Pearl’s work is an important example of a decolonised essay format. She takes us on her research journey, brings into conversation exhibition spaces across time and space and tackles critical themes within the museum context.

Her living memories show the profound experience community members have when engaging with collections from their material cultural heritage, and the rich interpretations they add to uplift the collections for all.

The Horniman Museum and Gardens has always been an integral part of my childhood and formed a basis for my early learning, grounding, and perceptions of worldwide cultures.

Along with founder Frederick Horniman, who opened the Museum in 1901, I also recognise the people and my ancestors who have made it possible for me to do my work and research into the objects I have interests and passions about. My aim with my studies and new role at the Horniman as a Community Action Researcher of African and Caribbean collections is to uplift the unseen and hidden collections which lay dormant in storage, educate, liberate and break down existing barriers and divisions created by colonial borders.

Collections need to be equalised and accurately described, decolonised from their Eurocentric shackles, and enjoyed by all the way they should be.

Finding out that around 90% of these collections are not on display saddens me but also causes me intrigue as to why. Museums are trusted spaces but some objects housed by them need social reconstruction and re-education.

One of the things that I’ve always felt a sense of is primitive devaluation of objects in museum spaces. Objects from Africa and Caribbean Islands, if showcased alongside an object from Europe, are often described as being primitive and basic. Describing certain objects as primitive devalues them when shown alongside a European object from the same time period and same craftsmanship. This is completely wrong and gives a false sense of non-worth to the viewer.

Along with looking at the objects’ language and origins, I noticed a strong theme of absence at many museums when looking or researching for African or Caribbean objects and artefacts, which is not equitable for viewers of diaspora communities. But I would say that the Horniman did and could have more, but houses some of the best examples compared to the V&A which I feel sets a scene of unreachable and non-speaking collections.

Frederick Horniman opened his museum in Forest Hill originally as a big personal collection, possibly due to the timing of The Great Exhibition relocating to Crystal Palace / Upper Norwood / Penge. Apparently, his wife’s dismay at his hoarding of historical objects and ancient artefacts led to the Museum’s birth.

Growing up in the local surrounding area I feel compelled to write about both the Horniman and The Great Exhibition, but specifically focusing on the Human zoo exhibits. Horniman wanted his museum to remain free for the public, and it has remained that way even to this day. The Horniman family gained their wealth from the tea trade but Frederick Horniman remained a Liberal Abolitionist of slavery and wanted emancipation for all enslaved people.

My first object of interest is a headdress created and designed by Charles Harrington and named Master of The Midnight Robber.

Donated/catalogued at the Horniman around 1998, the headdress was originally part of the African Worlds permanent display situated on the lower ground floor (then) entrance section of the building. The headdress appears to be adorned and embellished with gold sequins, black and purple tassels, and velvet fabric. It depicts a skeleton made from papier-mâché and is painted white and black, sitting on a throne-like gold chair. The headdress is steeped with political undertones and storytelling.

The Midnight Robber is a key Carnival figurehead in Trinidad. The character represents and symbolises freedom of expression under colonial rule, resistance to oppression and – often at the Carnival – the person wearing the costume of The Midnight Robber will boast of the vengeance he will wreak on his oppressors.

The Ghosts of Carnival is what comes to mind when I view this piece as an adult but as a child viewing the piece along with my Father, I assumed it was Mexican and likened to The Day of a The Dead festival. The Midnight Robber is Americanised in terms of being like a cowboy or wild west rancher, in dress and behaviours acted out, but back in the 1700s, his character would have possibly been inspired by a Highway Robber.

If I were to re-catalogue the headdress I would add more information about Charles Harrington and his life as a Trinidadian carnival costume maker. I would include his political stance and also incorporate the history of The Carnival: the emancipation, history and origins leading back to 1498 and moving to 1962 which saw the end of British Colonial rule and the independence of Trinidad. I had a difficult time finding out more information on Mr Harrington due to lack of available information, perhaps this is partly why the exhibit lacks the relevant details. But I am not finished with my research and will continue to find the information the object should be accompanied with.

Amerindians had been settled in Trinidad some 8000 BC years before Christopher Columbus claimed to have discovered and claimed the Island. Amerindians originated from the Venezuelan mainland.

Trinidad changed through many hands over the years including the Spanish, Dutch and British. King James I renamed the Island Trinidad and Tobago in 1608 in the hopes that Tobacco plants would grow there and produce wealth. In 1773 Trinidad and Tobago became a British Crown Colony. I think the objects at the Horniman should include the past histories of the objects’ origins to highlight the struggle of the past and present.

Looking back at Carnival and its origins made me wonder whether we would still have Carnival today in Notting hill, Toronto, Canada and other Caribbean Islands and around the world if the many enslaved and freed slaves had not formulated their own Carnival back in the 1700s. It’s interesting that in the 1800s the British Governor of the Port of Spain in Trinidad tried to ban the playing of steel pans and percussion instruments. The ban came about as the instruments were deemed noisy and primitive. This oppression was eventually met with an uprising and, in 1881, the Canboulay riots occurred and the instruments were reinstated.

The French settled Colonisers started their own Carnival in 1783 but enslaved and even free slaves throughout colonial rule on the Island were not allowed to attend the grand event, so created their own event called Canboulay (from the French Cannes brûlée, meaning burnt cane).

111.241.22 Sets of gongs with divided surface sounding different pitches

Musical Instruments

My second object of interest is a pair of steel pan drums also from Trinidad.

The steel pan drums, although catalogued/donated in 1995, are more likely to be from the 1950s. The steel drums and pans were used as early back as the 1700s, and as mentioned, there was a riot response to the ban on percussion and steel drum instruments put in place during the 1800s. Stick fighting was also banned, and steel pans were replaced with bamboo sticks called Bamboo-Tamboo sticks which were also eventually banned in 1937. Steel pans were replaced for a short while with sticks that had to be banged on the ground, and sound-wise were not as powerful as the steel pan.

Calypso music was developed specifically in Trinidad in the 1700s and originates from West African Kaiso and Canboulay sounds. The enslaved West Africans were made to work the plantations and were stripped of all cultural connections to homelands. Calypso music was a secret and I think a sacred sound and song, with codes and insults towards the French slave owners who banned speaking and communication between plantation workers. Calypso was used to mock the slave owners and often performed by a griot and nowadays known as a Calypsonian.

In 1937, steel dustbin lids, frying pans and oil drums were used to create a Calypso sound. A steel pan innovator named Winston ‘Spree’ Simon helped in pioneering what is now known today as the steel pan, and specifically the ‘Ping Pong’ steel pan.

Lord Kitchener – a Calypsonian musician – was also a pioneer in making Calypso more mainstream across the globe. More recently a female drum arranger named Michelle Huggins-Watts was the only woman to win the Islands Panorama competition along with her band the Valley Harps. Calypso and the playing of steel pans seem largely dominated by men, and for a woman to play was deemed socially unacceptable in the past.

The creation and process of the steel pan is relatively simple but requires skill and is mesmerising to behold. The process consists of hammering a bowl shape from the top of a steel barrel or oil drum, notes are then etched out in placement areas and a drum maker then hammers the steel to create the notes. Finally, the drum is tuned with a strobe tuner and thus becomes ready to use, although there are some variations on the process.

Carnival and Calypso are in some upper echelons of the Caribbean islands, frowned upon and people attending carnival looked down upon and considered hooligans. I find this interesting and sad that colonialism is still present and holds control over some indigenous communities.

It would be great if the steel pans, Charles Harrington’s hat, and any other Caribbean items, could be redisplayed with the origin and histories that they hold as I feel the write-ups they currently have do not do them justice.

During the changeover of the gallery, both items were removed and put to sleep in storage where they still lay now. There is no specific area in the Museum that links the Caribbean objects together as a whole but I strongly feel there should be.

If there were to be a Caribbean or African collection I would hope it to not represent the non-material culture but the material culture and history, with non-derogatory examples.

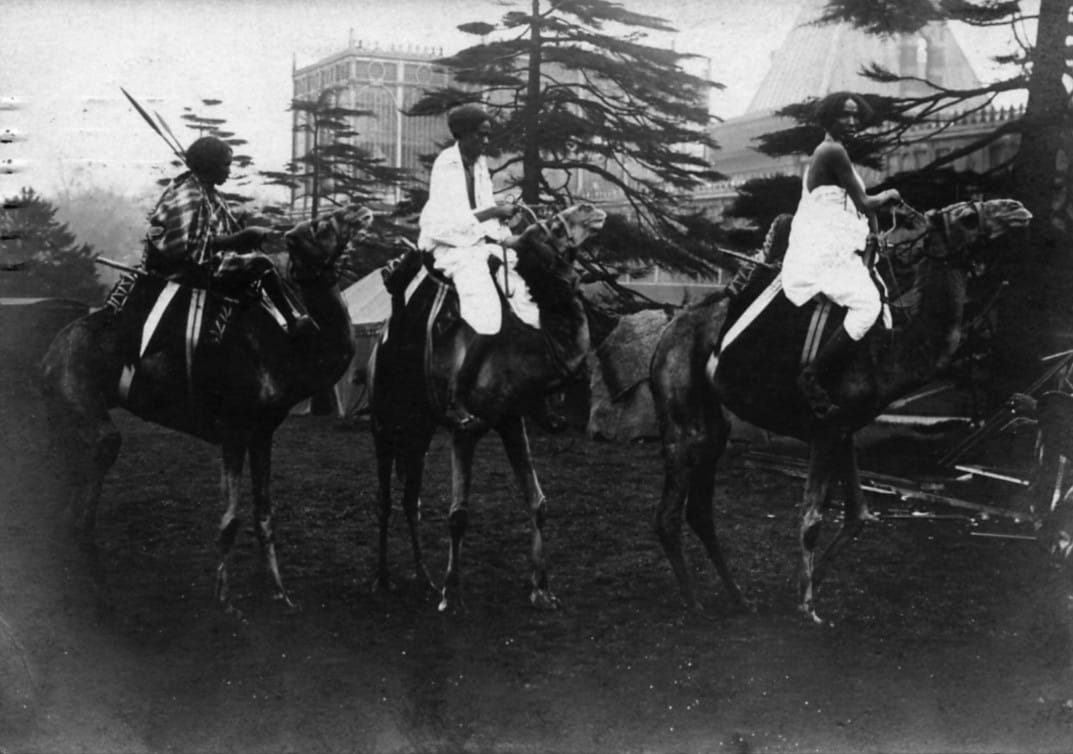

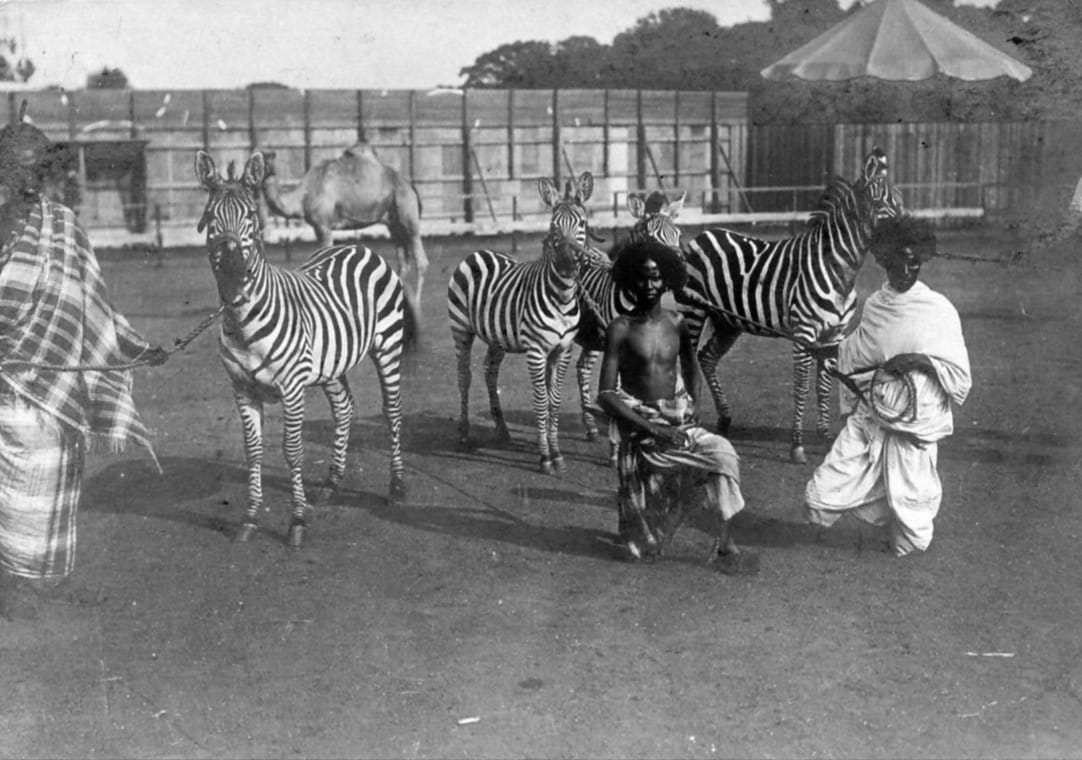

The Festival of Empire in 1911 had a live human exhibit called People of The Commonwealth in Crystal Palace Park. This was the final placing and resting place of The Great Exhibition which was originally in Hyde Park London from 1 May 1851 until 15 October 1851.

The Festival housed a number of imperialistic village attractions from 1854 onwards until its destruction from a fire in 1936, like The African Village, India, Canada, Australia and Native America. My research into the subject of The Great exhibition was somewhat easier, as I already know quite a lot from personal interest and local positioning.

I was helped greatly with the imagery from local historian, Crystal Palace and Great Exhibition enthusiast Melvyn Harrison, who is also a founding member of The Crystal Palace Foundation. With the Horniman being so closely related to the Crystal Palace I think it would be interesting to have a linked exhibition celebrating and looking in more detail at the subjects raised within my writings and research. Melvyn would also be more than happy to help with the ethnographic imagery that he holds. My father also donated some of the images contained within my research report, the research into The Great Exhibition and The Colonial and Indian Exhibition was easier than my ongoing research into the African and Caribbean objects at the Horniman but I hope the barriers I faced change in the future.

Ira Aldridge was a respected Shakespearean actor and the first person of colour to play Othello in 1833 in London.

He left America where he was originally born in 1807 to pursue an acting career in the UK as he was not allowed to do so in the US. At times he faced hostility, ignorance and racism. I know that Queen Victoria was a patron of his productions and towards the end of his life he too lived locally in Upper Norwood on Hamlet road.

Ira died in 1867, and I wonder if he himself would have visited The Great Exhibition and how he may have reacted to the world village displays?

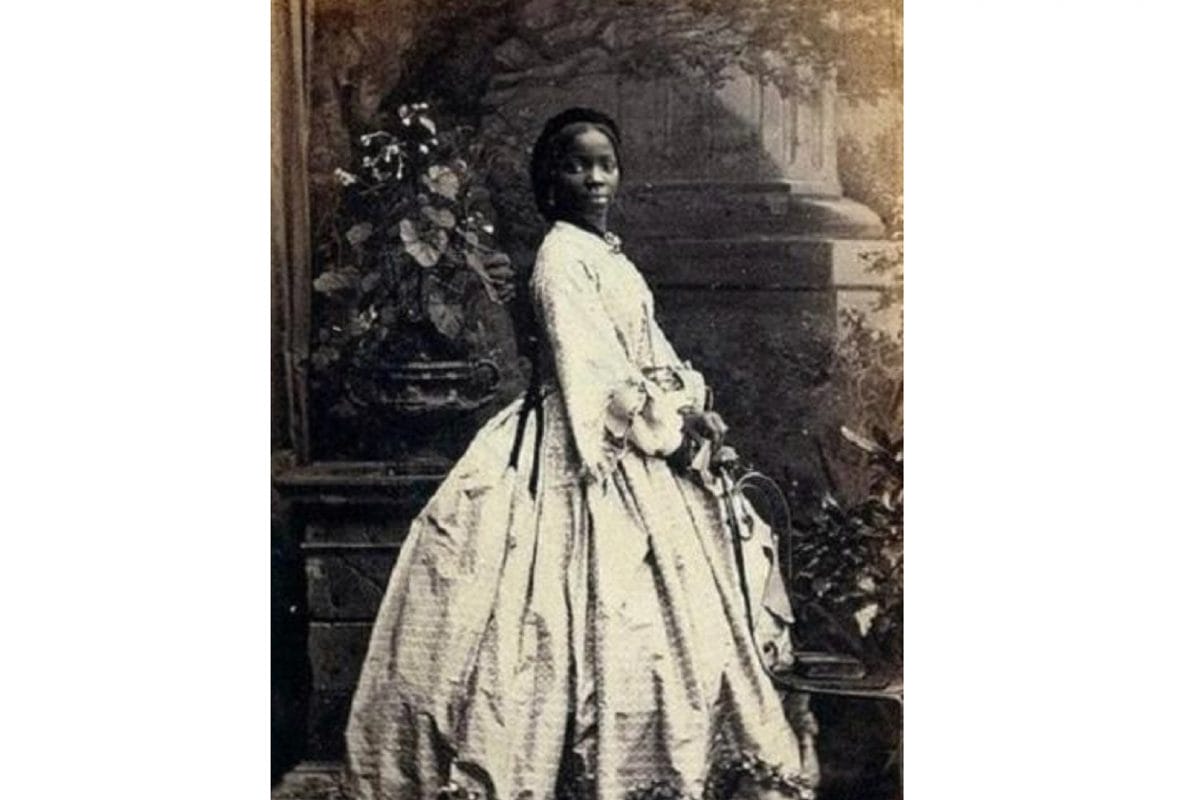

I also wonder if Sally [Sarah Davies] Bonetta Forbes ever visited The Great Exhibition.

If so, she would have been very young but already colonised into Victorian fashions. I wonder how she would then, in turn, perceive the African villages. Sally, born in 1843 in Yoruba West Africa, was captured at the age of five during the Okeandon War.

Placed in captivity and held to be presented to any guest of importance, Sally was taken by Captain Forbes on board the HMS Bonetta in 1851 where it set sail for England. Captain Forbes asked King Gezo if he could have Sally as a gift and his request was granted.

Sally lived at first with Forbes and given the name Forbes Bonetta after the Captain and his ship. She was cared for and then presented to Queen Victoria as a gift at Windsor Castle. I believe Victoria was quite fond of Sally and renamed her Sarah and had her privately educated. Although fond of her, Victoria described Sally’s daughter Victoria:

Saw Sally Davis’ little girl, Victoria who is now 8, and wonderfully like her mother, very black and with fine eyes.

Sally died in 1880 aged only 37, after suffering most of her life from poor health attributed to the change in climate. Reading that she had tuberculosis, it is more likely in my opinion she died due to poor medical expertise and assistance for the treatment of the disease. She lived in a warm climate at her time of death and it is more thought that cold weather exasperates the condition, this and overcrowding in poorly ventilated living accommodations.

Upper Norwood and Crystal Palace are steeped in rich history and some myths surround the area.

Myths can also surround museum objects, but it is true and fair scripture that should surround them accompanied by input by communities, along with the Curators’ input. It is very important to have real living memories to accompany the objects we view, and to build up a picture of how the object came to be in our gaze.

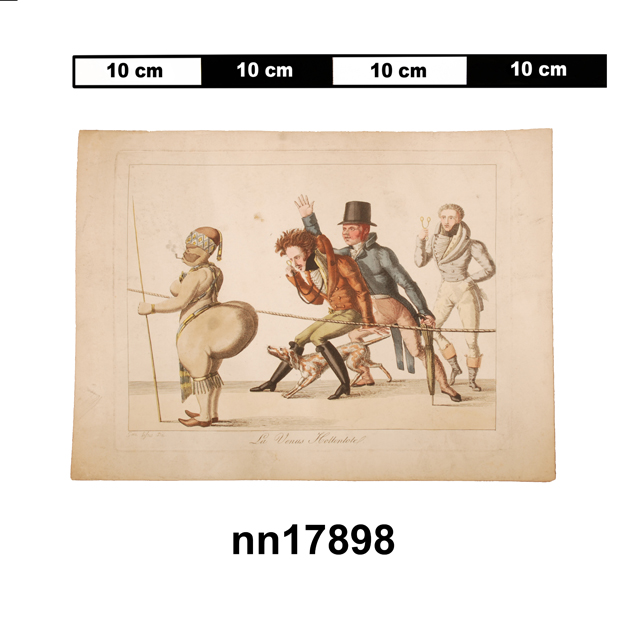

These human zoo expos were commonplace up until the 1950s, in some parts of the world and The Great Exhibition was not the first. We only have to look at the disturbing history of Sarah Baartman – named at birth as Sshura in around 1789.

Originally from Khoisan parents in South Africa, she was raised on a colonial farm near Hankey and sold to a Dutch enslaver called Pieter Willem Cezar. Sshura, as I prefer to call her, was treated like an animal. She was forced into a second renaming of Hottentot-Venus and subjected to a life of human gaze, abuse and sexualised primitivism display for the rich to spectate at.

She performed in both London and Paris, cases like hers were not unusual during this time period. Even after her sad death in 1815, her body was sold to William Dunlop who worked as a surgeon. He dissected her and had her buttocks, brain, genitalia, skeleton and reproductions organs displayed in London and in Paris at The Musee de Homme.

Her genitalia, reproduction organs and brain were thought to have been put on display to show Europeans the intellectual equality and sexual differences to that of a western imperial female. I find reading about her life and story very sad and unsettling, and I am glad that her remains have been laid to rest near the Gamtoos Valley after outcry from Nelson Mandela and the public upon hearing about her in 1974, although not laid to rest until 2002.

Human remains should not be displayed and I believe as museum curators and researchers we have a duty to reunite human remains back to places of origin if not being used for specific research or authorised display. I believe this relates to the ownership and co-ownership of objects in museums, objects like people cannot and should not be owned, although within a museum setting we see the objects as being owned by the Curator, or the original collector or buyer, but never as belonging to the culture that they originate from.

Black face paint at The Festival of Empire in 1911, was also seen and documented in an image of Zulu tribesmen from South Africa.

They were painted with blackface to eradicate any sense of own identity or differentiating skin tone, liking them as the same person pictorially. Treating people like objects rather than humans, blackface was commonly used at these expo type events and again seen at the 1911 Coronation of George V in London.

If we look at the Irish expo section – or even the English – there is a distinct difference in setting. Many of the human settlements of The Festival of Empire included indigenous people from Somalia, South Africa, Canada, Australia, South America and Central Asia. Primitive idealism was perpetuated through European colonialists with ethnocentric preconceptions, and is something that should not be continued now when displaying objects from Europe, Africa or anywhere.

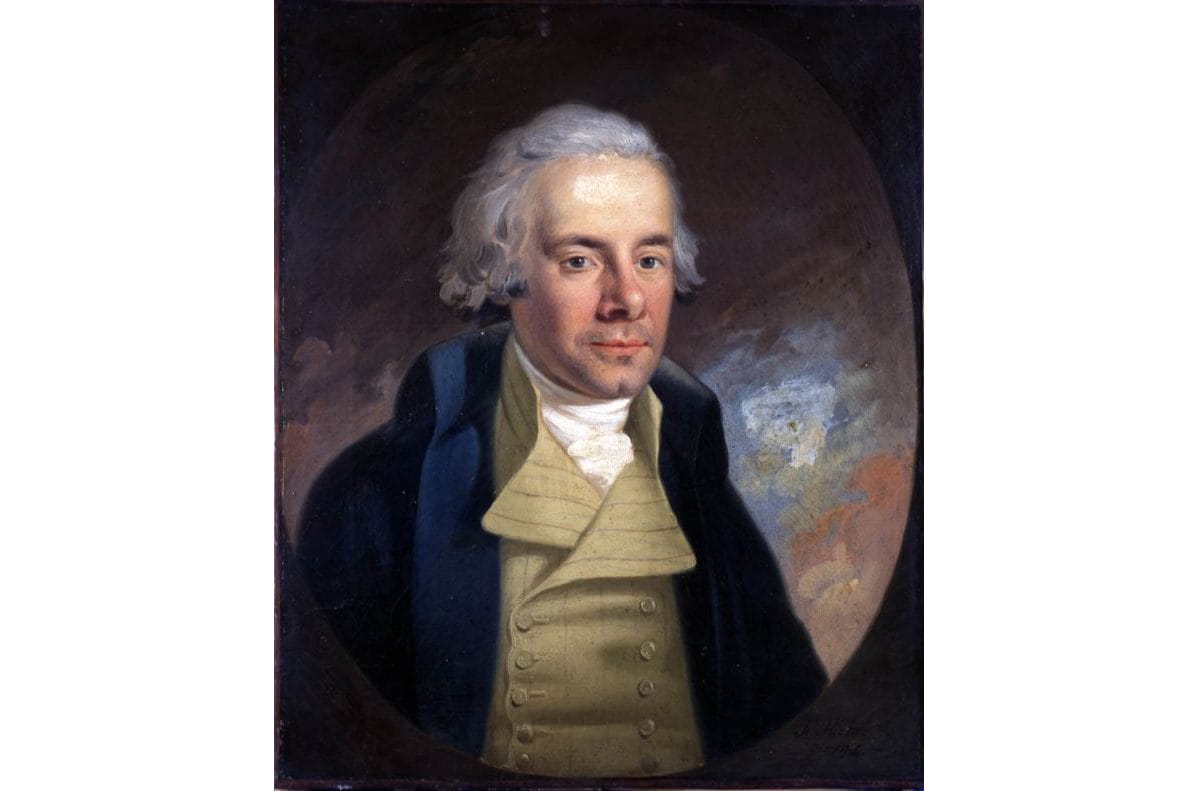

Growing up, I frequented the William Wilberforce Museum in Hull.

William, like Frederick, believed in the abolition of the enslaved people in the United Kingdom and the Empire during the early 1800s. William died three days after slavery in the British colonies was abolished in 1833.

Visiting his museum in Hull as a child always filled me with joy and pride, and I guess I felt the same when visiting the Horniman knowing that both men were active in the abolishment of slavery, and at the same time creating and hoarding collections that would serve the public purpose and educate in future years. Being an adult now I still have great respect for both men but feel the collections housed need a new speaking voice and further updates. I think that more items from African Caribbean origins need to be on a permanent display.

Living memories of the Horniman, present and past

I frequented the Horniman Museum and Gardens as a child with my parents. In fact it was probably the first museum I had ever visited, as it was so local to me. I grew up in Crystal Palace so am well versed in its histories and mysteries, on first impressions I looked at the front entrance of the Horniman turret as being very grand and ancient. It evoked a sense of excitement and intrigue and I often believed that Ancient Egyptian mummified remains were being held in the turret.

My favourite objects were those in the African Worlds gallery, as well as natural history, costumes and the Aquarium, as no other museums seemed to have living creatures: that made the Horniman unique to me. I also remember the reptiles and my sister, Daniella Hodgson – who is slightly older than myself – remembers riding on a giant African Spurred Tortoise as a child.

The Horniman holds many happy memories for myself and many others. It has been a privilege to contribute to this project. I spoke to my friends and family about the museum and what it means to them first memory to last. My father, Nicholas Hodgson, remembers visiting at the age of five during the mid-1950s to early 1960s, and he was always fascinated by ethnic masks and offended by things he deemed ugly, like the natural history taxidermy and wet specimens. Unlike myself who enjoys once-living specimens pickled in ethanol and formaldehyde.

My father said that he would gaze at the 1966 Native American Navajo sand picture for hours in a trance-like state. The picture was created by Fred Stevens, a Navajo singer, and was always an unfinished piece of work but one that I think many have enjoyed over the years and remember.

After some years in storage, the painting in 2004 was lovingly restored and displayed once again in pride of place. He said that there has always been a good variety of objects to hold the interests of all, but he always wondered how much more of the ethnic collections were available but not on display and that the objects on display seemed loosely shown and not strongly collated.

Nicholas still loves the Horniman as much as he ever did but he also agreed that perhaps the museum needs to be more accessible to all, and hopes that this will become a reality for future generations.

My mother, Nadine Hodgson, arrived in the UK in the early 1970s from New York. Before visiting the Horniman she had only really visited the American Museum of Natural History.

She visited the Horniman in the 1970s and had a keen interest in musical instruments, African art, anthropology, taxidermy and textiles. She visited on her own and then, after having children, her purpose for visiting was to educate. She remembers the museum always being well-presented but thought that the accompanying literature for some items seemed lacking and somewhat made up, she believes in accurate information to do the objects justice. She too has seen many changes over the years but still absolutely loves visiting and looks forward to positive changes.

My father is English and European, and my mother is of Caribbean mixed heritage. So myself, being of a mixed heritage, feel very strongly about balance in all areas of society and this should reflect within the museum space which is often a trusted space by many who enjoy and use it.

My goal as a community researcher would be to release hidden collections even if just on a temporary rotating basis to ensure all are shown.

I have seen the collections change over the years and not always positively. I understand the museum needs to evolve to keep up with modern-day interests but it should remember not to hide away objects that lay the foundations for the formation of the museum.