History of Ginger

Today, we might take ginger for granted.

We usually get it out of the cupboard at celebrations such as Christmas and Thanksgiving, but it was once among the most popular and prized spices. Equally good sweet or savoury, hot or cold, dried or fresh, it was used as a medicine, confection, magical ingredient, condiment, flavouring, stimulant, nutraceutical, perfume and drink in antiquity, and still is today.

This tropical, fiery root was wonderfully named ‘the horned thing’ and ‘the antlered thing’ in ancient Sanskrit. Native to Oceanic Southeast Asia, although its precise origins remain a mystery, ginger was one of the first cargoes to travel the early global trade routes.

The simple map below shows some of the major land and sea trade routes in Roman times. Some ginger was brought overland, but most came via the sea. Prior to the Suez canal, the spices came up the Red Sea to Berenike, then overland to the Nile, and from there sailed into the Mediterranean, arriving in major ports such as Ostia at Rome as rare and expensive commodities.

The trade was originally in the hands of Arabic nations, but the Roman craving for spices drove Emperor Augustus to break this monopoly. He built a fleet of ships that opened up direct trade with India, and this also led to the conquest of Arabia in AD 109.

Today we think of spices primarily in culinary terms, but initially the Romans valued them for use in perfumes, cosmetics, incense, as preservatives, drugs, antidotes, love philtres and charms. Their heavy use in food came later, although the Romans were very fond of pickled ginger.

food box (box (food processing & storage)); scoop (food processing & storage); food samples

Anthropology

The lines between medicine and magic, and between food, drink and medicine were not as they are today.

The use of spices in medicine and magic came from the East where (some Romans wrote) the Magi used them as incense to invoke the gods, to cast spells, as antidotes to poison, to expel sickness, and to heal and protect through internal and external application.

Perfume was the other favourite use for spices in Imperial Rome. Statues of gods in temples were covered with perfumed oils and surrounded by incense burners, and perfume was considered an appropriate offering to the gods.

The elite, medicinal and religious use of ginger spread throughout the Roman Empire. Indeed, when the Empire fell some said this was due to decadence and a passion for spices and other luxuries!

With the demise of the Roman Empire, Arabic nations began to dominate the spice trade and develop the use of spices in food in the Middle East. By the time of the First Crusade (1096-1099) Europeans arriving in the Holy Land encountered an elaborate, highly spiced cuisine.

The taste for dishes flavoured with ginger, cinnamon, cloves, pepper, nutmeg, saffron, cardamom, coriander, cumin, turmeric, mace, anise and caraway was taken back to Europe, setting off a passion for spices that led to the Age of Exploration (15th-17th centuries).

Gingerbread In England

In England, one of the first mentions of ginger is medicinal, not culinary.

Found in the records of King Henry III’s apothecary in 1242-43, it was a kind of ginger conserve given to the king for medicinal reasons. Wine spiced with ginger – known as Hippocras was also considered medicinal and was drunk at the English court.

In the late Tudor and early Stuart periods, ginger and other spices were coming into England in increasing quantities. This is not to say it was easily available, there were no grocers and supermarkets as there are now. The guilds and traders controlled imports, and the elite procured their own supplies as did the master bakers.

Small quantities of spices could be obtained through apothecaries or at markets and fairs at great cost. For most ordinary people spice consumption was second hand, included in made-up products.

This was how ginger first appeared as a culinary luxury. Literally as ginger bread: spices mixed with breadcrumbs and wine. The old associations remained – this dish was considered to have medicinal or tonic qualities, an early nutraceutical. It was tasty but very crumbly, and was eaten with fingers – picked up like a sweetmeat – or with a spoon.

Two developments in the New World had a direct effect on English gingerbread.

The first was the increase in the supply of ginger itself. Around 1525, during its occupation of Jamaica, Spain introduced ginger to the island.

By 1547, the year of King Henry VIII’s death, 2,499,900 lbs of ginger was exported from Jamaica to Europe and England. There was a dip in production thereafter, but even so, the quantity of ginger coming into England rocketed.

The second factor was the growth of the Caribbean sugar industry, and the production of the dark sugar syrups treacle and molasses. Jamaica became a leading exporter of sugar under British colonial rule. This was due to the labour of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

These were a cheaper form of sweetener than dry sugar or honey, and gave gingerbread its distinctive dark colour and a deeper flavour.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, with sugar and ginger now relatively affordable and available, a mania broke out in Northern Europe and England for moulded gingerbread.

One particularly intriguing character of the day was Tiddy Dol, gingerbread seller extraordinaire. His nickname came from the gingerbread seller’s street cry, ‘Hot Spice Gingerbread, tiddy, tiddy dol’.

Tall, handsome and charming, one of the great London characters, he dressed like a gentleman in suits trimmed with gold lace, charmed the ladies, was always to be seen at the London fairs and the Lord Mayor’s parade, where he sold gingerbread which he claimed to make to a secret recipe.

The sketch above dates from 1806 and is titled, ‘Tiddy-doll, the great French-gingerbread-baker; drawing out a new batch of kings’. The figure of Tiddy Dol is transposed with a caricature of Napoleon as a ‘baker’ of new rulers, an imperialist who violates the sovereignty of his neighbours and destroys existing regimes.

Gingerbread Moulds

Moulding baked goods is an ancient technique. For a long time, some archaeologists dismissed moulds as merely decorative, but it is now realised that the designs on these moulds could be symbolic.

All symbols have meaning, but anthropologists see edible symbols as particularly significant. When eating symbolic food, something more important than simple feeding takes place. Some of the qualities or meanings of the food are transferred into the eater or drinker, as with the wine and wafer in Christian communion. By consuming secular symbols including foods that commemorate particular events like weddings or coronations, the eater can become one with these great events.

Gingerbread moulds were highly varied; there are examples of religious moulds, moulds of kings and queens, others that represent battles, soldiers, particular towns and places, those that celebrate weddings and funerals, mark coronations, record local costumes, occupations, unusual events and much more.

In this way, the gingerbread mould reflected current affairs, and has been appropriately described as an ‘edible mass medium’.

The Horniman has a wonderful collection of gingerbread moulds.

One particularly interesting mould (below) is an example from the Netherlands with a maritime theme. The many ship moulds that survive show how much the world of the period was a maritime one, both in terms of trade and war.

gingerbread moulds (moulds (food processing & storage))

Anthropology

Similarly, military moulds are one of the largest categories of moulds that have come down to us today.

They remind us how unsettled the 17th and 18th centuries were in Europe and later in the Americas. On the reverse of the same mould, a soldier is depicted trampling over houses and wreaking destruction.

Another sinister mould that was commonplace was a death figure. Made for funerals, it depicted Death as driving a carriage or a hearse.

gingerbread mould (mould (food processing & storage))

Anthropology

Windmills and Dutch motifs became particularly popular after the accession to the English throne of William of Orange in 1689, and Dutch gingerbread was considered to be very good, as it still is today.

gingerbread mould (mould (food processing & storage))

Anthropology

Not all moulds were made of wood; some were ceramic such as this example from Switzerland.

This mould symbolises the Lamb of God and was popular at Easter.

Ceramic moulds have not survived as well as wooden ones because they are not decorative; the other side looks only like a lump of clay. These were all too easily thrown out or discarded in a domestic setting.

mould (food processing & storage)

Anthropology

Gingerbread Mould Impressions and Biscuits

The Horniman collection includes a number of edible and inedible mould impressions.

A spectacular gingerbread example from Poland (below) depicts a woman spinning. It depicts details of costume, furniture and the importance of spinning before the days of mass manufacture.

This biscuit was traditionally given as a gift at Christmas.

Another fascinating biscuit commemorates a specific place and two unusual people, the so-called Biddenden Maids.

According to tradition, Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst were twins conjoined at hip and shoulder. Born in Biddenden, Kent in about 1100, they lived for some 34 years. Following their death, they left lands that funded an annual dole of bread and cheese to the poor in the area at Easter, which later became the gift of a moulded gingerbread.

Today, the biscuits are still given out at Easter to eligible Biddenden residents and are also sold as souvenirs to tourists.

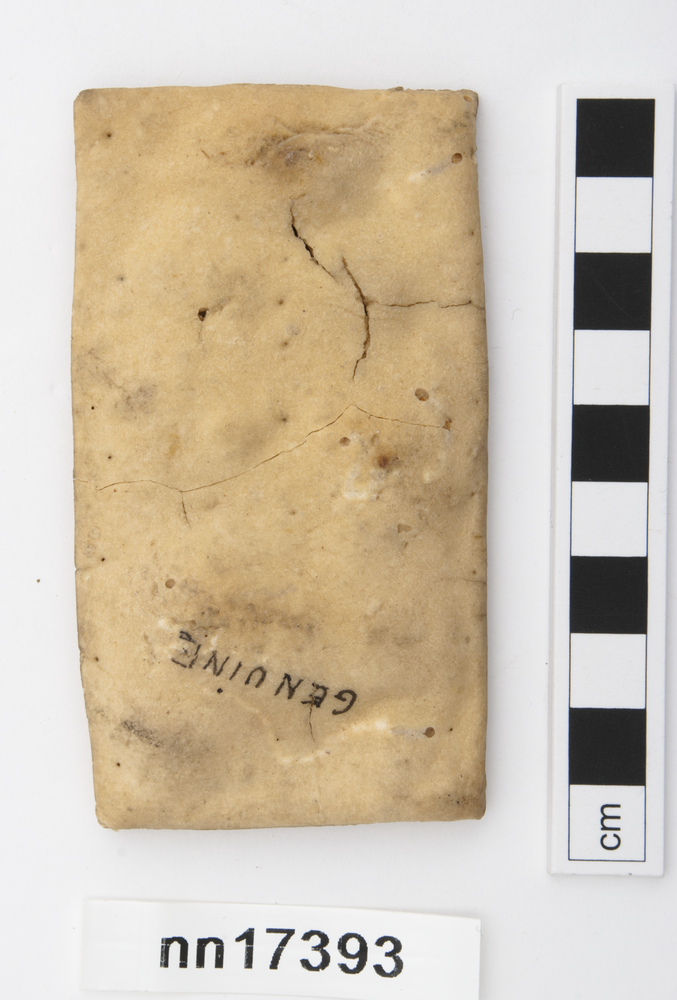

The Horniman has two Biddenden biscuits 21.8.57/24 (above) and 21.8.57/25 (below). The former is inscribed as being the genuine article and the latter as an ‘imitation’.

This suggests an important distinction made between those given to the local residents and those sold as facsimiles to tourists.

Museums have also made clay impressions to demonstrate in more detail the mould designs, just as the two swans below – as these birds mate for life, these biscuits were a popular love token.

gingerbread mould (mould (food processing & storage))

Anthropology

Gingerbread: the Victorian Era

With ginger and other spices becoming more accessible during the Victorian period, these luxuries began to trickle down the social scale. Guilds, monasteries and master bakers no longer had a monopoly. Moulded biscuits were now made by small producers, for a wider public.

During this time biscuits got smaller, and their imagery less elaborate – tending to show everyday occupations like the popular milkmaid, jesters, or fairground figures, like Mr Punch.

gingerbread moulds (moulds (food processing & storage))

Anthropology

One could even make decorated gingerbread more easily at home as demonstrated by this ornate roller from the Horniman collection.

You could make a sheet of twelve different patterned biscuits from this roller.

The Victorian period was the heyday of gingerbread biscuits, cakes and breads in Britain.

There were gingerbreads flavoured with orange, almonds and coconut, using different spice combinations. Regional variants also emerged – like Whitby gingerbread, and the famous Grassmere gingerbread, made with oatmeal or whole wheat flour. There were regional ginger biscuits too, like the Cornish fairings and the ginger nuts sold at Dawlish.

The increase in consumption of cakes and biscuits (or sweet baked goods) was intertwined with the growth in popularity of tea as a drink and tea parties as part of the Temperance movement. Britain’s tea was originally imported from China and the taxes on tea helped to fund the expansion of the British Empire. Tea was the source of the Horniman family’s wealth.

Gingerbread was just as popular in America during this time, where national differences soon arose. American gingerbread is more of a cake than bread, always very dark and made with pure treacle or molasses, not treacle mixed with honey or golden syrup, as in England.

In American food history, gingerbread is associated with the early days of the nation when the colonies broke away from Britain, and as such is considered quintessentially American. Every Christmas, a large gingerbread cake is baked and put on display at the White House, to celebrate this ‘American-ness’.

Really elaborate moulds are now a thing of the past, but the cookie cutters that replaced them still come out at Christmas, as do many of the scents and flavours of the early gingerbreads, and things like mulled wine – the descendant of hippocras, along with festive room scents like those used in ancient Rome.

Edible symbols and decorated gingerbread are still with us, so I hope you will be inspired by the story of ginger and the objects in the Horniman collection to bake some gingerbread, ginger cake or ginger biscuits yourself.