Why the greater horseshoe?

You often hear people talk of the Latin name for an animal to refer to the Genus and Species, such as Homo sapien for a human. However, many of these scientific names actually stem from Greek.

The scientific name for the genus of the greater horseshoe bat is ‘Rhinolophus’. ‘Rhino’ comes from Greek, and means nose. ‘Lophus’ is also Greek, and means crest.

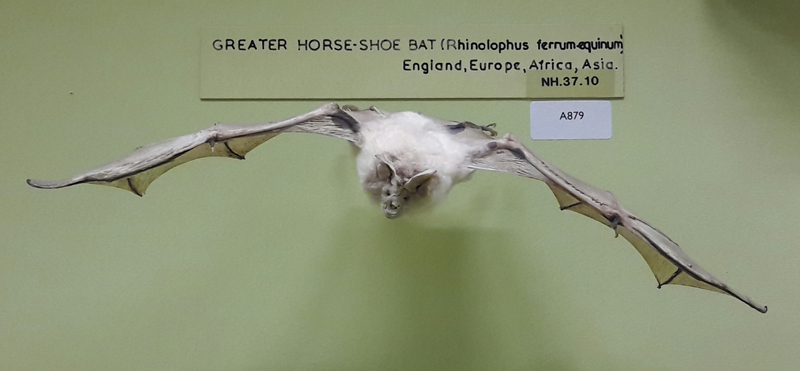

If you take a look at the greater horseshoe bat in the image below, you’ll see the logic behind a scientific name that means ‘nose crest’.

Another example is the rhinoceros, which happens to be both the common name and the scientific name for the Genus. The name rhinoceros stems from Greek and means ‘nose horn’. It’s all very logical.

Our Greater horseshoe bat came into the Museum in 1937 and is on display in the Natural History Gallery.

When referring to the Genus and Species of an animal, the correct term is the ‘binomial name’, which is Latin (not Greek) for ‘two names’. This worked perfectly until we realised evolution had ruined everything by proliferating beyond Genus and Species, at which point we had to introduce a third name for these; ‘Subspecies’.

When referring to a subspecies, the correct term is trinomial, which is Latin for ‘three names’. Subspecies tend to occur when two populations of the same species are separated for a significant period of time by some geographical boundary, and subsequently evolve different traits, yet remain so closely related that they’re still considered to be the same species.

The greater horseshoe bat has several subspecies (currently thought to be six), only one of which occurs in the UK; Rhinolophus ferrumequinum ferrumequinum.

Scientists, such as myself, are very fond of such semantics. However, I’m sure not everyone reading this will be so… let’s move on.

Can bats see in the dark?

Technically yes they can, but sight isn’t the sense they use to do this.

Whilst the binomial name for the greater horseshoe bat is very nice, the bat cares way more about its stomach, for which the nose crest comes in again.

As with all Microchiropterans (Microbats), the greater horseshoe bat uses echolocation to find dinner.

Echolocation is a system that does exactly what is says on the tin. A bat will emit a series of sounds from its voice box, which echo back when they hit an insect (or anything else), thus allowing the bat to locate it.

The nose crest and impressive large satellite dish-esque ears evolved to make the bat extra proficient at picking up the sounds as they echo back in its direction. Beyond location, echolocation also lets the greater horseshoe bat know the size and shape of the object in front of it, meaning it knows if it wants to eat it. Moth – edible, brick wall – inedible.

The large ears and nose crest, as modelled beautifully here by our spear-nosed bat, act like dishes to pick up sounds echoing back from prey.

Trophy wall

Bats are overachievers and as a group claim many wildlife records. An obvious one is that they are the only mammals in the world capable of powered flight. There are other contenders, or should I say pretenders, to the flying mammal throne.

The vast majority come from Southeast Asia where being a small gravity-bound mammal appears to be a dangerous pastime. These mammals have accomplished gliding, or directional falling at a slow-pace, as it would be called if bats had written the textbook rather than humans.

The sugar glider wins Most Gorgeous Thing Ever although sadly the pet trade has cottoned on to this. I could write an enormous blog on why you should NOT own one in captivity. However, it is still just a furry glorified glider. The only other animals to have achieved powered flight are birds (crown group dinosaurs), and pterosaurs (not dinosaurs at all).

How many bats are there?

Having done my research for this blog I can tell you no one seems to know how many species of bat there are for certain and estimates range from 1,100 to 1,300. Whichever end of the scale it actually is, they still win the award for being the largest group of mammals in the world.

Bats make up around a fifth of the world’s mammal species. Some countries will have more non-bat-mammal species than 80% and others will have less, according to the habitats they have available.

However the UK is spot on with the world average. One in every five mammal species in the UK is a bat.

What is the smallest bat?

One of their number claims the title of smallest mammal in the world. The bumblebee bat just about reaches 3cm in total length and weighs only two grams. This means I put the equal weight of two bats in my tea every morning, which makes me think I should start using sweetener.

Incredibly, this entire species was unknown to science until it was first described and given a binomial name (Craseonycteris thonglongyai) in 1974.

It is only known to exist in 43 caves, split between Myanmar and Thailand, which means disturbance from over-excited wildlife tourists is a problem that local wildlife groups are having to constantly monitor.

Why do bats hang upside down?

Horseshoe bats are one of the few subspecies of bat that do hang upside down. Because a great horseshoe bat is so small – about the size of a small pear – it means they don’t get headrush when they spend time upside down.

By hanging upside down bats can get a good sense of what’s around them – using that echolocation we talked about earlier – and be quick to take flight.

Main image: Specht Fredrich, 1927.