was fast paced, and keeping on top of documenting the site was a challenge. But as changes in the weather meant that the ground went from soft sludge, to flaky mud, to hardened ‘concrete,’ the pace with which specimens were coming out of the ground inevitably slowed. Our muscles ached more, but the documentation was easier.

I also spent a lot of time on manual excavation, along with everyone else on site, which varied from gently peeling away layers of mud with a wooden stick, to shifting large amounts of heavy sediment with a spade. We were spending 12 hours on site every day – it felt like we were living and breathing ichthyosaur (which was fabulous, truth be told!) – but we were well looked after by staff from Anglian Water and Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust.

How did you manage with the pandemic?

The team had to be small for several health and safety reasons, not least of all covid. We all abided by a strict lateral flow test regime and wore masks when sharing vehicles or in the Visitor’s Centre. We also had enough hand sanitiser on site to bathe in!

What happens to the site now?

The specimen has now been completely removed from Rutland Water which is a relief as it is an active conservation area and important for migratory birds so we were under pressure to get the specimen out before the lagoon had to be re-flooded.

Image: BBC/Rare TV. Ichthyosaur remains at Rutland Water, as featured in Episode Four of Digging For Britain, airing on BBC Two at 8pm on Tuesday 11 January and available to watch on iPlayer afterwards.

The specimen is now safely tucked up into 11 plaster jackets, with smaller, isolated and fragmentary material kept separately in individual specimen bags.

It was decided to take the ichthyosaur away in large chunks, despite the practical complications of this (the skull block alone weighed over a tonne) because so much taphonomic information was preserved with the specimen.

The whole lot is being stored by specialist palaeontological conservator Nigel Larkin, whilst funding is sought to cover the costs of it being prepared and conserved.

Will you be involved in whatever happens next with the fossil specimen?

It is estimated that the skeleton will take around 18 months to fully prepare and conserve. However, we will be able to continue our research on the specimen before work is completed as certain diagnostic features will be uncovered along the way.

I will be involved in this research long-term and will contribute to any scientific papers that are published as a result.

It is extremely rare to be asked to be involved in a dig of this magnitude and importance, because discoveries of this nature are very few and far between. It was a privilege to be part of the team that excavated this specimen and I can’t wait to see what further secrets the skeleton will reveal.

Watch episode four of Digging For Britain, airing on BBC Two at 8pm on Tuesday 11 January and available to watch on iPlayer afterwards.

Funding for the excavation phase was provided by Anglian Water, Rutland County Council, The Geologists’ Association Curry Fund, The Palaeontographical Society and Museum Development East Midlands.

Image Credits:

- BBC/Rare TV

- Anglian Water