Legend has it that the Surrey House Museum, the predecessor to the Horniman, was put in motion by something that has become all too familiar during lockdown, a lack of space and a domestic spat.

The story goes that by 1888, nearly 30 years after Frederick Horniman started collecting artefacts and natural history specimens, his wife Rebekah had grown increasingly frustrated with the shrinking space in their family home. Rebekah gave her husband an ultimatum, “either the collection goes or we do”. Frederick agreed, later stating in an article for Pearsons Weekly,

My family and I were literally crowded out by the many objects that I was continually adding to my collection

Thus, the Horniman family moved to Surrey Mount in 1889 and the Surrey House Museum opened the following year on Christmas Eve.

But is this origin story quite so simple? Could there have been other circumstances leading to the opening of the Surrey House Museum?

My PhD research, which looks at the Museum’s connections to empire, suggests other motives were in play. These include the promotion of Horniman’s successful tea trade and his desire for social reform. My research also places the opening of the Museum within wider imperial trends, suggesting that the story of the Surrey House Museum is inseparable from the story of empire.

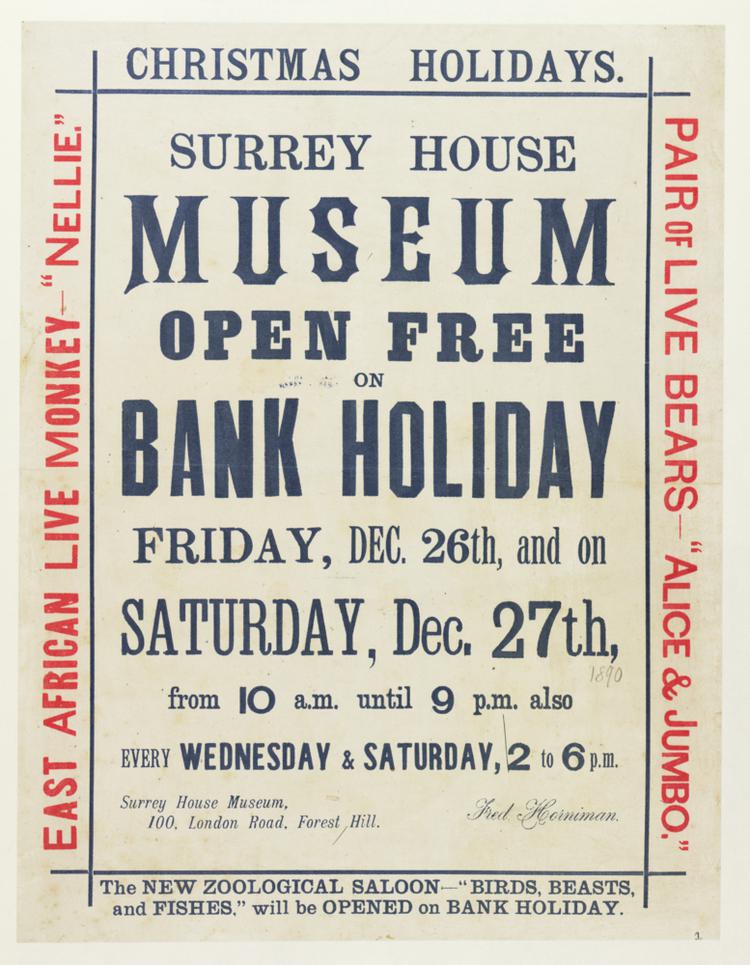

Surrey House Museum poster, 1890

Archive

To understand the origin of the Surrey House Museum we must first follow the money.

Frederick Horniman made his money from Horniman’s Tea, the import business he inherited from his father. The wealth derived from Horniman’s Tea allowed him to travel and collect before opening the Surrey House Museum to showcase his collections. Research into Horniman’s Tea and its links to empire is ongoing.

What we do know is that tea played an important role in the Opium Wars in China, where Horniman’s Tea sourced most of its product. More generally, the late Victorian tea industry was responsible for the exploitation of cheap labour and the appropriation of land for plantations in places where tea is grown, like Assam in India. The Surrey House Museum was just one beneficiary of this booming Victorian tea industry.

Yet, links between Britain’s favourite hot drink, imperialism and the Horniman extend beyond financial gain. While Horniman was importing Chinese tea to meet consumer demand in Britain, he was also helping to quench a thirst for knowledge of world cultures with artefacts from Asia.

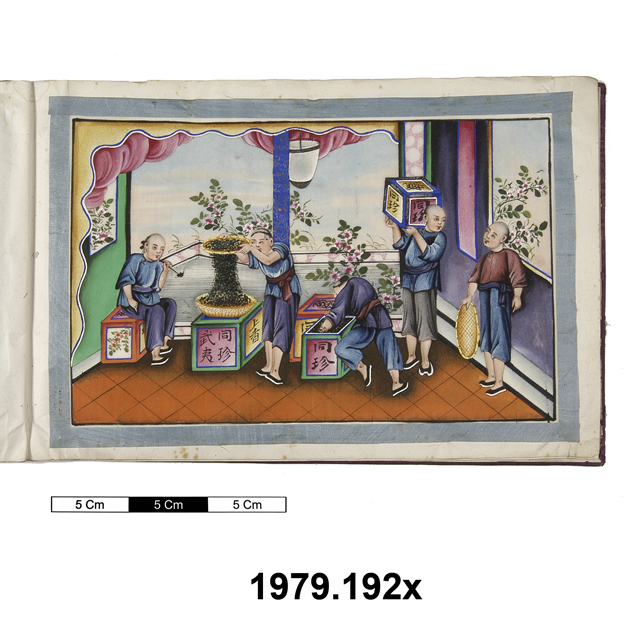

The 1890 guidebook to the Surrey House Museum notes that on a large table in the centre of what was called the African and Japanese Room were three albums of “Chinese paintings on so-called rice paper”. These albums represented the various stages of life in China from birth to death, different trades and occupations, and “processes of Tea culture, from preparing the ground to exporting the Tea”.

Like the tea leaves they depicted, these albums were brought to Britain on a Chinese tea clipper, named ‘Omba’, in the possession of Captain Geo F. Thomson. As such, they tell a small part of Britain’s imperial history, in which Britain’s global strength relied on the extraction of resources from other countries. These resources came in the form of raw materials, labour or cultural artefacts.

The Chinese albums, therefore, highlight the link between the extraction of commodities and artefacts under British imperialism.

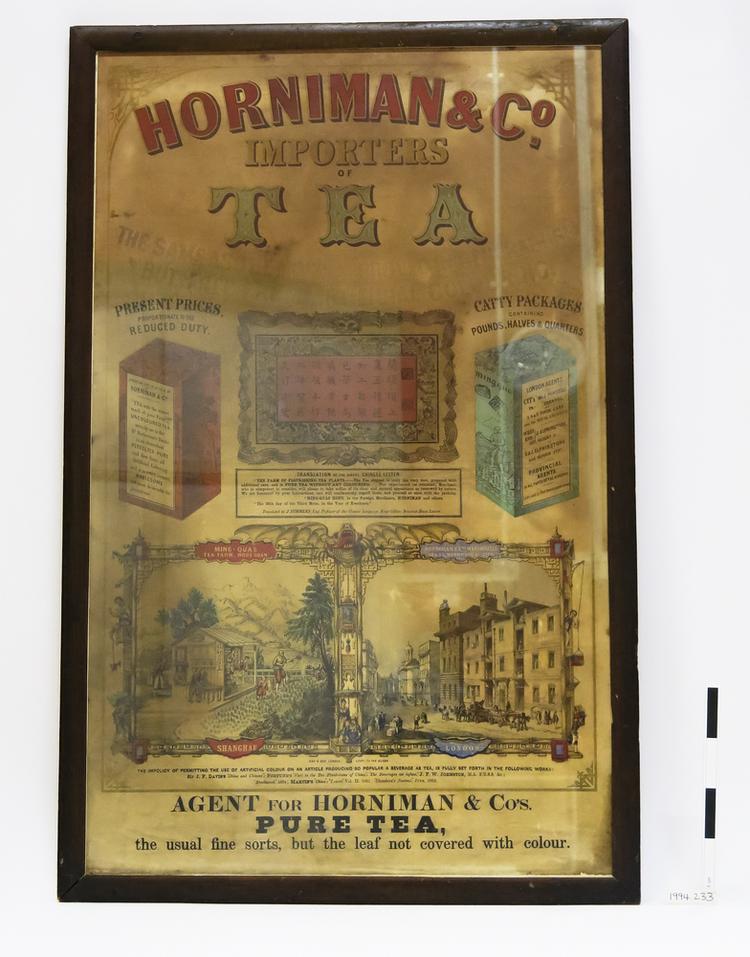

The Surrey House Museum also offered Frederick Horniman an opportunity to promote his tea business.

Advertising for Horniman’s Tea and other import businesses frequently used images of non-Western workers producing goods for Western consumption similar to those in the Chinese albums. Similarly, the Indian Tea Syndicate regularly sponsored exhibitions and tea rooms to simultaneously promote an interest in Indian culture and commodities.

The importation of consumer goods and material culture from the global South were closely intertwined.

poster

Anthropology

painting (art)

Anthropology

Frederick Horniman’s interest in social reform may have provided another motivation for founding the Surrey House Museum. Horniman was elected as a Liberal MP in 1895 and campaigned throughout his life to improve the living conditions of the working class.

Opening the Surrey House Museum, and later the Horniman Museum and Gardens, as a free, public institution was seen by many as a natural extension of his social philanthropy. An 1891 newspaper article even profiled Horniman in their ‘Gallery of Munificencies’, praising him for “handing over to the public the treasures of his museum” and presenting him as an example for other wealthy men.

You can view the article in more detail by viewing it in the Collections online, and clicking on the magnifying glass.

The Surrey House Museum could also be seen as part of a broader tradition of social reform of the urban poor.

Historians have noted that, as museums exploded in number in late nineteenth century, social reformers hoped to lure the urban poor away from public houses with the promotion of museum excursions as a respectable leisure activity. Museums even issued manuals instructing working-class visitors on what to wear and how to behave appropriately in museum spaces.

However, the use of museums as a tool for social reform didn’t only impact class identities but also racial identities. The Surrey House Museum, and many others like it, presented non-Western cultures as inferior to European cultures. This was in keeping with a British imperialist ideology that placed different races and cultures in an imagined social hierarchy.

Museum-goers of all classes were encouraged to see themselves in this way also, as members of a superior race with a role to play in empire. This is often referred to as ‘social imperialism’ and it is important for understanding not only the impact of imperialism on colonised territories but on the formation of a British national identity.

We may never know Frederick Horniman’s exact motivations for opening the Surrey House Museum on Christmas Eve in 1890.

Most likely they were multiple and intersecting. What is clear is that the Surrey House Museum, and later the Horniman, are just small parts of a wider imperial history. My PhD research aims to better situate them within this history. Over the next few years, I will investigate the unknown legacies of imperialism within Horniman’s founding collections, and question to what extent did the Horniman uphold and justify colonial violence. I am particularly interested in how its display of material cultures from the empire shaped understandings of imperialism and identity back home in Britain.

The Horniman has undergone a number of changes since 1890. Not only have Frederick Horniman’s original collections moved from his family home to Surrey Mount, to the current museum site, but successive generations have re-interpreted and re-evaluated them.

Yet, beneath the surface, Frederick Horniman’s vision, his complex links to empire and the legacy of the Surrey House Museum remain.

This project is generously funded by AHRC and Midlands4Cities.