Cat. With. Spots

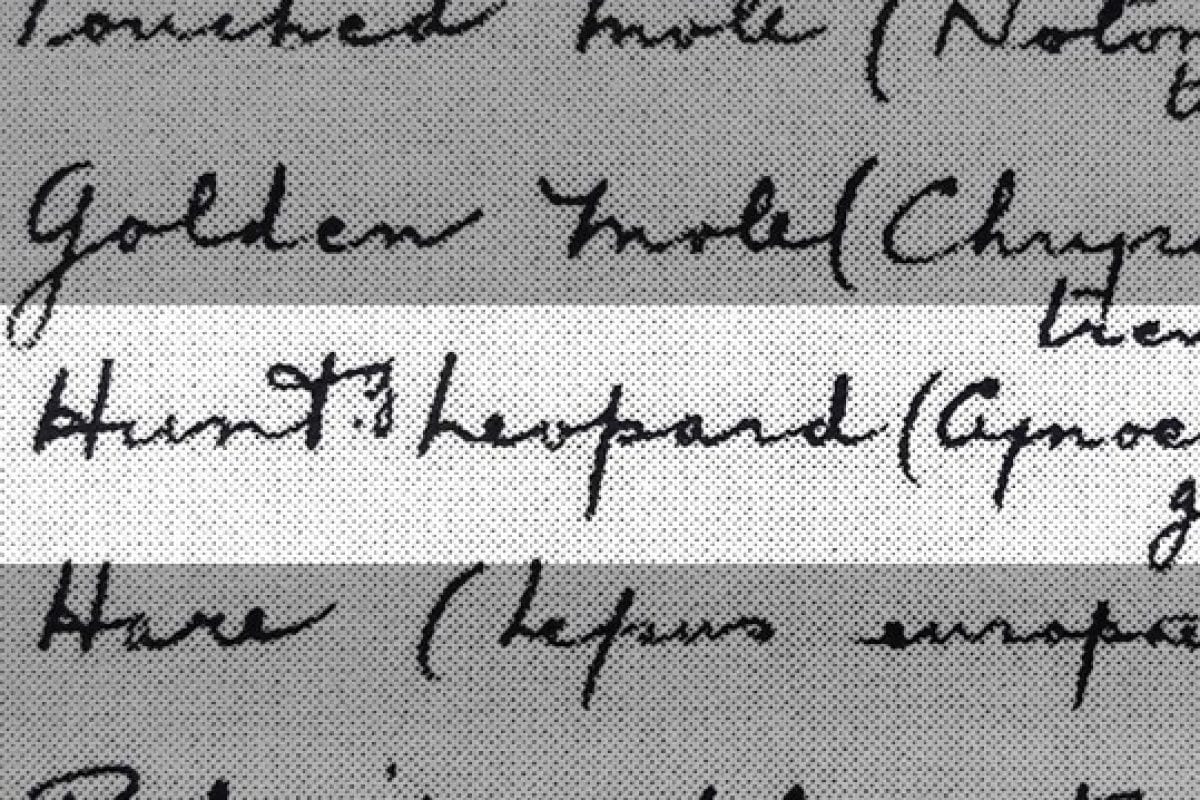

The image below is of the Horniman’s Accession Register in 1910, when the cheetah was first acquired by the Museum. It reads ‘Hunt.g leopard’. I have a Ph.D. in sharks; I am definitely qualified to say that what we have is a cheetah, not a leopard. Wondering whether it could have been a mistake, I started digging into the original taxonomy and common names of the cheetah and discovered something interesting…

Back during the height of the British Colonial era, and India was temporarily renamed British India, cheetahs were kept in captivity as feline ‘hunting dogs’ by the upper-class members of Indian society. The hunting part of the name ‘hunting leopard’ makes sense but as Asia also has leopards why they mixed the common names is anyone’s invitation to research.

As our cheetah arrived at the Horniman in 1910, when India was yet to kick the British out, I suppose it is reasonable that the specimen was recorded as ‘hunting leopard’ rather than ‘cheetah’, however confusing that was going to be for future Deputy Keepers of Natural History. Tsk.

So Many Cheetahs, and So Few

Scientists have proposed that the cheetah is split into five different subspecies. However, genetic analyses haven’t yet been used to confirm, or deny, their differences. One fairly confident split is between the Asiatic/Iranian cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus venaticus), and the African cheetah, which encompasses all four remaining, potential, subspecies:

- Northwest African cheetah (A. j. hecki)

- East African cheetah (A. j. fearsoni)

- Southern African cheetah (A. j. jubatus)

- Northeast African cheetah (A. j. soemmerringi)

Although the Asiatic and African cheetahs have had around 100,000 years to change their appearance and try something new, the two cheetah types still look pretty much identical (see the picture below). Pretty lazy for the fastest land mammal in the world.

Just because I know you’re wondering, our specimen hails from South Africa. So until a rigorous genetic test is put in place, which subspecies it is will be anyone’s guess.

Deadly in Life After Death

Cheetahs are excellent predators and so it seems fitting then that even in death, our cheetah could still cause serious harm.

A few years ago our cheetah specimen was tested for harmful chemicals and traces of arsenic were found on the fur. The taxidermist who prepared the skin (pre-1910, which is when we acquired it) would have used arsenical soap to protect the specimen from pest damage.

Arsenic was a common pesticide used in taxidermy from the 1800s up until quite recently when Health and Safety departments became more health and safety conscious, and started testing things more rigorously. Our cheetah poses no threat whatsoever to the public in the gallery, but curators have to wear PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) when handling historic specimens.

Main image: Alexander Leisser.