Who was Philip Henry Gosse?

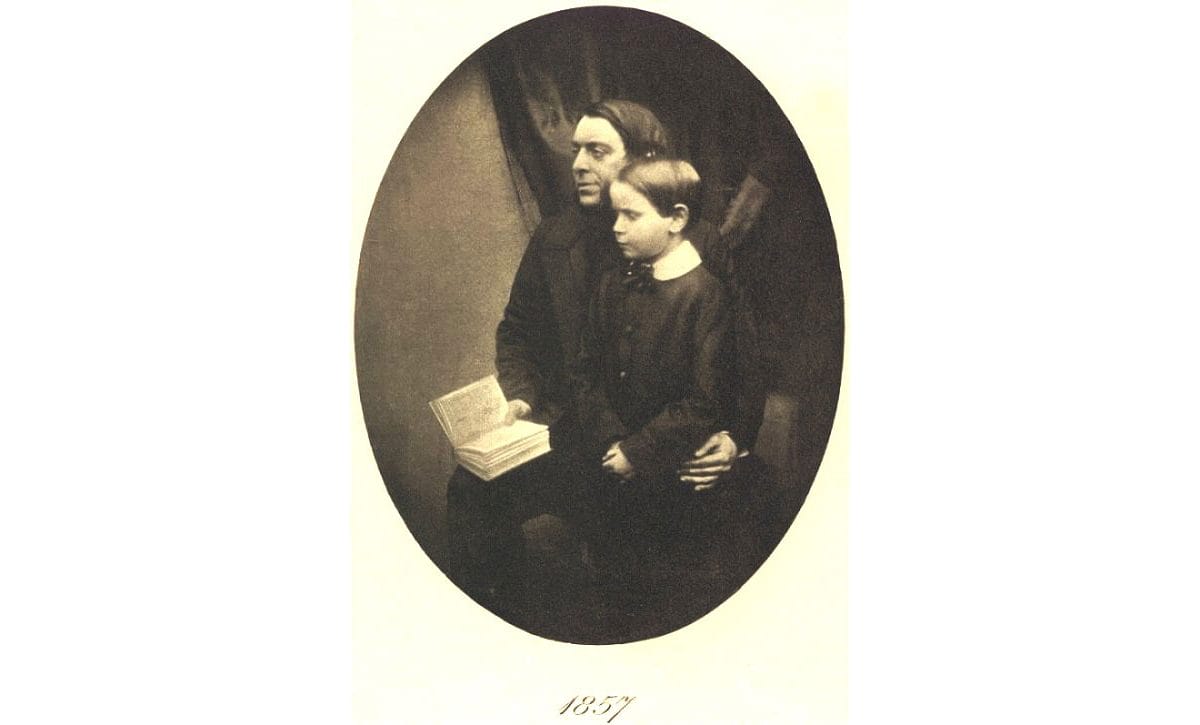

Phillip Henry Gosse was a self-taught field naturalist and zoologist. As a boy, he had been encouraged to watch and draw wildlife by his aunt, Susan Bell.

In his youth, he took scientific inspiration from his cousin Thomas Bell, a naturalist who later became a professor of zoology at King’s College, London.

As an adult, Gosse became a passionate collector and meticulous cataloguer of marine animals. His keen observations, practical flair, and extensive writing contributed to the development of Victorian zoology and even informed the insights of evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin (1809-1882).

Gosse’s specialist books include A Manual of Marine Zoology (1855-6) and Actinologia Britannica (1860), a student’s guide to British sea anemones and corals. We have a copy of Actinologia Britannica in our Library.

Gosse was a populariser too, writing and illustrating eight general books on coastal outings and marine life between 1844 and 1865. These books were read by some of the more leisured members of society now taking their holidays at the seaside courtesy of the new railways. Overall, Gosse had 39 books published in his lifetime.

Today, Gosse is remembered as a pioneer of the glazed marine aquarium who, in fact, coined this term. Following his experiments, glass boxes filled with salt water, plants, and animals became vital pieces of scientific apparatus. At the same time, a crystal clear aquarium tank also became a ‘must have’ display case of sea creatures for the fashionable Victorian conservatory.

Naturalist, scientist… and creationist?

Gosse’s early career took him across the Atlantic to Canada, the USA, and Jamaica where he developed his skills as a naturalist while teaching. In each country, he tirelessly studied insects, birds, and plants out in the field.

By the 1840s, Gosse was back in Britain where he began collecting marine specimens in earnest. He did this both by coastal dredging from a boat and by exploring the geologically varied shores of Dorset and Devon on foot where eroding tides had created many sheltered habitats for diverse, intertidal life.

When back indoors, Gosse would assume the role of a scientist looking carefully and dispassionately at his latest catches. In his study, he would compile notes – often with the aid of a microscope – and record his specimens following the two-part naming system of Carl Linnaeus (1707-78). Whenever Gosse observed “prominent varieties of each species” he would devise his own informal names for them (Gosse, 1860 p.vii). His sensitivity to geographical variation in species ran parallel to Darwin’s, but their broader thoughts on evolution would always remain distinct.

Gosse combined a love of observing with collecting, careful study, drawing, and writing. Although Gosse’s creationist theories finally marginalised him, his taxonomic work and practical contributions to marine zoology proved important for the scientific establishment of his day, and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1856.

At the centre of Gosse’s life and work stood his strong Christian beliefs. Originally a Methodist, he joined a small, non-conformist group called the Brethren in the 1840s.

To Gosse’s mind, the ordered beauty of a rock pool at low tide revealed the handiwork of a divine creator. For him, it could also mirror a lost Eden, or symbolise the harmonious world yet to come. According to Gosse, animals and plants were divinely ordained, ‘fixed kinds’ of species that had only diversified over millennia because of God’s benign will. Gosse’s chosen role was to witness, catalogue, and celebrate this blessed variety of life.

Gosse was not the only zoologist at this period trying to reconcile Scripture with fossil finds and new evolutionary theory. However, his devout brand of ‘natural theology’ was especially tested following the publication of Darwin’s On The Origin of Species in 1859.

In his book Omphalos: An Attempt to Untie the Geological Knot (1857), Gosse argued that fossils had been placed on Earth by God, so that the world would appear older than it is. Falling from favour, Gosse chose to withdraw from public life and return to the South Devon coast. Darwin, however, continued to value Gosse’s sharp-eyed fieldwork and later corresponded with him on birds and orchid reproduction.

The sea is HIS, and He made it

Studying under the waves

It was easy for Gosse to watch and share with others the “perpetual novelty” of life on land (Gosse, 1840 p.226). However, life underwater was far less visible – to him or anyone else – and its revelation proved a tough test for the enthusiastic naturalist.

Diving technology and photography were in their infancy so Gosse had little choice other than to bring his seaside subjects up to the surface.

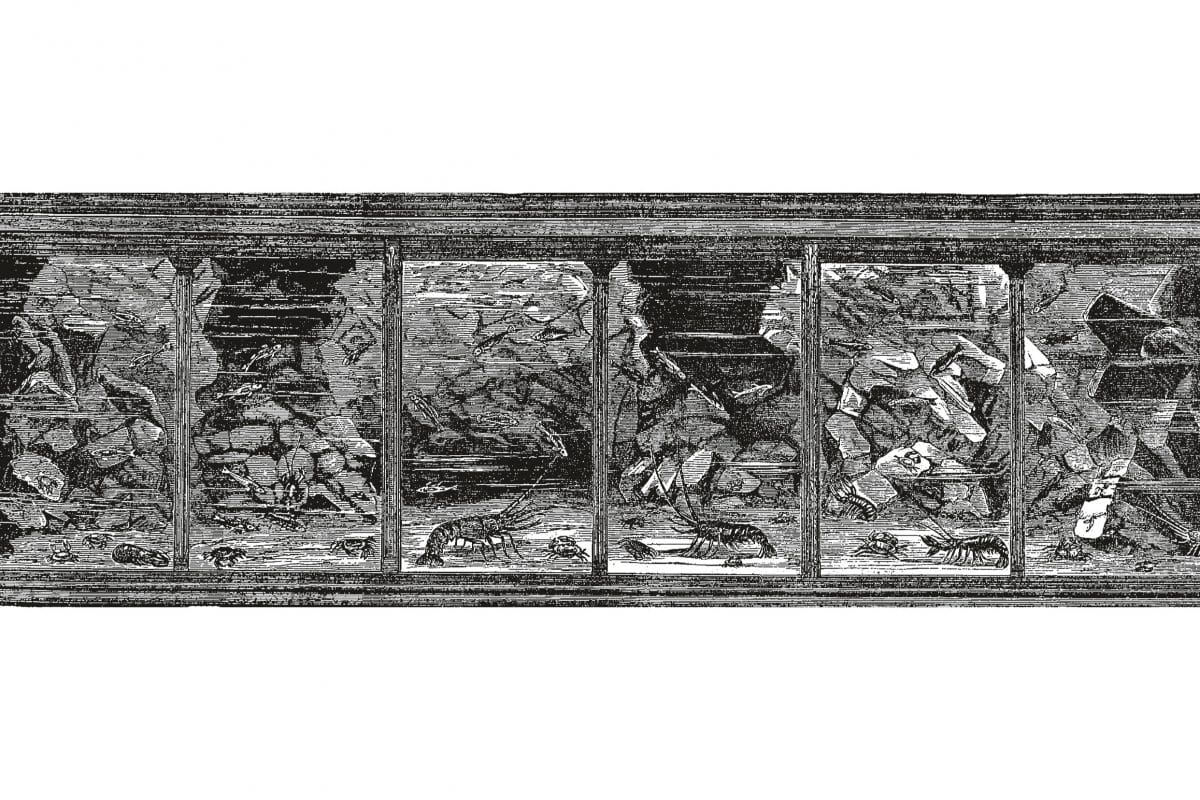

He netted his specimens at low tide placing them carefully in baskets and jars. Gosse then quickly went home and poured everything into a wood-framed tank of plate-glass sides and slate bottom placed at his “study table”. He then began watching and sketching. With this transparent box, Gosse had successfully fabricated an easy-to-study “portion of the sea” (Gosse, 1865 pp.62-3).

Careful husbandry of the artificial community was to be crucial for keeping these “interesting collections of aquatic animals alive” (Gosse, 1865 p.251). Through trial and error, Gosse discovered how to stock and maintain a biologically balanced saltwater tank.

He also learned to include rocks for hideaways, introduce suitable seaweeds and aerate the whole with a water circulation system.

What was special about his observations?

Gosse dismissed many existing books on marine life. In his opinion, their vague textual descriptions made them poor identification guides. Wanting something better, Gosse wrote that he was “compelled… to draw up the characteristics of my subject” from scratch, adding:

I have resorted to nature itself; I have studied the living animals

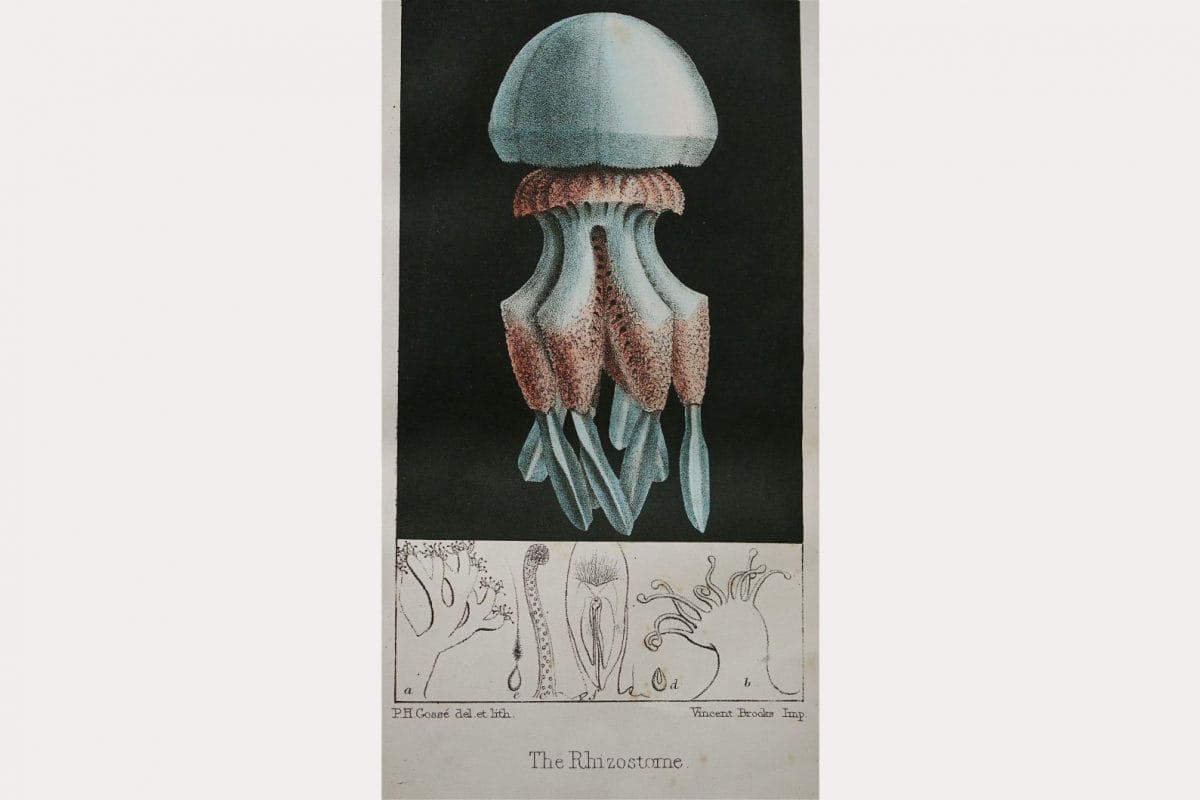

Gosse knew that reliable records of the shapes, colours, and behaviour of living specimens were crucial for both scientific progress and popular impact. Such accurate recording depended on two things: keeping his animals in rude health and having a clear, undistorted view of them.

With a healthy community and a glazed tank, Gosse could write precisely about his subjects and depict them with faithful detail.

To preserve the tints and tones of his original watercolour studies, Gosse oversaw the making of the printer’s chromolithographic plates. The resulting hues in Gosse’s groundbreaking book illustrations remain vivid evocations of the shore and deep seas species he observed even today.

Some of his paintings and preparatory collages survive and are now kept in the library of the Horniman Museum and Gardens.

Did he invent the marine aquarium?

Gosse cannot take sole credit for inventing the marine aquarium, others took part in the conception and development of the viable saltwater aquarium. However, it was he who most effectively promoted the glass tank as a novel ‘theatre’ for sea creatures, perfected tank care. and gave the glass vessel the name we still use today.

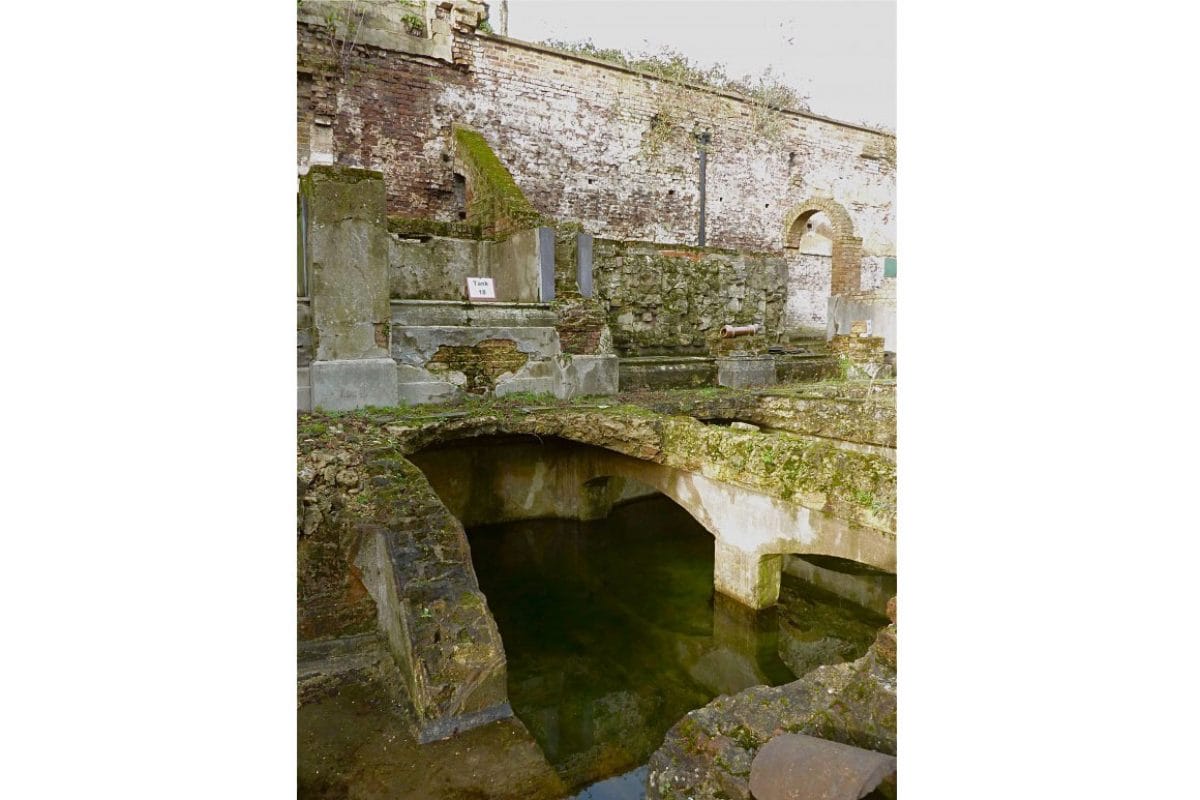

Gosse successfully brought the realities and pleasures of keeping a see-through tank to the attention of scientists and aquarium curators. His dedication saw him become an associate of those responsible for the ‘Fish House’ in Regent’s Park Zoological Gardens (1853) and helped to furnish its marine tanks with algae and animals he had collected.

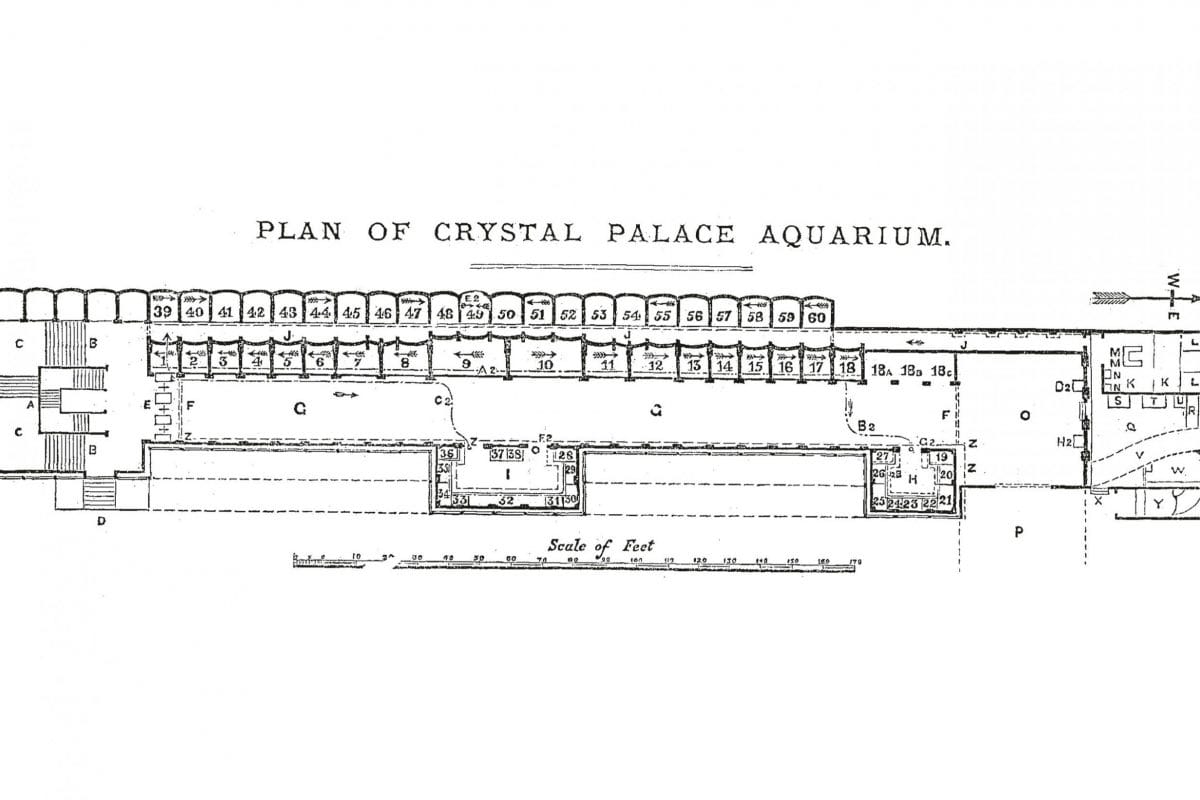

Gosse would have shared ideas and his enthusiasm with close friend and aquarium retailer William Alford Lloyd who became superintendent of the Crystal Palace Aquarium in the 1870s (Parlour Aquariums, 2014). Even Darwin turned to Gosse when setting-up an aquarium of his own and chose to follow the Gosse formula for making artificial seawater.

Gosse also happily shared his knowledge with a mass audience of seaside naturalists in A Handbook to the Marine Aquarium (1856). In its pages he offered practical advice, stressing the need for vigilance and biochemical know-how.

Gosse the populariser rejected the awkward term of ‘aqua-vivarium’ and instead chose to call this functional, appealing device the ‘aquarium’, declaring the word to be “neat, easily pronounced and easily remembered” (Gosse, 1856 p.250).

How is Gosse remembered?

Gosse transformed his raw passion for nature into scientific records, books, and pioneer aquarium husbandry. He devised an aquarium “made wholly of plate-glass”, allowing “distinct vision in every part” (Gosse, writing in 1853 and quoted by Stiles, 2009).

More importantly, Gosse successfully managed the ‘ecology’ of that transparent saltwater aquarium. Wild specimens of shrimp, hermit crab, gobies, and sea anemones now remained alive. The biological diversity of British shores could be accurately recorded and enjoyed for the first time.

By the end of the century, Gosse’s work on marine animal morphology (shape) had been overtaken by studies of anatomy (internal structure). To acknowledge Gosse’s pioneering contributions, some of his paintings were given to the Horniman Museum and Library in 1906 by Advisory Curator and fellow sea anemone expert Alfred Cort Haddon FRS (1855-1940).

Gosse’s achievements as a zoologist and populariser are celebrated in the first display of the Horniman Aquarium. Here, visitors can, like Gosse, distinguish one species of sea anemone from another.

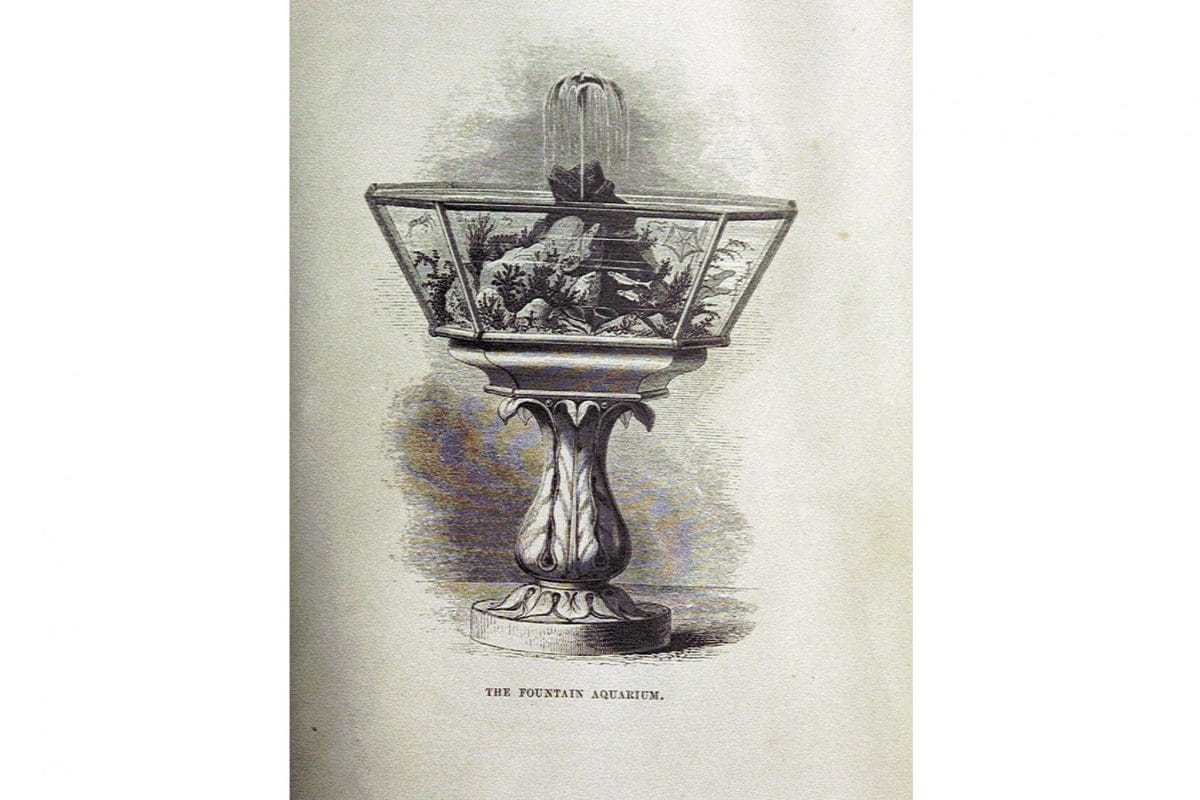

The aquarium’s Gosse-inspired fountain tank, on the other hand, invites everyone to delight in spotting its small camouflaged fish and transparent shrimp – just as Victorian families would have done at home with their aquariums more than a century and a half ago.

Sources

- Gosse, P.H., 1840. The Canadian Naturalist. A series of conversations on the natural history of Lower Canada. London: John Van Voorst.

- Gosse, P.H., 1854. The Aquarium: an unveiling of the wonders of the deep sea. London: John Van Voorst.

- Gosse, P.H., 1855-6. A Manual of Marine Zoology for the British Isles, Parts I & 2. London: John Van Voorst.

- Gosse, P.H., 1856. Tenby: A Sea-side holiday. London: John Van Vorst.

- Gosse, P.H., 1860. Actinologia Britannica: A history of the British sea-anemones and corals with coloured figures of the species and principal varieties. London: Van Voorst.

- Gosse, P.H., 1865. A Year at the Shore. London: Alexander Strahan.

- Parlour Aquariums, 2014. [Accessed 2 April 2014].

- Stiles, P., 2009. Darwin & Philip Henry Gosse. [Accessed 19 December 2013].

- The Ocean [1844]. Philadelphia: Parry and McMillan 1859.

- Natural History: Fishes. London: Society for Promoting Christian

Knowledge, 1851. - A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast. London: John Van

Voorst, 1853. - Seaside Pleasures: Sketches in the Neighbourhood of Ilfracombe. Written

with his wife Emily and published anonymously, 1853. - A Handbook to the Marine Aquarium Containing Instructions for

Constructing, stocking and Maintaining a Tank, and for Collecting Plants

and Animals. London John Van Voorst, 1855. - The Aquarium: An unveiling of the wonders of the deep sea. 2nd ed.

revised and enlarged. London: John Van Voorst, 1856. - Brunner, B., The Ocean at Home: An Illustrated History of the Aquarium.

London: Reaktion Books, 2011. - Croft, L.R., ‘Gosse, Philip Henry (1810–1888)’, Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. [Accessed 13 December

2013] - Davies, J., ‘Western Channel (Durlston Head to Cape Cornwall, including

the Isles of Scilly) MNCR Sector 8’, Marine Nature Conservation Review.

Benthic ecosystems of Great Britain and the north-east Atlantic, ed. by K.

Hiscock, 1998, 219-253. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation

Committee (Coasts and Seas of the United Kingdom, MNCR series). - Smith, J., ‘Eden Under Water: The Visual Natural Theology of Philip Henry

Gosse’s Aquarium Books’, A talk presented at ‘Nineteenth-Century

Religion and the Fragmentation of Culture in Europe and America’

Lancaster, England, July 1997. [Accessed 19 December 2013]. - Smith, J., Charles Darwin and Victorian Visual Culture. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2006. - Thwaite, A., Glimpses of the Wonderful: The life of Philip Henry Gosse

(1810-1888). London: Faber & Faber 2002.