Roy started by telling us that the ‘folk’ usually used common, everyday plants, growing in their domestic gardens or in local hedgerows. They did not seek out rarities. When medicine became commercialised practitioners could not advise their clients to use rotten apples or old cabbage leaves; they claimed that their medicines contained ingredients brought at great expense from distant lands. Even if folk medicine did not improve patients’ health it gave carers something to do, rather than stand around and helplessly watch their loved ones suffer.

As Roy has been collecting plant folklore for several decades many of the remedies he mentioned were from his own collections, remembered by people during the last 40 years.

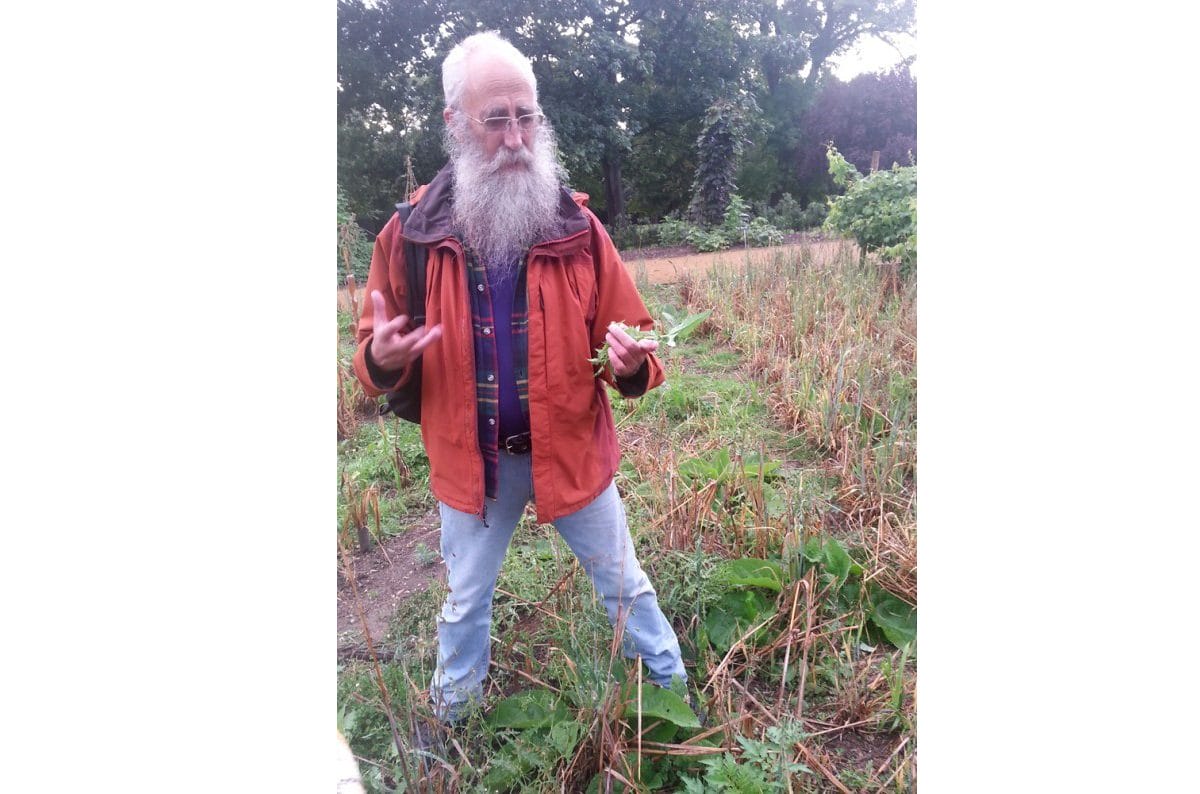

In the Horniman Gardens vegetable patch he talked about small potatoes (preferably stolen) which were carried in pockets to prevent rheumatism. Sometimes it was believed that carrying a small potato would ensure general good luck.

In the 1930s in Scotland a poultice made from carrot grated into lard was used to treat chilblains. It worked, but it did ‘ruin one’s slippers’.

Small onions were heated and placed in ears to alleviate earache. Raw onions were rubbed on to insect stings, and syrup made by covering sliced onion in brown sugar was used to treat coughs and colds, or as a general cure-all.

It was widely believed that onions attracted germs, but opinion varied as to whether or not this was a good thing. Some people thought they absorbed germs and therefore placed onions around their homes to keep plague at bay, or around their cowsheds to prevent foot-and-mouth disease. Others thought that a cut onion would attract ‘all the bad from the air’. It is said that during the First World War bullets were sometimes rubbed on onions in the belief that wounds caused by them would fester and be difficult to cure.

Garden weeds also had their uses. Groundsel boiled in lard treated constipation, and in Ireland dandelion was valued for treating a wide range of ailments, including kidney troubles, indigestion, jaundice and weak hearts. Three meals of nettles each spring were said to clear the blood and ensure good health.

Roy explained that before frozen and imported vegetables were available there was a ‘hungry gap’ each year, when vegetable plots were almost bare, so gathering nettles, which are rich in trace minerals and vitamins, would undoubtedly add nourishment to an impoverished diet. Before the discovery of antibiotics nettles were added to the food of young turkeys to try and keep them healthy. Being stung by nettles could prevent rheumatic and arthritic conditions, or, when such conditions already existed, would cure them.

Raspberry leaves, from the fruit garden, were made into a tea taken during the last month of pregnancy to ease labour pains, while Irish people used gooseberry spines to treat styes. The ways in which this was done varied, but it was usually considered necessary to bury the spine to make the stye disappear.

Although people didn’t usually cultivate blackberries in their gardens no doubt they encouraged the growth of brambles which produced particularly succulent and juicy fruits in their hedges. Crawling under a rooting bramble arch was considered to be a cure for a range of ailments, including rickets in Wales, whooping cough along the Welsh border and elsewhere, hernia in Somerset and blackheads in Cornwall. Usually there was some sort of ritual attached to these cures: sometimes people had to crawl under the arch at sunrise on seven consecutive mornings. If the cure failed this could probably be explained by remembering ‘well, we were a bit late on the fifth day’ or something similar. In Ireland people crawled under such arches to obtain good luck when playing cards.