We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.

Dear reader

I do not claim to know all the facts.

What I do know is that the United Kingdom is not the authority example of a constitutional monarchy.

Circa 11th century, ages before the formation of the UK’s constitution, the Mossi kingdom in Africa had been a successfully established hierarchy of leadership, of primary resemblance to what we now see.

It is hard to admit that collectively we still see each other as ‘we and they’. And speaking of modern civilisation, African leadership, foundations, ancestry and tradition have provided a culture and lifestyle that society, as it exists today, is deeply indebted to.

I could talk about the tremendous disruption that executive and legislative powers Africa experienced; to the point that little trace of its precedent success is to be found.

I could even talk about, the transition from colonised to independent state, and the ongoing developmental challenges as a lack of internal cohesion and ethnic rivalries undermine the power of Africa’s governmental potential.

Instead, I would like to set the date; 1837.

As Britain enters its revered Victorian epoch, elegantly led by its queen, African leadership had already been pioneering its way to successfully repelling internal and external religious invasions, seen in the early example of the Nubia kingdom versus the Arabic, and even the Roman kingdoms.

Africa, reaping from a triple heritage identity, according to Mazrui (1986), nursing the birthplace of culture, institutions, moral codes, establishing the etiquette of eating, the ethics of mating and the rules of behaviour.

Europe, ruled by the constitution of the Magna Carta, and Roman, Dutch and French laws, try to transport its core principles into Africa, in retrospect, to service their own needs and not those of Africans, as many historians would retell. Being critical of the rule of law now means to collectively acknowledge the cultural blindness and Western imperialism complicity that perpetuates at its core.

Just like European kings and queens, Africa has a wealthy and dense history of leadership that is rarely mentioned, anywhere for that matter.

I certainly did not hear such names in my history or geography classes, as opposed to Winston Churchill and others.

During a time where the co-existence of regimes and governmental pluralism provided Africa with structural organisations that supplemented the livelihood of Africans in strength, diversity and continuum, I want to talk about the accounts we have to take into consideration that give African leaders their covert success. As the old saying goes, “no good deed goes unpunished.”

I would like you to know the instruments that made and make Africa such a prosperous and fruitful host of regimes and culture.

Pre-colonial Africa

Mekatilili Wa Menza (Kenya), a widow of age 53, fought against the establishment of the British colonial powers, and is hailed as a born hero by those who recognise her efforts.

Not your average freedom fighter, Wa Menza knew that she could not convince the men to fight the British easily, so she used the art of Kifudu dance to rally men and women to rise up against the external forces that were ravaging Kenya. The British wanted to take over the Giriama people, but it was thanks to Wa Menza that they never did, instead sparking a war between Nyere and Giriama.

Many would argue that Wa Menza is not celebrated enough. There is no road, no street, no important landmark is named after her.

Like Mekatilili Wa Menza, Queen Nzinga (Angola) fought in the trade wars of the Portuguese and Mbundu peoples of (what is now) Angola. The nature of these wars were not to overthrow the Portuguese, but to regain lost control of power in the areas of most interest – slaves, plantations, and markets.

By tradition, women were not restricted to specific roles. African women are versatile: mothers, cultivators, negotiators, central to the economy, and mythological beings.

Matrilineal succession and caste systems (which are not based on race or status but by inherited occupation) were the main aides in establishing such rulers, but also the virtues of each individual were evaluated and assessed in relation to what was expected of each ruler.

Speaking of tradition, a man who defied all rules of tradition and established a successful kingdom goes by the name of Oba (king or chief) Eware or Ewuare.

Oba Eware (Benin) ruled in the 1400s and is said to have been the ‘first’ king of Benin.

He was as ambitious as he was flawed, having destroyed much of the city on his ascension to power. He then instructed the re-building of structures and zones that took years to complete. The scarification process was refined by Eware to differentiate the citizens of the newly built city from the slave community.

He reformed political lineage procedures by redefining the succession to power trail to the first male-born son, and appointed an additional two-tier administrative chief system throughout his kingdom as a first.

Regardless of having primary control of duty, he personally led Benin’s army to successfully expand territory for (now) Benin over Edo lands. And to the benefit of African reputation, Eware is credited with developing mud, wood and ivory carving, as well as coral decorations and the creation of Bronze heads for the past Oba’s shrines.

On the extreme side of leadership, Lat Dior or Jor (Senegal) is spoken of as a villain by the powers he opposed – France. But he, like many pre-colonial heroes, fought against multiple threats to his reign; including Christianisation and Islamisation invaders, as well as the French colonial powers.

King of the Cayor state (in now Senegal), he died allegedly at the age of 44 but left a hell of a story to tell. Famous for his military and tactical practicality, the Thiédos (the military service to a Cayor king) were feared and revered at the same time, being the few who were able to defeat the French in battle.

Lastly for this period, I’ll speak of Yaa Asantewaa (Ghana).

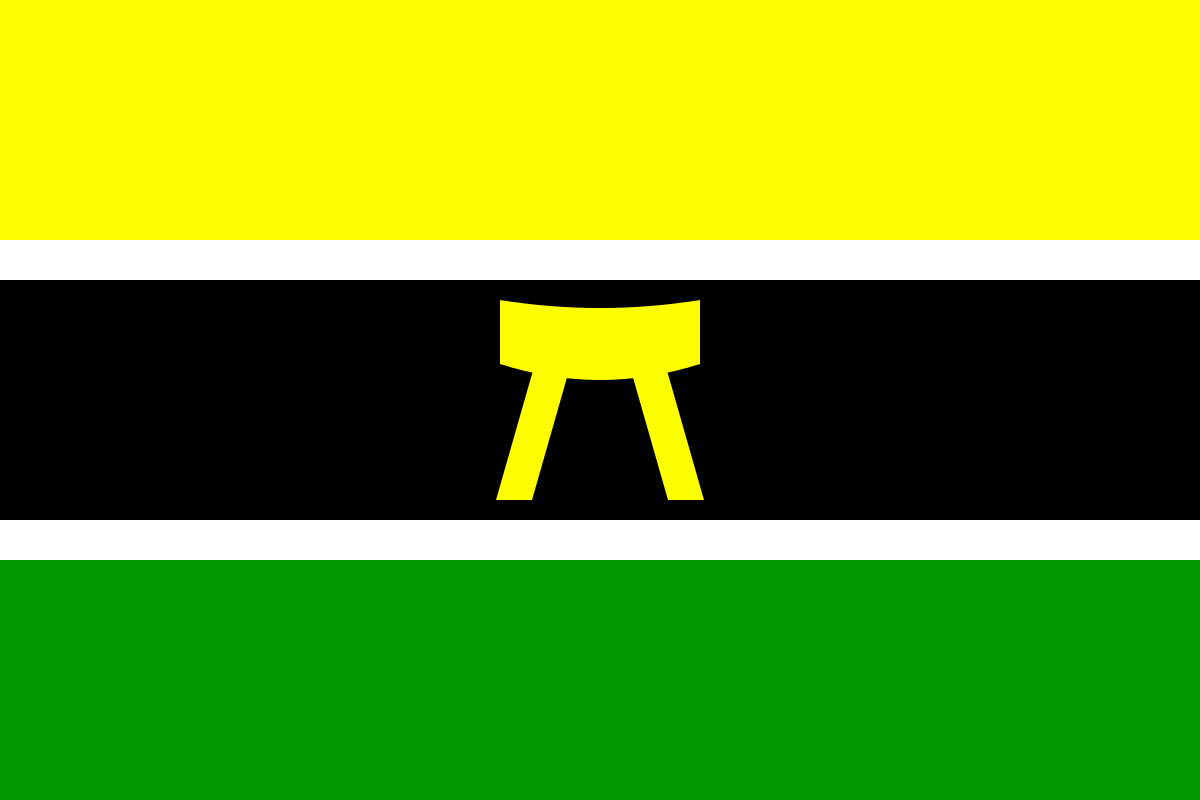

A farmer, mother and ruler, Asantewaa progressed to lead the Asante revolt against the British Empire in 1900, after the British governor of the Golden Coast demanded that the Golden Stool (the mystical material throne, symbol of the Ashanti ruler), be delivered to him.

This was the first example of a woman leading an army of 5,000 to war in Asante tradition. Unfortunately, during the war Yaa Asantewaa was captured and exiled to Seychelles. She died never knowing a free kingdom.

The role she played as a matriarchal figure leader to lead her peoples into battle is of significance as this was a foreign notion to British troops at the time. Admiringly, Asantewaa lives on in song and occasional regional and international commemorations.

Post-colonial Africa

African rulers have taken into account the ambiguity of one law for all, adapting to the subjective method of taking the individuals circumstances above all.

For example, in ancient West Africa, punishment for theft was:

- first offence, flogging and fine;

- second, mutilation;

- third, death.

But across smaller states of the kingdom, tribal chiefs established tribal courts in order to liaise with the accused and the accuser. In Southern Africa, a dispute would only reach an official court under special circumstances, given that there was no solvable resolution within the clan settings.

As Mutua (2016) would say, “A system governed by the rule of law is more likely to prevent the collapse of social and political order but… the medium of rights is not an adequate tool for human liberation.”

African laws and customs were not susceptible to huge changes that happen over time, as we see now in modern African society. There has always been a tradition or a word-of-mouth, spoken guidelines that people obeyed or followed that orientated the people’s collective consciousness, and the norm – in theory and practise – babies were taught from a young age and outsiders were labeled as such, so as to make everyone aware of the current social climate.

Some of the causes for change have been liberation movements of the people against the unfairly democratic states. Even though the Cayor constitution, the Songhai, the Yoruba, the Daoura, Ghana, etc. all followed strict and complex sets of traditional customs to ensure its kings were undisputed by nature and successful by practise, as we now see in Western culture, but do not experience in contemporary Africa – and colonialism.

The current extremely fluid state of the system of rule in Africa, after all, has been co-designed by the coloniser, and serves more purpose to the dominant party’s rule of economic and social activities –which to this day, after 500 years since the start and abolition of the transatlantic slave trade – is still the coloniser.

For arguments sake, imperialism never had absolute control over its dominions and vice-versa, there was no absolute subjection by the colonised, thus both sides can be seen as culpable in the assertion of power in Africa.

By no means did these African kingdoms reach perfection. As expressed by Anta Diop (1987) in Ghana, some members of pre-colonial dynasties were systematically massacred, but the monarchy itself was not extinguished. This gives evidence that there was never a lay republic, but a notion of most regimes being standardly democratic monarchies. But once collective life took precedence to individual life, it took to new levels of uncertainty.

African rulers in post-colonial times no longer held positions of prowess but occupy a status of composure and conformity.

It is thus a costly battle for Africans as the dehumanisation and corruption of ancient laws proves to split its states. After all, African societies and communities prosperously established systems and mechanisms that in Maine’s (1990) words, “what was to be to the family, so corresponded to the house and in sequence to the tribe and the state.”

With this in mind we are going to look at some revered examples of post-colonial leadership.

Thomas Sankara (Burkina Faso) was an adept of military strategy, who succeeded in rising to power of what was then Upper Volta, during the regime of Jean Batiste Ouédraogo (JBO).

This was in part, due to his charisma and honest and transparent oratorial style – his rallying speeches to those living in the extreme parameters of the current government, such as women, young adults and the impoverished. He even attempted to form alliances throughout Africa due to the shared colonial past histories.

When he became president, Sankara launched various initiatives for social and economic change. Sankara led the way by instilling nation-wide literacy plans, reforestation acts, deflating pay for civil servants and equalising the disparities in the public sector funds spending.

He lowered school fees and abolished certain taxes, redirecting funds to the maintenance of services, without the help of foreign aid. He fostered the women’s liberation movement by outlawing polygamy, forced marriages and genital mutilation. And like many African leaders, Sankara launched culture festivals to celebrate the indigenous nature of the country.

Though his legacy is complicated, ending with his assassination by an organised coupe d’état by a former friend, his acts and policies for the advancement and progress of Burkina Faso and Africa are still looked upon as influential and aspirational. It was only in 2019 that a statue of his person was erected in the capital.

A man who will forever live in infamy is Jonas Savimbi (Angola). A leader of the colonialism-opposing party of UNITA, Savimbi defended, very ambitiously, total independence from the colonial powers of the Portuguese that were still present, even after Angola gained independence.

It was his ideology, policies, military and diplomatic activities, as well as his charisma, that influenced the people to support him, believing that Angola as a country and Africa as a continent must become self-sufficient in order to experience freedom and progress.

Although a figure of committing many wrongs, including the decision to fight a civil war with the aid of foreign powers, issuing contradicting truths and the ordered killings inside his own party, he leaves an undeniable legacy of leadership potential and progressive ideas.

Digressing from military strategy diplomatics, this African leader is a Nobel Prize winner – Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf (Liberia).

Her accomplishments include nurturing the movement of woman rights, securing foreign investment for Liberia with the debt cleared in subsequent years, and introducing the Anti-Corruption Commission, with efforts to eradicate corruption in the country.

She fought against patriarchal forces that sought to oppose her presidency, who brought numerous claims and arguments as to why she should be removed from office. She succeeded in maintaining her post from 2006-2018.

Along with Johnson-Sirleaf stand a number of female presidents who get some to little recognition for the work they do in their respective countries, including Sylvie Kiningi (Burundi), Ivy Matsepe-Cassaburi (South Africa), Joyce Hilda Banda (Malawi) and Shale-Work Zewde (Ethiopia).

Standing in positions held largely by male-counterparts, the recognition of the cultural significance goes by overshadowed by the everyday politics of the patriarchal constitutions.

Lastly, is the recognition of Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal) as an African politician, intellectual and socialist. He advanced the sophistication of African people by distributing the term Négritude to combat the forms of assimilation of French customs and French colonial rule, impacting on how colonised peoples saw themselves.

By asserting cultural identity, Senghor fostered a political and artistic movement that drew influence from the Harlem Renaissance period, but with an assertion on traditional Africa. The essence of Négritude lay with the belief that Africa must devise methods of becoming traditionally aware and modernly recognised at the same time, drawing the lines on slave and colonial past, and cultural autonomy.

Senghor influenced many and his efforts have achieved recognition internationally and academically.

Evidence of existing monarchies in tribal life are not as clear as western social evolution, but we must not ignore the evidence for the success of African kings, queens, and leaders that aim to preside for, not over the plebes and the virtue of the African continent.

What is near is dear.

No discussion of Africa’s development is complete without an exploration of the continent’s relationship with the outside world.