Are Platypodes venomous?

Platypodes are one of the few mammals that are venomous, and the small amount of venom that can be injected through one of these spurs is potent enough to kill mammals many times their size. I was told by a friend who works in a zoo in Australia that their colleague was once spurred in the arm. It was so painful he was pleading with the doctors for his arm to be amputated!

During the mating season the amount of venom a male produces increases, which presumably means one of the main purposes of evolving such potent venom is to fend off rival males and get a girlfriend. In more anthropogenic cases, recent research suggests platypus venom could be used in a treatment for type 2 diabetes. For which they have frisky platypuses to thank I guess.

What does a platypus eat?

Platypuses are carnivorous and eat small water animals. This includes larvae, small fish and worms. They find it at the bottom of the water and store the food in their cheeks until they reach the surface and munch away.

Do platypus have teeth?

Platypuses don’t have teeth in the traditional sense. Their fossil ancestors had teeth but the modern platypus decided the sound of growing their own enamel was a reason for concern and produced coarse keratin pads instead.

A mouth full of hair sounds disgusting, and it only seems to work ‘fairly well’ to boot. According to a number of sources, platypuses will also scoop up coarse gravel to aid breaking down food in their mouths.

Platypuses are bottom feeders (legit term). This means animals that feed off of the bottom layer in aquatic environments. In the case of the platypus, it lives in rivers and uses the receptors in its bill to pick up the electrical signals given off by their prey. These are normally found in the form of insects, insect larvae, worms and shellfish.

How are platypus born?

Platypuses really don’t have teeth… I wasn’t lying before. However, platypuses are monotremes. This means they lay eggs, one of only two mammals to do so, the other being the echidna.

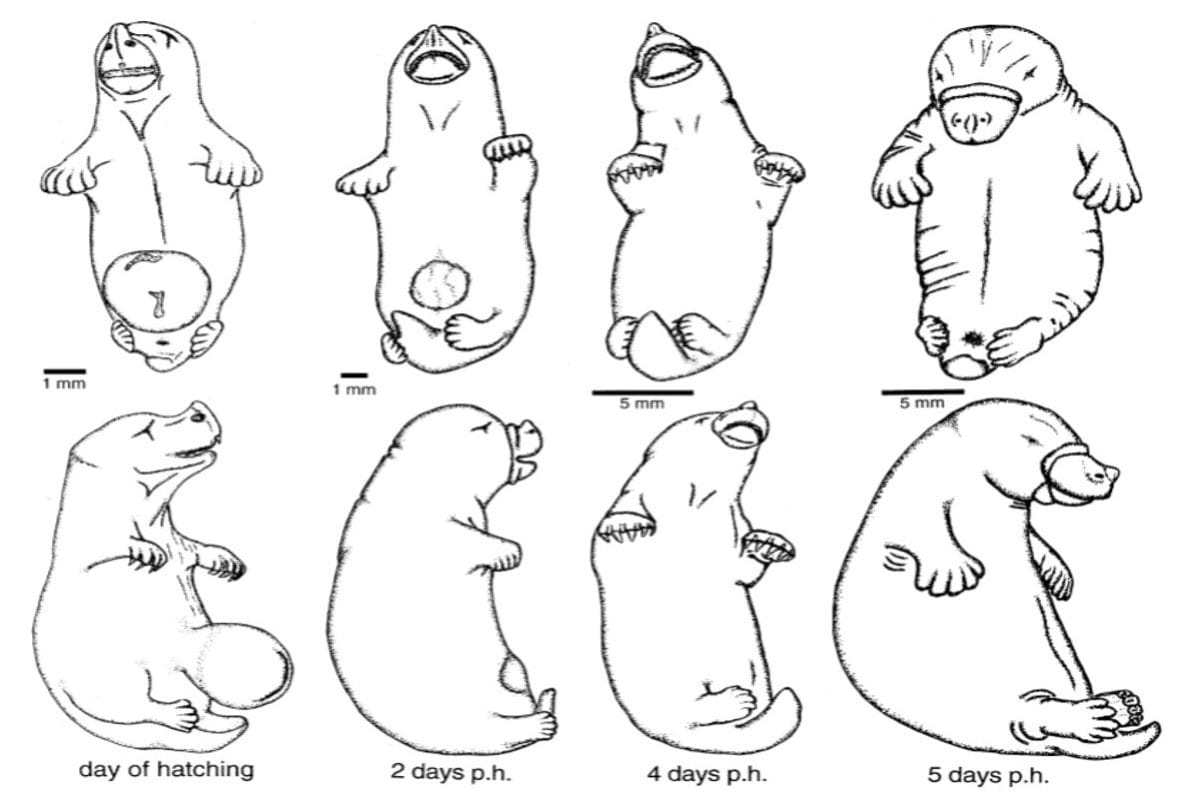

Similar to other egg-breaking babies – like those belonging to birds and many reptiles – the tiny egg-bound platypus has to break its way out of the egg.

For this, its ancestry provided it with an egg tooth on the top of its bill. This tooth is only a temporary facial addition that, once the baby platypus has broken free of its yolky home, will normally be shed within the next two days.

The egg tooth is not a real tooth as ours are, but a sharp, tooth-shaped structure made of keratin, around 0.3mm high. That may seem ridiculously small but a freshly hatched platypus is only around the size of a kidney bean so any larger and it would probably get neck ache.

Can platypus breathe underwater?

Platypuses are mammals and breathe air like humans. Like humans, they can hold their breathe to submerge themselves underwater. However, unlike humans, they are semi-aquatic animals and so they have some adaptations to help them. Platypuses have watertight nostrils and skin folders that cover their eyes and ears to keep water out when they’re diving underwater for food.

Our venomous piece of the past

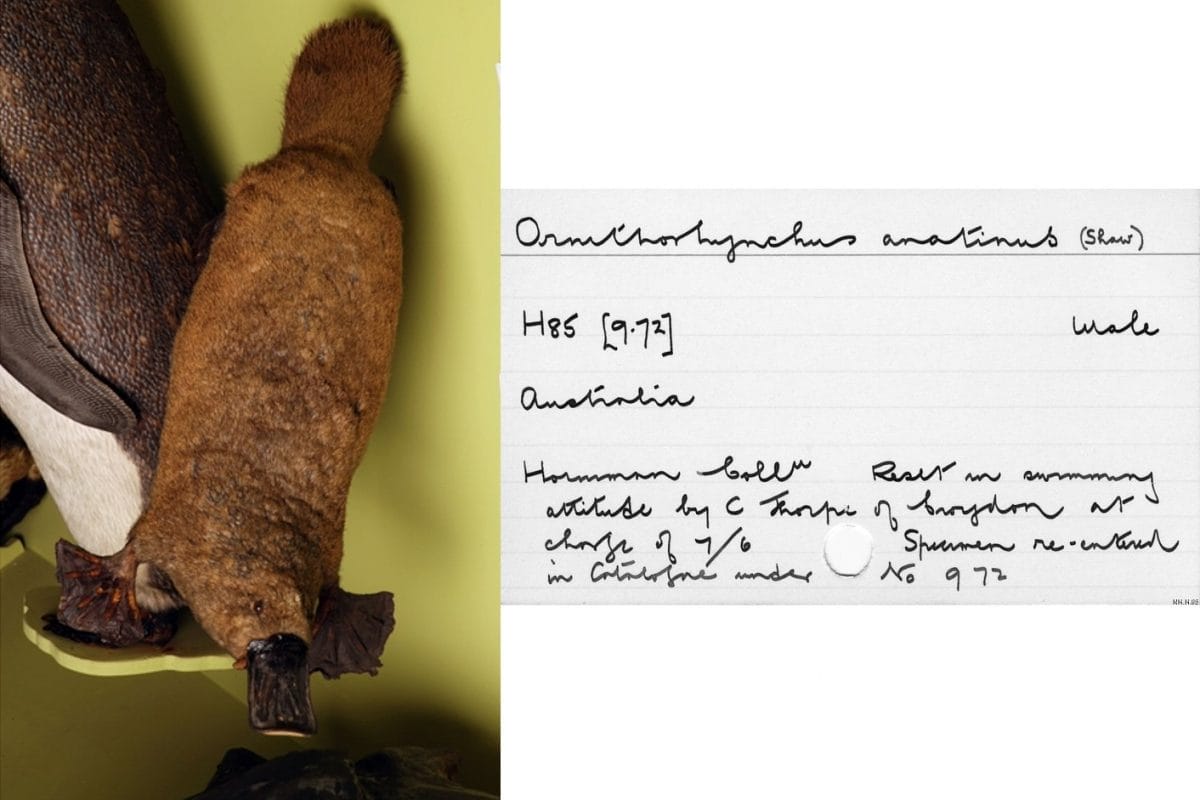

We have a number of platypuses in the collection, but one in particular is part of the original Frederick Horniman Collection.

That enigmatic accolade means it must have been acquired by our founder, and found prior to the Museum opening in 1906. So in modern speak, it’s well old.

We don’t know what the platypus looked like when it was first acquired by the Horniman. It could have been either a skin or a taxidermy mount.

Either way, at some time in the past the platypus was ‘re-set’ (the wording used on the record card), by the taxidermist Charles Thorpe, into the swimming position that you can see in the image below.

The price for this exquisite demonstration of skill was £0 d7 s6. For those who didn’t suffer through the confusing period of decimalisation, £0 d7 s6 means zero pounds, seven pennies, and six shillings. The value of that price today is around £10 (an exact figure is impossible to calculate on the basis we don’t know what year the work was carried out).

We know the specimen is a male as it has a sharp spike, called a spur, on the rear of each thigh.

Main image: Zoological Society of London