Use the left and right arrows to read through David’s piece above, or find the article in full below.

How do you collect a tattoo?

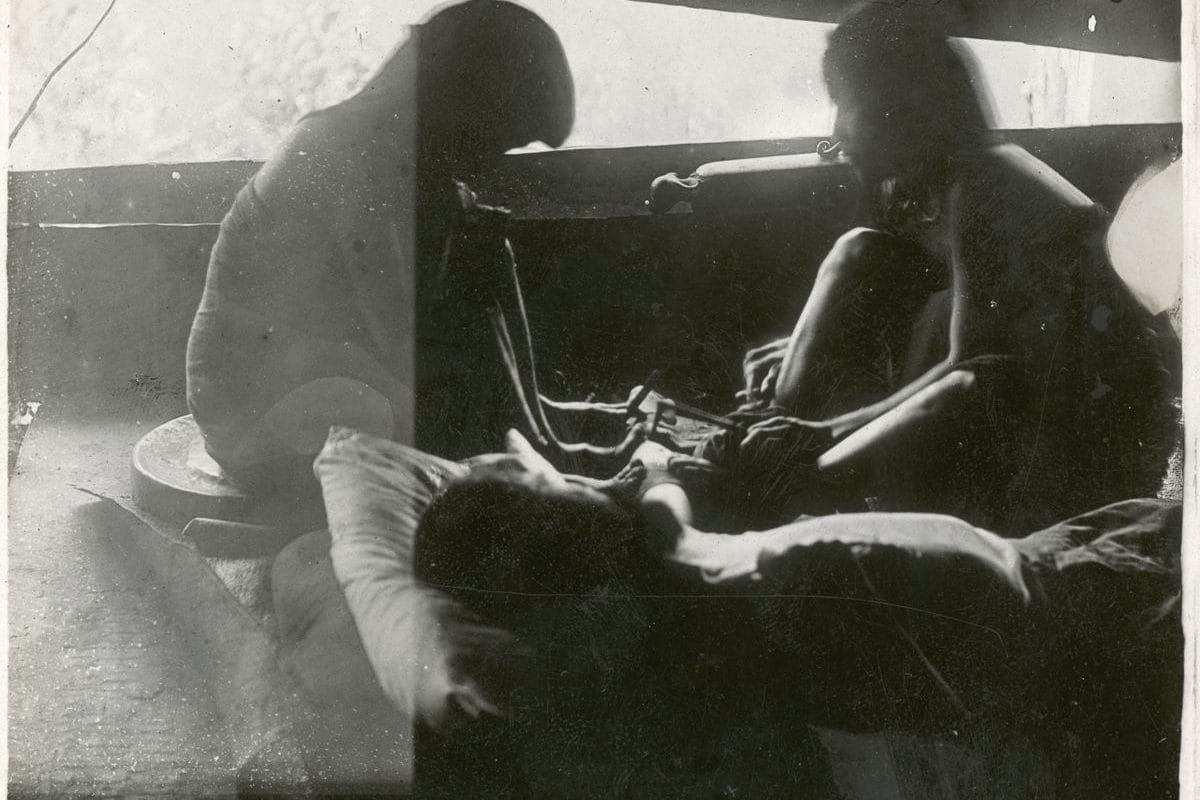

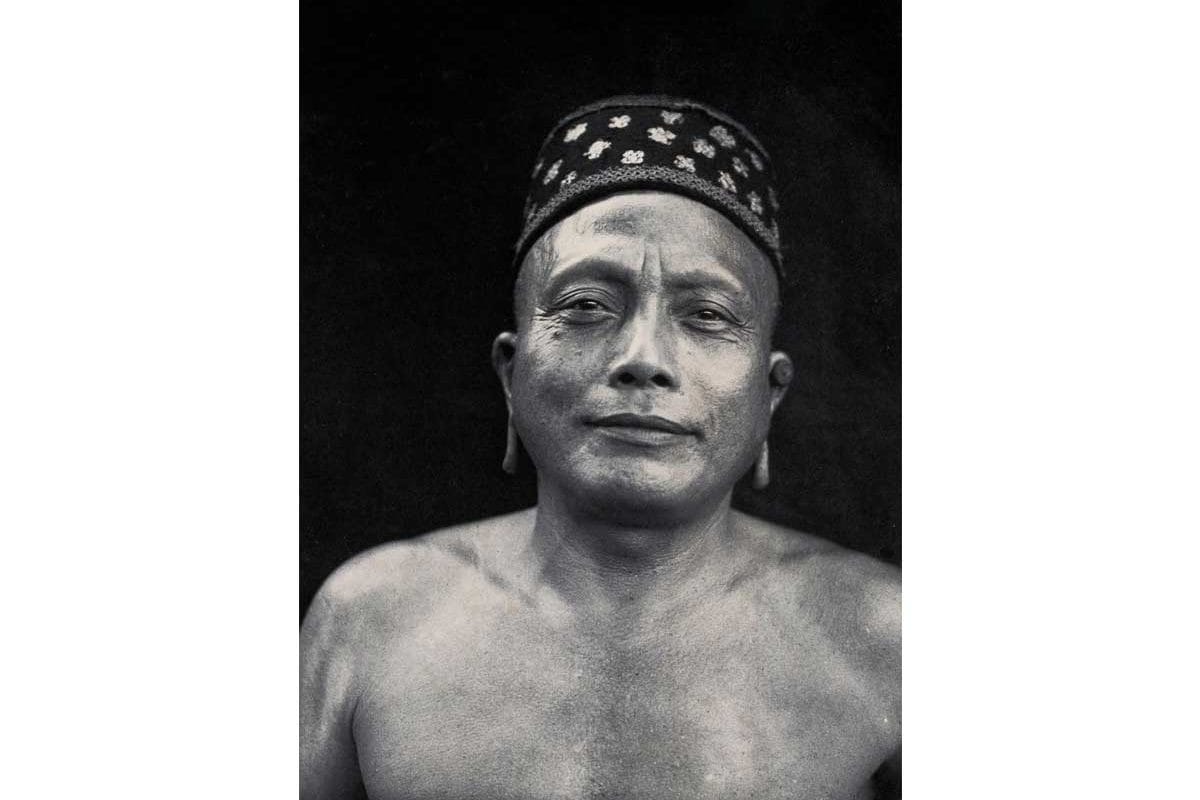

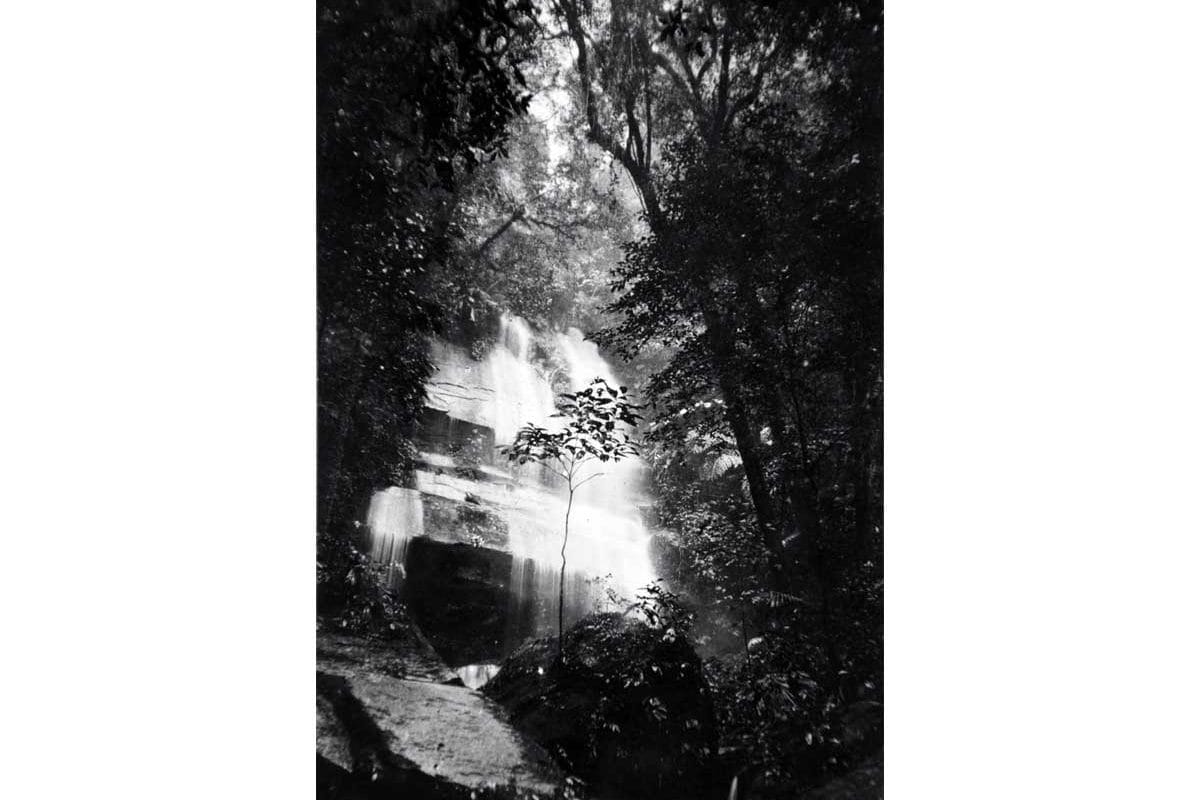

A tattoo is inked into skin. It is an intangible cultural practice that cannot be easily collected or displayed in a museum. Many of these photographs were taken by ethnographers and colonial officers in Borneo at the end of the 19th century. They were taken to document indigenous ways of life, which the photographers believed would soon disappear. However, the photographs might also tell another story.

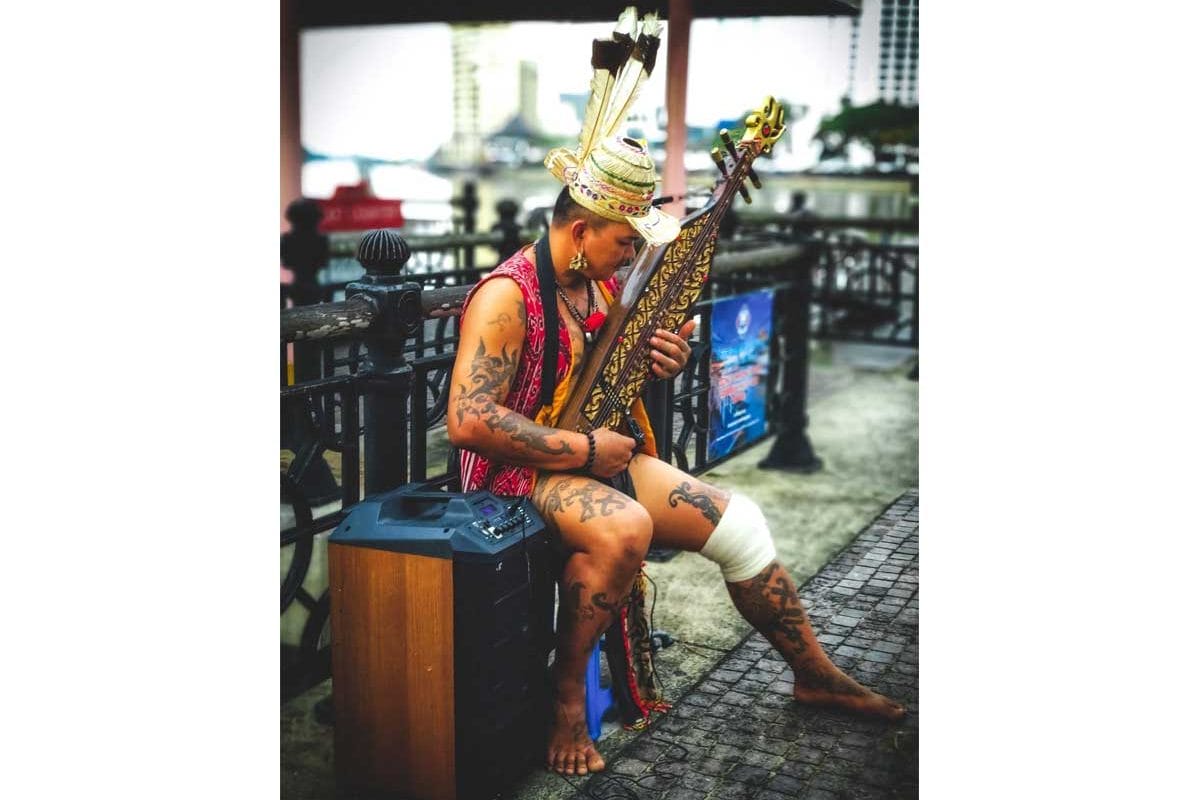

Many indigenous artists in Borneo perform hand-tapped tattooing. They use a wooden mallet, a steady hand and a needle dipped in ink. The Kayan, an indigenous tribe from Sarawak, historically used tattoos to celebrate victory in conflict, or to recognize achievements in weaving, singing and dancing. By marking their achievements in life, tattoos were thought to guide the Kayan after death.

The process of tattooing often took several years to complete. It was expensive and required knowledge of complex ritual. Kayan tattoos were always performed by women. It was these women who understood the rituals, and the significance of different designs and motifs. The skill and knowledge of tattooing would be passed from mother to daughter.

How do you collect these skills?

And how do you display this knowledge in a museum?

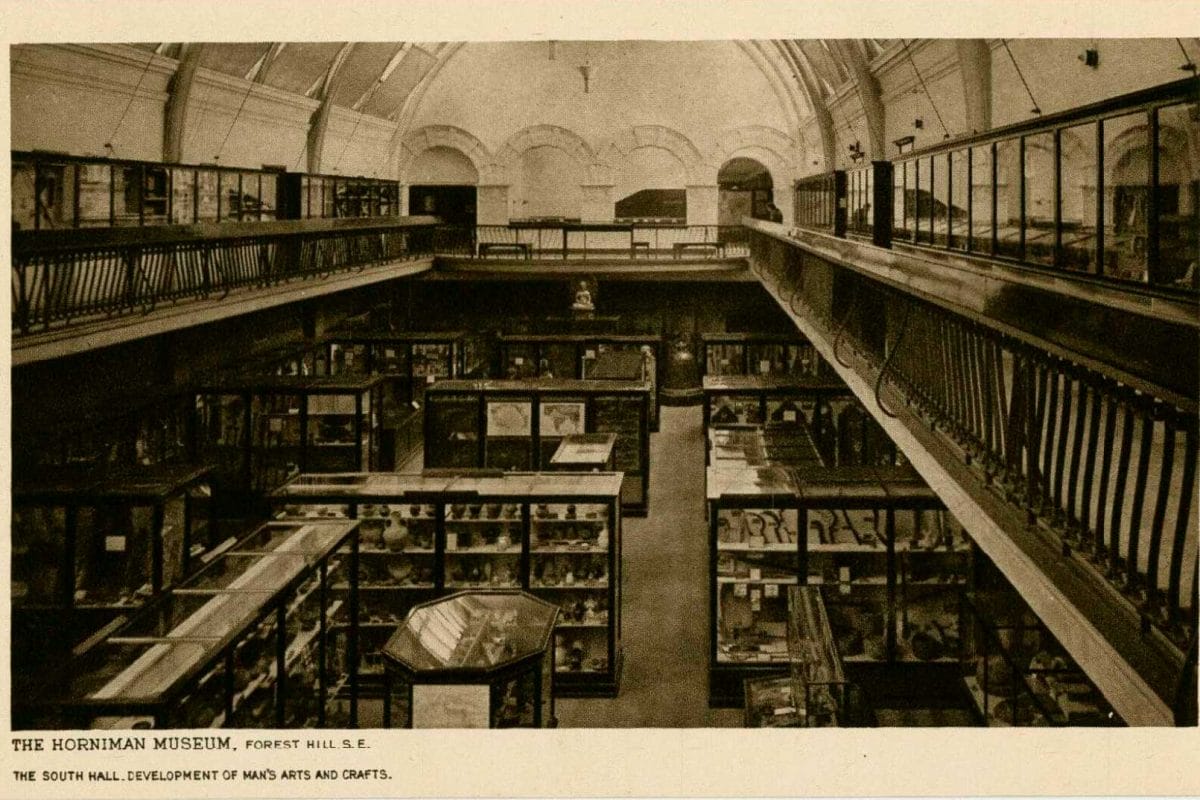

In the collections of the Horniman Museum and Gardens, there are wooden models, carved and painted with Kayan tattoo designs. The models might provide answers to these questions. But they also raise another:

Why would you collect a tattoo?

“We owe our knowledge of their tatu to an aged Klemantan, who was well acquainted with the tribe before their disappearance. At our behest he carved on some wooden models of arms and legs the tatu designs of these people..."

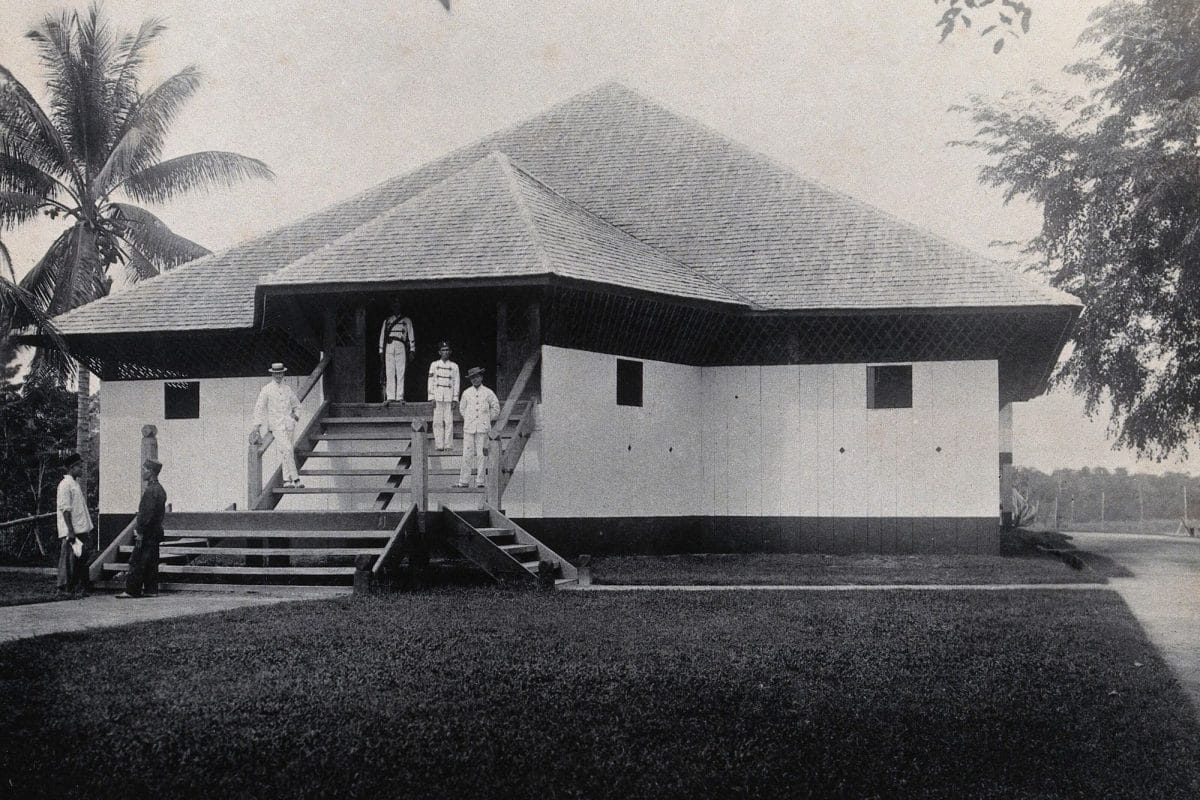

The colonial officer Charles Hose worked in Sarawak between 1884 and 1906. According to his book ‘The Pagan Tribes of Borneo’, Hose asked indigenous artists to carve tattoo designs on wooden models. It is unknown if the artists were paid fairly for their work. However, Hose now had representations of this skill and knowledge. These ‘artefacts’ were later shared with colleagues and acquaintances.

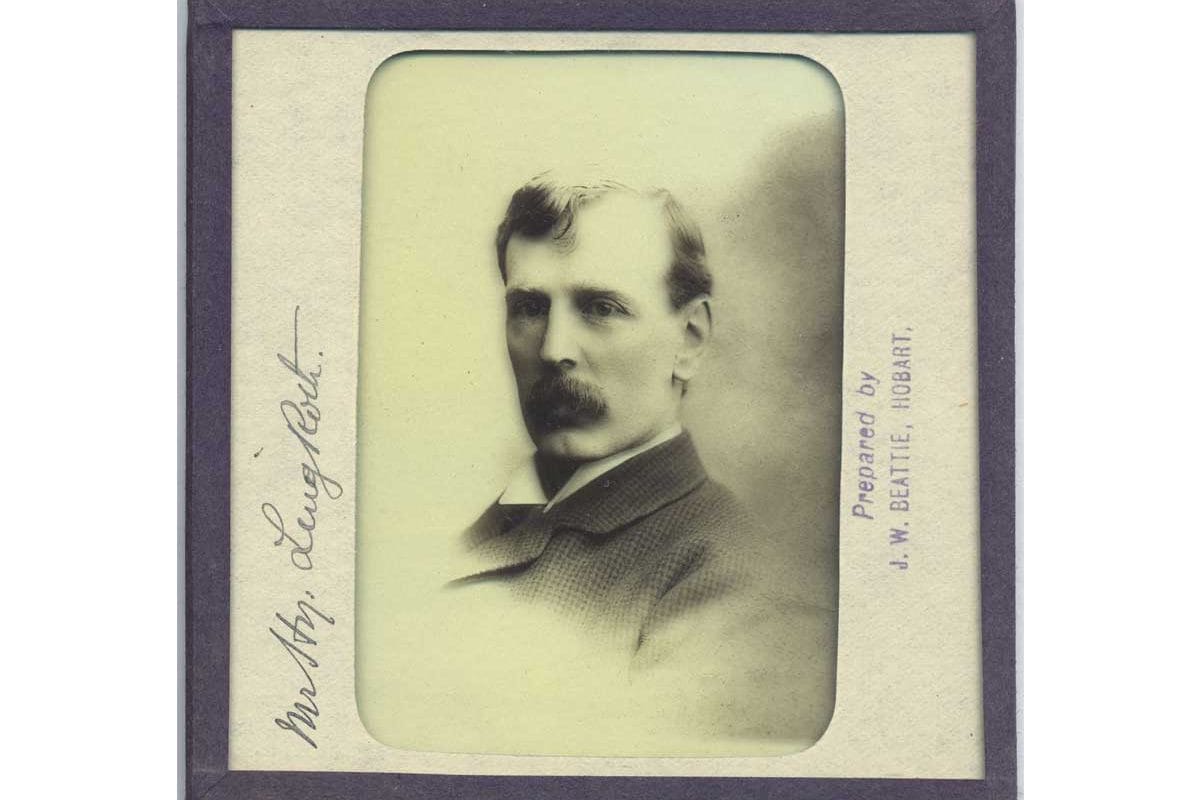

Hose’s colleague, Henry Ling Roth believed that all societies moved through three stages of development: from savagery, to barbarism, to civilization. He argued that to endure the pain of tattooing, indigenous peoples must be biologically different, – and racially inferior, – to the supposedly civilized people of the western world. In these racist and pseudo-scientific ideas, we find the roots of white supremacy.

In 1903 Ling Roth wrote:

"our governing officials should have a thorough knowledge of the native races subject to them – and this is the knowledge that anthropology can give them – for such knowledge can teach what methods of government and what forms of taxation are most suited to the particular tribes, or to the stage of civilisation in which we find them"

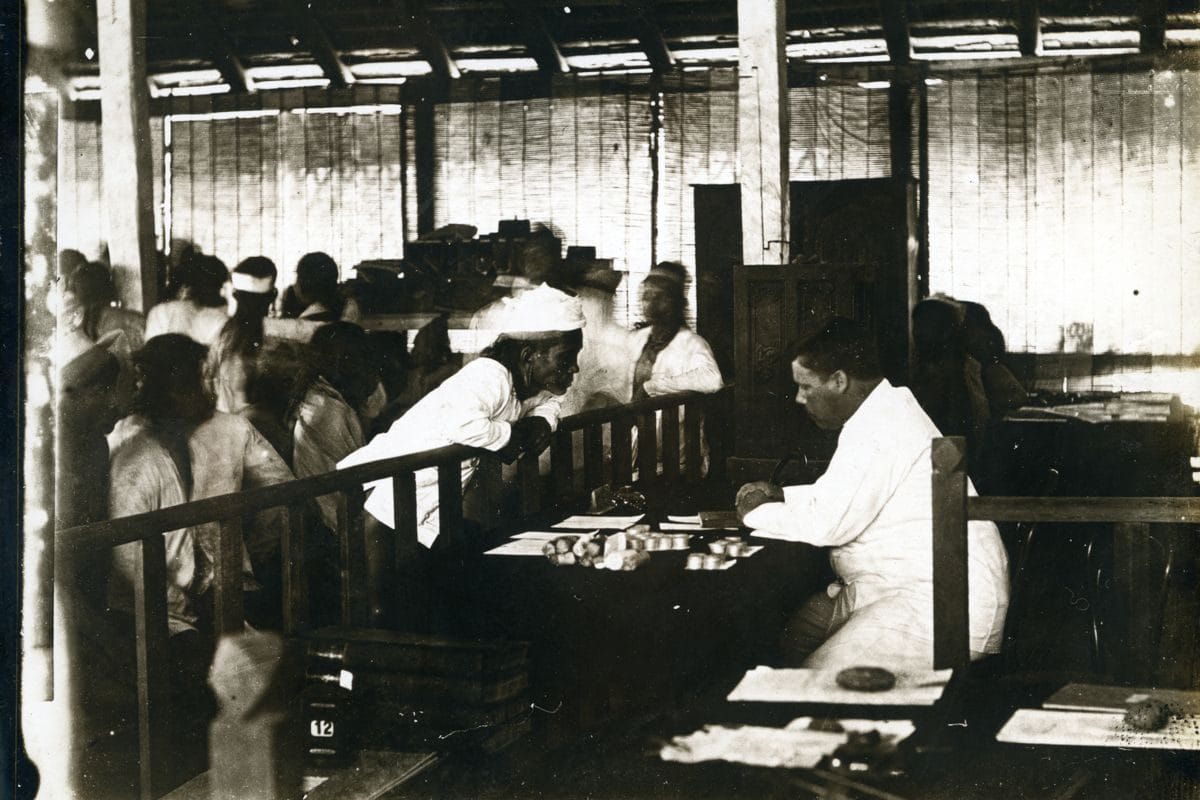

Here is a photo of Charles Hose. Can you see the coins stacked on the table?

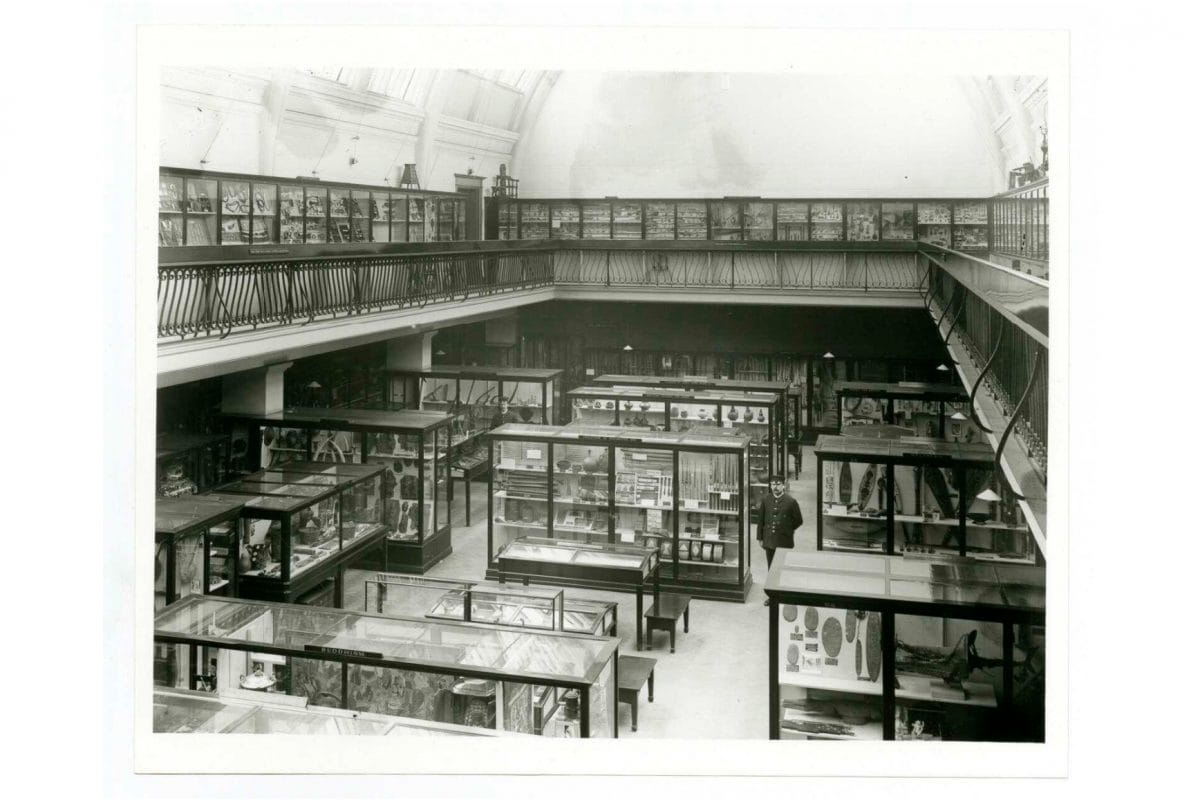

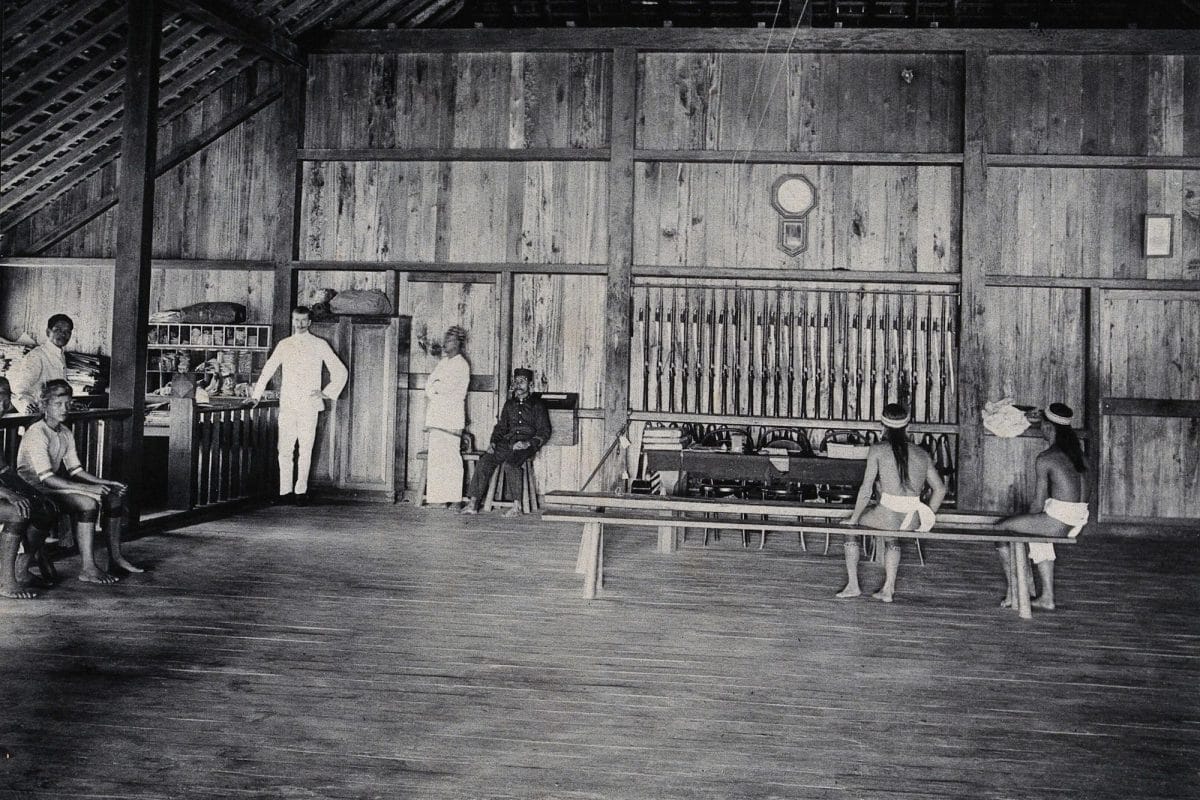

Hose was a governing official who benefitted from this anthropological knowledge. He had travelled along the Baram River and collected from the people he met. He found ways to preserve their material culture in glass cases. This information was then used to find which forms of taxation best suited the indigenous peoples of Borneo.

In 1899, Hose oversaw peace-making negotiations between indigenous tribes. He is remembered now for organising an annual boat race, intended as a peaceful way to settle tribal disputes. The Baram Regatta continues today, a vibrant festival of boats and beauty pageants, and a celebration of Sarawak’s multicultural identity. Despite this, some have argued that Hose’s legacy is more complicated.

It is believed that tribal leaders like Tama Bulan Wang had actually led the negotiations. Tama Bulan used his understanding of internal tribal politics to find alternative routes to peace. The contribution of colonial administrators and tax collectors, like Charles Hose, has likely been overstated. The true legacy of British and Dutch colonial rule can be found by looking elsewhere.

In 1910, Hose brokered deals with Shell Oil. The company then started drilling at the mouth of the Baram River. More than 100 years later, resources in Borneo are still exploited by fossil fuel industries. At the same time, extraordinary levels of deforestation have altered the social and environmental landscape of the island. With these rapid changes, indigenous ways of life have been constantly under threat.

Why would you collect a tattoo?

Throughout the 19th century, ethnographers and colonial officers travelled to Borneo. They met peoples with oral histories and deep memories. They had transmitted their ways of life for hundreds of years without interruption.

The ethnographers collected these ways of life, and then placed examples of material culture in distant museums. They remain in museums today, often located more than 7000 miles away from the communities who value them.

At the same time, the colonial officers used the collections to justify unfit methods of government and taxation. These methods were intended to end indigenous ways of life. The Kayan continue to live with the consequences.

Is there a different way to collect a tattoo?

Tattoo artists from different communities share designs. They adapt historic practices, as they search for new meanings that speak to life in Southeast Asia in the 21st century. Indigenous activists fight to keep their ancestral land and resources. Many also attempt to preserve traditional arts, like beadwork, music, and tattooing. Artists and activists explore together how these two challenges might be closely interconnected.

Meanwhile, Malaysian software developers CtrlD Studios have created an augmented reality game for smartphones and tablets. In the game, a young Kayan girl called Ano is about to receive her first tattoo. She must complete difficult challenges and learn, from her grandmother, the significance of tattoo designs and motifs.

Perhaps this is how to collect a tattoo.

Credits and image licenses

Charles Hose and A.C. Haddon’s photographic archives are divided across different museums:

Wellcome Library (WL)

MAA, University of Cambridge

Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (PRM)

Portrait of Henry Ling Roth has been included with permission from the University of Tasmania (UTAS).

All other images were either taken by the author, or they have been reproduced from the institution with a CC-BY 4.0 license.

References and further reading

Gorman, A., (2008). ‘The Primitive Body and Colonial Administration,’ in The Roth Family. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Roth, H. L., (1903). Great Benin: Its Customs, Arts & Horrors. Halifax, Eng.: F. King & Sons Ltd.

Weinlein, E., (2017). ‘Indigenous People, Development and Environmental Justice,’ EnviroLab Asia: Vol. 1(1).

Hose, C. & McDougall, W., (1912). The Pagan Tribes of Borneo. London: MacMillan & Co. Ltd.

Roth, H. L., (1896). The Natives of Sarawak & British North Borneo. London: Truslove & Hanson.

Mashman, V., (2020). ‘Peace-Making, Adat and Tama Bulan Wang,’ Journal of Borneo-Kalimantan. Vol 6(1).

Rahim, R., (2019). ‘A People’s Heritage Fading’, 7th International Seminar on Nusantara Heritage ISONH.

Pitts, V., (2003). In the Flesh: The Cultural Politics of Body Modification. New York: Palgrave.