When I first joined the Horniman in November as a Collections Management and Documentation Trainee, I was working at the off-site storage facility where much of our collection that is not on display is kept.

However, since January, I have been working largely on-site at the Museum decanting the specimens on the balcony of the Natural History Gallery as part of the Nature + Love project. Through this process, I have learnt so much about all the different natural history specimens we have encountered, as well as the many different packing techniques that are used in museums for safely caring for the collection.

Decanting the specimens individually and spending time with each of them when packing has allowed me to appreciate the incredible specimens we have in our collection, and to handle them and see them up close has been a wonderful opportunity.

The creative aspect of packing is something I have particularly enjoyed, as every packing solution for an object or specimen is different, and they all come with their own unique challenges.

I knew from early on into decanting the Natural History Balcony that I wanted to pack the 19 bird heads that were on display in Wall Case 57.

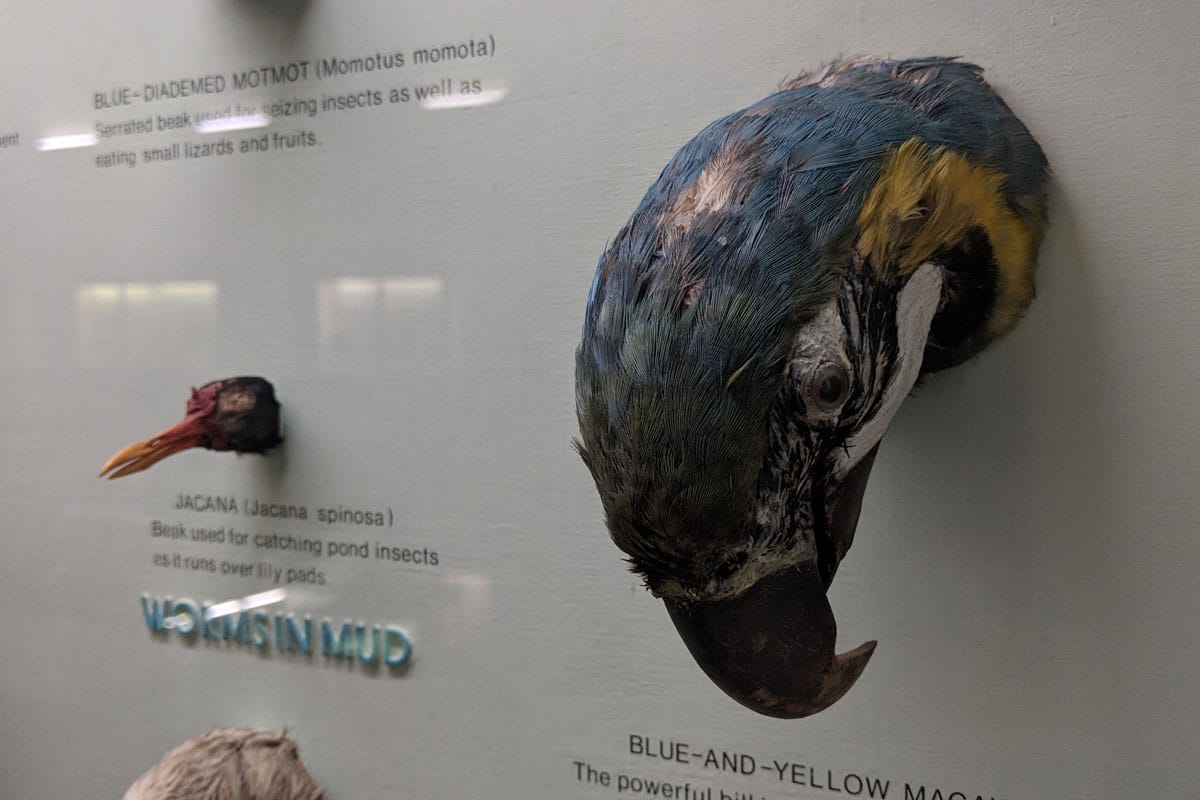

The bird heads made up a display educating visitors on how birds have developed different shaped beaks in response to the foods that they eat, and these specimens were being used as examples of these evolutionary developments.

I was drawn to these specimens partly because I was excited for how they would look displayed all together in a box, looking up at the person lucky enough to remove the lid and take a peek inside, and partly because I am a big fan of delicate, intricate packing of small specimens, so this seemed right up my street.

I also remembered seeing and enjoying the display of bird heads from when I first visited the Horniman, so it was nice to pack something that had stuck in my memory from that moment.

However, having only been working at the Museum for three months, and having at that time only been decanting and packing specimens for one month of that, I initially had no idea how to begin going about packing these delicate bird heads.

After taking them off display, we found that they all had thin cork backings to them, which became a useful basis from which to formulate a packing plan of action.

After getting approval from the Conservation team, we decided to extend these cork backings with foam, so we had a larger surface area to work with and so that the feathers of many of the birds could hang down around the backing without getting crushed or damaged in any way.

I cut out small bespoke circles of foam for each of the different birds by placing the bird head on a scrap of foam, drawing around it in pencil and cutting these circles out. These were then pinned onto the cork backings of the birds, before being pinned in place into the bottom of the box.

Although this was secure enough to ensure that the bird heads did not fall over, this was not a good enough packing solution to guarantee that the bird heads survived the van ride to our storage facility. We had to make sure that nothing was going to jog them out of place.

The main issue we had at this point was balance, as most of the birds were very beak-heavy, and so were either already leaning forward or had the possibility of leaning forward simply due to this weight imbalance.

The rather fashionable solution we found to this problem was to create little foam ruffs for all the bird heads by cutting slits almost all the way through a strip of foam, before wrapping this around the half of the bird head that was carrying the most weight.

This was a technique we had seen the Conservation team using when packing some more delicate specimens, and it worked very well. For the birds with particularly long beaks, I made beak supports out of foam covered with Tyvek, a very soft and non-abrasive material that would not cause any damage to the birds’ beaks. I spent a total of about a day and a half working on these bird heads and was very pleased with the outcome.

Another issue that the bird heads brought up is that only one of the nineteen birds was recorded in our online database and had been previously given a unique museum number.

Every object and specimen in our collection needs to be allocated a unique museum number so we can track its location and make sure that it is stored correctly. The only bird head with a number was the blue-and-yellow macaw, and the notes in our database stated that this bird head had come from the S. Prout Newcombe Collection. This information had been traced back to the Accession register, where the entrance of this particular bird head into our collection had been recorded with its scientific name of Ara ararauna.

However, all the other bird heads had no records that we could find, and so it was necessary to provide them with new unique museum numbers and give them a new record.

Since packing the bird heads, I have packed many other unusual specimens, whether in shape, size or fragility, and have learnt so much more about the many specimens we have at the Horniman, as well as how best to pack them. I cannot wait to continue the decant of the Natural History Gallery, and keep learning about the incredible and varied specimens that make up our Natural History collection.

Part of our Nature + Love project, which is made possible with The National Lottery Heritage Fund, thanks to National Lottery players.