The declaration of war took place on 3 September 1939, but preparations for conflict with Germany started before this.

The Times newspaper ran an article on 25 August 1939 under the heading ‘Precautions in Crisis.’ This article set out rules for the screening of lights, darkening of windows and the meaning of various air raid warnings signals.

The piece advised that several London museums had been closed to enable the package and removal for the safeguarding of works considered to be national treasures.

The Horniman was closed on the outbreak of the war and the South London Advertiser of 19 January 1940 informed its readers that “several valuable museum pieces” from the Horniman had been “removed into safety areas several months ago”.

However, the expected aerial bombardment of London did not occur and when the Victoria and Albert Museum re-opened on 11 January 1940, there was a call for other museums to follow suit.

The Horniman re-opened on 4 March 1940 with two sections of the Museum being ‘available for inspection between 10am and 6pm each day’ except Sunday.

The building was restructured to house an air-raid shelter within the Museum, with space for 100 people and visitors were limited to this number.

A cutting from the Horniman Archives

The Horniman continued to run during the war, acquiring new items (which were mostly gifts), such as a large collection of sea shells, made by Sir William Hamer, and a Corbeille de Mariage, which is a type of wedding basket.

During this time, the Horniman was used for patriotic exhibitions such as ‘Russia Today‘ in December 1942, and a ‘United States Exhibition’ in August 1943, which featured photographs of American industries and buildings, including the huge circular granaries built for the storage of wartime harvests, as well as native costumes and maps of the States.

The latter exhibition drew many visitors, including large numbers of American servicemen.

Fundraisers were held, including an art exhibition in conjunction with the Royal Air Force ‘Wings for victory week’ in March 1943, which included an auction of artworks by local Civil Defence artists in what was the Lecture Theatre, which is now The Studio.

The Gardens were also called into service as the site of a barrage balloon and spotlight. The balloon was tethered to the ground by metal cables and was intended to keep enemy planes from flying too low on bombing raids. A local resident, recorded in the Forest Hill School Oral History Project No. 2, ‘South East London in the Second World War’ describes the balloons as being like ‘great big elephants’.

The South London newspapers reported flying bombs raids from June 1944 onwards.

These bombs had a limited range, so they had to be fired from the French and Dutch coasts. The bases were gradually overrun by the Allies following the D Day landings and the last attacks took place in October 1944. The heaviest period of bombing was referred to by the newspapers as ‘the Battle of South London’ and lasted from June to September 1944.

Lewisham was the third worst hit borough in London. It was hit by 115 flying bombs causing 275 casualties. 1,070 more were treated in hospital and 373 treated at First Aid Posts. A total of 1,129 houses were destroyed, 1,553 rendered uninhabitable, 5,305 seriously damaged and 55,335 suffered minor damage.

The Horniman was closed in August 1944 following damage caused by a flying bomb. The damage was not considered serious but the Council Architect reported in June 1945 that for the Museum building to re-open, the minimum work would entail:

- new main entrance doors;

- re-glazing and the repairing of lights in the Entrance Hall, Vestibule, Curator’s Room, Lecture Hall, Library and Library Stairs;

- repairs to the doors in the lecture Hall and Library, Mummy and Aquarium corridors; the removal of all defective plaster on ceilings; and

- flaking distemper on walls and ceilings.

In April 1945 the Education Officer, E.G. Savage, had started pressing for the re-opening of the Horniman as a matter of some urgency.

He stressed the importance of the Museum as an educational resource, and reminded the authorities of the extensive use of the Horniman by school children before its closure. The Education Officer estimated that following re-opening the Museum would be able to cater for at least 1,000 children a week.

Local people were also keen to see the Horniman open again.

In August 1946 an official who came to inspect the Horniman, was advised that applications were being received daily from the general public asking when the Museum would be available.

However, extensive damage countrywide, caused by the war, meant there were shortages of both materials and labour. Re-imbursement for the cost of the work could be claimed from the War Damages Commission, but consent for work to be carried out needed to be obtained from the Ministry of Health under the Defence (General) Requirements and licenses for timber obtained.

The work was due to start but had to be put off because priority was being given to de-bricking schools, and the work was only finally allowed to proceed after promises were made not to go to the local Employment exchange for labour.

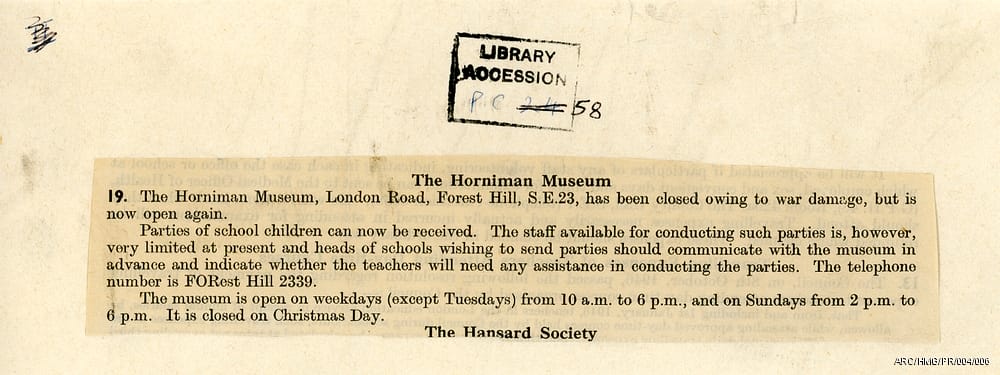

The Horniman re-opened on 25 September 1946 with the minimum possible repairs which made it safe for people to enter the building. The zoological and biological specimens had been repaired and reclassified.

The Aquarium was ready for new specimens to be collected, but the ethnological section was in a bad way with the staff being advised to just clean up the section and open it with a large notice stating that it was under re-arrangement. The West Hall (no longer there) did not re-open until April 1947.

In the Press Notice for the re-opening, the London County Council described the Horniman as a landmark of South London whose “many friends will be glad to know of its reopening” and “a magnet for generations of schoolboys.”