Leaning my head back over the sink in my Auntie’s bathroom, the acrid smell of the hair relaxer generously applied to my hair, mingled with the smell of burnt sugar from the Tate and Lyle Factory which loomed outside the window.

Every few months, I would hop on the tube to the Docklands to have my hair done at my Auntie’s house-come-hair salon. Made up of a cocktail of hydroxides, the prickling sensation of the relaxer would grow to an itch, then a burning until Auntie gently washed the cream out with cool water, bringing a wave of relief. Her bathroom was filled with bottles of Pink Oil, tubs of Blue Magic, piles of combs, curlers, rubber bands and in the corner, boxes of hair relaxer. Stacked high, each colourful box boasted “guaranteed results” with pictures of smiling Black women waving their sleek, shiny, straight hair.

I relaxed my hair at 16 and continued treating it for about seven years. Relaxer is known as “creamy crack” for a reason – once you start it’s pretty hard to stop.

As a teenager, having straight hair that was easily manipulated gave me the freedom to cut a variety of terrible fringes and experiment with high, swishy ponytails. With all the freedom that it gave me, relaxing also caused a lot of damage such as split ends and the occasional burn on my scalp.

For the hair shop installation in Hair: Untold Stories, I chatted about hair relaxing with Ebuni Ajiduah. Ebuni is a trichologist (a hair loss specialist), creator of the (very funny) podcast, Snatched Edges and regular contributor to gal-dem’s column, Afro Answers.

There’s certain things when it comes to hair and health that I think shouldn’t be available for public use so freely, and I think relaxers are one of them because they are very, very strong chemicals. People say that they contain endocrine disruptors, which are basically chemicals that mimic your body’s hormones and so they can make your own levels fluctuate. Black women have more menstrual issues, especially fibroids, PCOs [polycystic ovaries] and what’s also common is relaxer use. Studies I’ve seen have been replicated in the US and in Ghana, but they’re more like questionnaires. It needs to go one step further [...]

Our hair and our health are tightly wound, but with Black women there’s also a stigma that follows us where because of our hair practices we are to blame for the health issues we might face. In her interview, Ebuni goes on to say that the fault should really lie with manufacturers making those products.

Whether it’s relaxed, natural, weaved, dyed, braided or covered with a wig, Black people wear their hair in a variety of styles for an infinite variety of moods and motivations. For this exhibition I wanted to reflect just that – the diversity in our lived experiences as Black people and particularly as Black women and non binary folk.

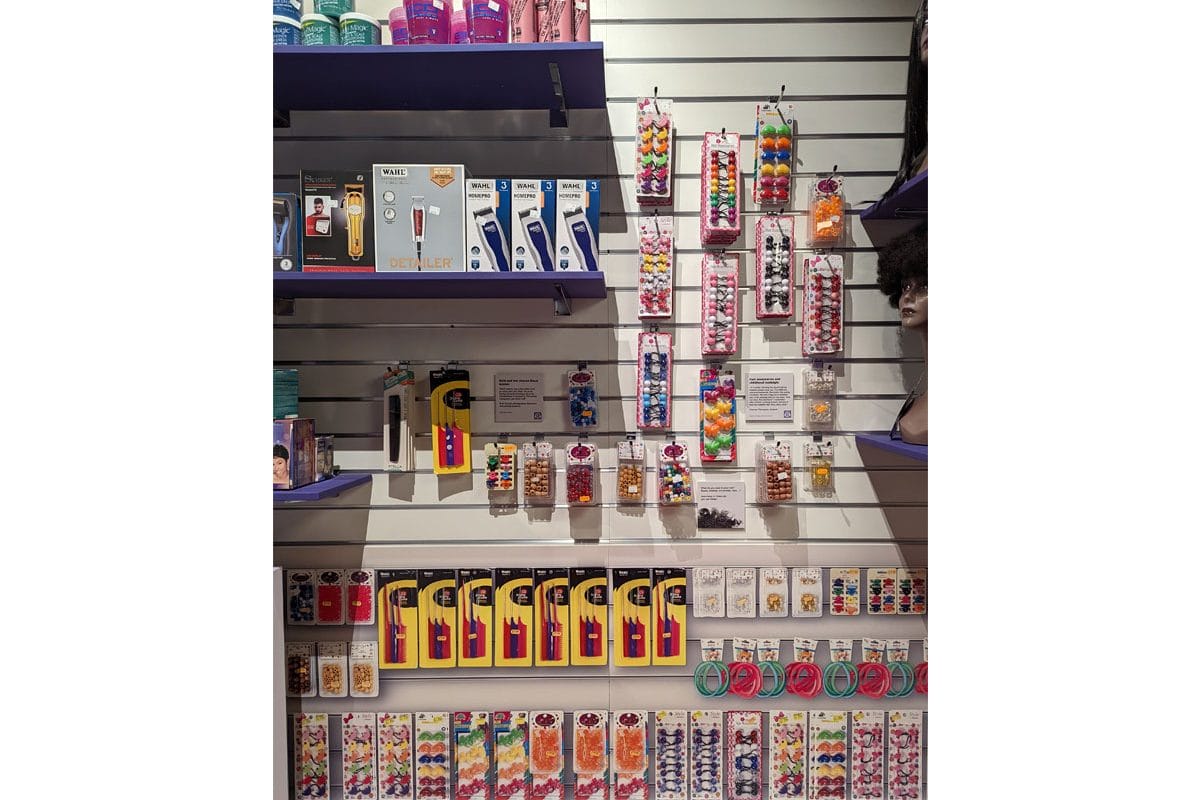

Black British women are reported to spend about six times more on their hair than white British women. The afro hair care business in the UK was worth an estimated 1.29 billion pounds in December 2020. Despite this, most hair shops on the high street are not owned by us.

When I nip to the shop to get my monthly supply of conditioner and oils, I’m usually served at the till by a south Asian man. South Asian owned Pak’s Hair & Cosmetics (or Pak’s as it’s usually known) is arguably the most well known afro hair shop with nine branches across London.

Instead of the high street, many Black women have carved out a hair care space online. Businesses like Afrocenchix and The Afro Hair & Skin Co have flourished, and national events like Black Pound Day are driving people to support Black business.

It’s worth asking, what does this mean for the high street? And who is really profiting from Black hair? The till in the installation represents the complicated web of purchase power and at the audio point on the till, you can hear the thoughts of Cyndi Anafo who is the co Director of Peckham Palms, a hair and beauty retail space led by Black women.

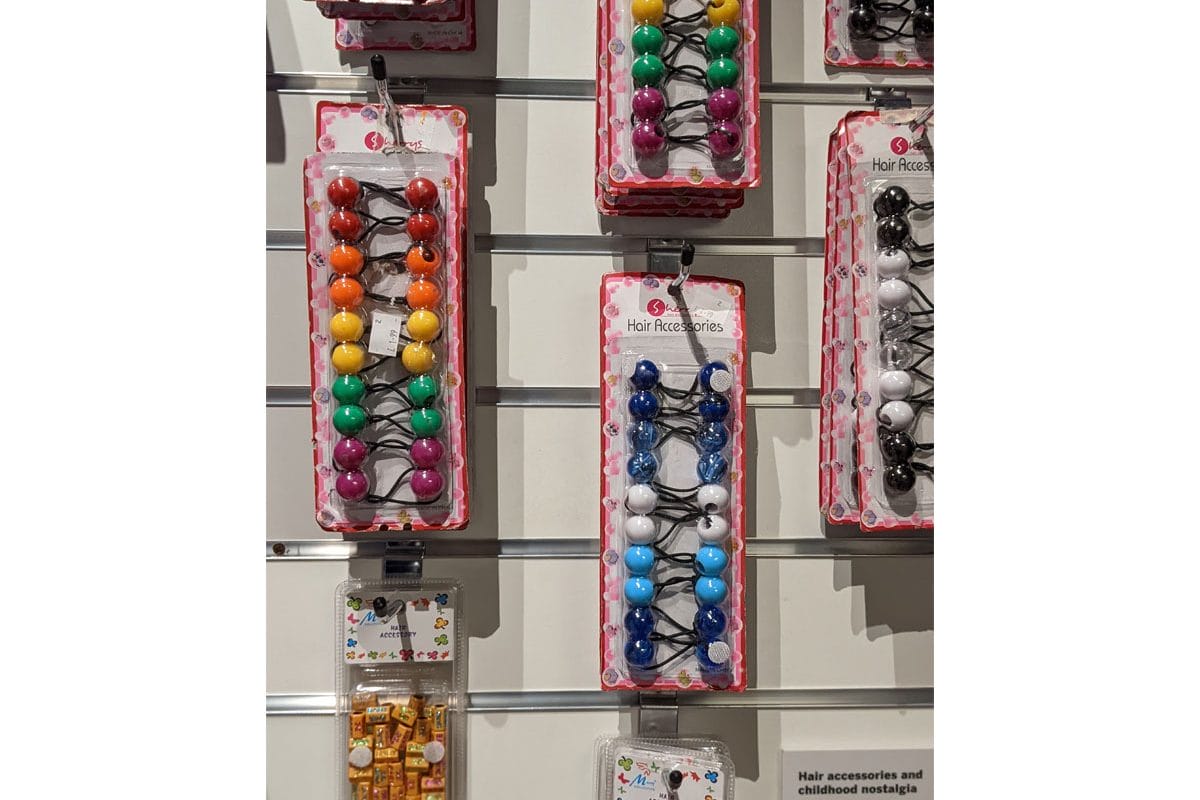

Behind the till, you’ll find a wall of hair accessories. As a child, the accessory section of a hair shop looked almost as good as the pick ‘n’ mix section of Woolworths (nineties kids will understand). Packs of multi-coloured beads, rows of scrunchies adorned with diamantes, butterfly clips lashed with glitter, hair bobbles shaped like glittery pink dice – they had it all! There’s something irresistible about rows of delectable looking hair treats, and looking at them makes me feel instantly nostalgic. I remember running around the playground in primary school, shaking my head to and fro to hear the bobbles go “clack” and the sudden pain when one of them pops you in the eye.

I remember the large case mum hid in her cupboard that was full of colourful hair bobbles, ribbons, different coloured thread and curlers. I remember the pride at posing for my school photo with my twists adorned with beads. Charnae, a south Londoner and student who lends her memories to the exhibition, reminisces about picking out her favourite bobbles to wear for church, as part of her Sunday best.

I love the way that creatives like Kay Davis and Nikiwe Dlova draw on Black hair art so beautifully in their work. That kind of joy and playfulness is as, if not more, important to me than anything else for Black women.

In the hair shop you can also hear the words of Ruth Sutoyé, a cultural producer and artist talking about what it’s like being a low shaven/bald woman, gender and the beauty expectations that Black women experience.

Over in the wig section, Darkwah Kyei-Darkwah a non-binary artist, content creator and presenter, explains the freedom, creativity and power that comes from wearing wigs and the different fantasies they can fulfil.

Ebuni, Cyndi, Charnae, Ruth and Darkwah are five individuals with their own experiences. I like to think of the hair shop as a library. Each object in the shop holds a different biography and tells a unique story. From gender to creativity to economics, the factors that influence how we interact with our hair are incredibly diverse – even though the stuff growing out of our heads might seem everyday.

All the stories featured in the exhibition can be found in the Hair Shop zine, available for free in the museum or on Korantema’s website.